Mylan, Valeant Go to War Over Katten Disqualification

Valeant's attempt to disqualify a team of Katten Muchin Rosenman patent litigators led to a showdown Wednesday at the Federal Circuit.

September 13, 2018 at 12:10 PM

10 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

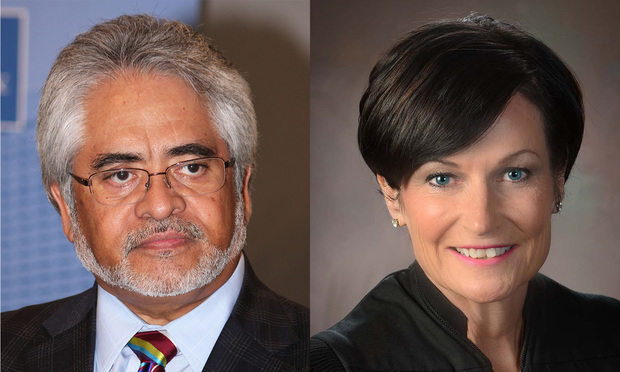

Jimmie V. Reyna (left) and Kathleen O'Malley, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

Jimmie V. Reyna (left) and Kathleen O'Malley, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

It all started pleasantly enough.

Katten Muchin Rosenman announced it had hired partner Deepro Mukerjee and eventually four other patent attorneys from Alston & Bird in April. The firm told the New York Law Journal the new team was expected “to generate significant revenue for the firm in the pharmaceutical space.”

Mukerjee was on the verge of going to trial for Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. in New Jersey. He notified Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner partner Justin Hasford, who represents opponent Valeant Pharmaceuticals International Inc., about his move the day it became official.

“Mr. Hasford left me an equally cordial and gracious message wishing me the best and acknowledging that it sounded like our work relationship would not be changing,” Mukerjee stated in a declaration.

Read the Key Documents:

Things have become less friendly since then. It turns out Katten Muchin does regular work for Valeant subsidiary Bausch & Lomb. Within a few weeks, Valeant was accusing Katten of divided loyalties and demanded it withdraw from both the New Jersey case and separate Mylan litigation against two other Valeant subsidiaries.

All three cases are now on appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The D.C.-based court put them on hold for an hour of arguments Wednesday over Valeant's motions to disqualify.

Finnegan partner Charles Lipsey argued that Valeant and Bausch share the same in-house legal department. By bringing in Mukerjee's team, Katten created a situation where “on Day One that legal department will have to see the law firm as giving advice, and on Day Two will have to see that law firm as an adversary pounding their head. “

Katten partner Michael Verde argued Bausch & Lomb is a stand-alone company his firm has represented since 2001—long before Valeant acquired it in 2013. And Valeant's engagement letter permits outside law firms that bill less $1 million a year to be adverse to affiliates like Bausch, he contended.

That November 2016 engagement letter, signed by Valeant assistant general counsel Denis Polyn and Katten relationship partner Floyd Mandell, is key to the fight. Valeant's outside counsel guidelines are incorporated into the letter by reference.

The guidelines state they govern the relationship between Valeant, “its subsidiaries and affiliates,” and outside counsel. The guidelines also require “a significant degree of loyalty from Valeant's key external firms,” which are defined as those billing more than $1 million per year.

Valeant states in court filings that it has paid Katten at least $4.3 million for IP legal services over the last seven years.

Verde argued Wednesday that the converse of that provision is that a firm like Katten, which “never came close” to billing $1 million, is free to take positions adverse to affiliates, so long as the firm remains within the ABA rules of ethical conduct.

The judges sounded more skeptical of Katten and Verde.

“How can you not see it as a conflict?” asked Judge Jimmie Reyna. “You sign an agreement with Valeant. You're getting your bills from Valeant. Valeant provides the in-house counsel relationships that your firm is dealing with.”

“We don't see a conflict, because there's nothing in here which we're actually doing work for Valeant Pharmaceuticals International,” Verde replied.

Mukerjee's jump to Katten Muchin was more than six months in the making. Negotiations began in September 2017. At Alston & Bird, Mukerjee worked “almost exclusively” for Mylan and its affiliates, comprising some 40 representations since 2009, according to his declaration. Most involve disputes over Abbreviated New Drug Applications, such as the New Jersey case against Valeant. Mukerjee also was litigating a West Virginia action against Valeant subsidiary Salix Pharmaceuticals Inc. and a Patent Office validity challenge stemming from that case.

Mukerjee was informed during the hiring process that Katten represents Bausch & Lomb. He believed he had no conflict because he had not been adverse to Bausch since 2016, according to his declaration.

Mukerjee officially joined Katten on April 17. Partners Lance Soderstrom, Jitty Malik and two associates followed within a few weeks.

The first sign of trouble came May 10. Robert Gorman, vice president for intellectual property at Valeant, emailed Katten relationship partner Mandell to say he was “stunned to learn” Katten made the hires, given that “Valeant has entrusted Katten with many significant intellectual property cases … for decades.”

“I trust you can understand that I have many questions,” he wrote. They included how Katten's standard conflicts check for new hires works, how it didn't uncover the conflict of interest and why Valeant wasn't notified in advance.

“This seems to me to be a clear breach of loyalty to Valeant,” Gorman wrote, “and I need to ask with all respect, for Katten to withdraw from representing Mylan in the lawsuits.”

Verde, who acts as Katten's general counsel, replied the next day. “There seems to be a fundamental misunderstanding regarding the scope of Katten's work for Valeant,” he wrote. “Almost all” of the Katten work since 2015 had been for Bausch & Lomb and another Valeant subsidiary, Obagi Cosmeceuticals. “While you treat these independent companies as if they were Valeant, your Outside Counsel Guidelines say otherwise.”

Under those guidelines, “Katten has never been a 'key external firm' and so, consistent [with] both your Guidelines and Rule 1.7 of the [ABA] Rules of Professional Conduct, Katten properly considered Bausch & Lomb and Obagi as separate companies for conflicts purposes,” Verde wrote.

“As for your other questions,” Verde added, “we do extensive conflict checks as part of our hiring process and were well aware of this situation months ago but, for the reasons set forth above, did not deem this to be a conflict that would prevent Mr. Mukerjee and his team from handling a trial that was more than two years in the making.”

Any disqualification motion would be a “meritless tactical maneuver,” Verde said in a separate letter to Valeant counsel at Finnegan.

Valeant and Salix sprung that maneuver in May. By then, the New Jersey case had ended in summary judgment and was on its way to the Federal Circuit. The West Virginia cases were fully briefed at the appellate court and set for argument in July. All three appeals were postponed, pending the hearing on Valeant's disqualification motions.

Both sides argued Wednesday to the Federal Circuit that the engagement letter and outside counsel guidelines should control.

“Clearly a corporate affiliate must be treated as a client … if the lawyer has agreed to so treat it,” Finnegan's Lipsey said. It doesn't matter “whether any actual work has been or is to be performed for the affiliate.”

Bausch & Lomb isn't just any subsidiary—its sales represent 57 percent of Valeant's revenues, Lipsey said. Salix generates 20 percent. Valeant demands that they and all other affiliates be treated the same as the parent because they share the same administrative work, computer systems “and most importantly share a common legal department.”

But, asked Judge Reyna, what about the “key external firms” provision? It “seems to me to say that if you're not a key firm, then it's OK to represent affiliates.”

Lipsey said that provision is actually intended to expand the duty of loyalty beyond ethical conflicts of interest to business conflicts of interest, such as representing direct competitors in unrelated litigation or transactions. Katten's interpretation is nothing more than “an effort to justify a headlong dash into the arms of a more lucrative client.”

“So what is the harm to Valeant or any of its affiliates?” asked Judge Kathleen O'Malley.

It's the risk of “confidential information contamination,” Lipsey said, including Valeant's overall approach to risk assessment and settlement. “These ANDA cases are often mating dances headed for settlement,” he said.

When it was his turn, Verde stressed that Katten only done trademark and advertising law for Bausch & Lomb.

“Well, it doesn't matter that you're doing one kind of work for one entity and another kind of work for another, if in fact there is coverage under the [engagement] letter that says you can't represent affiliates,” O'Malley said. “You could be doing employment law for them, and it wouldn't matter.”

“Absolutely, your honor,” Verde agreed. “It's a contractual matter and why this letter is so centrally important.”

Verde said such guidelines have become increasingly common among bigger clients. But these guidelines don't sweep as broadly, he argued. “We were never a key external firm, never came close to being a key external firm, and that was an important consideration for us.”

“Isn't it in the law firm's best interest,” O'Malley asked, “where there's any question, to get an affirmative letter that says, 'We are not barred from representing any of your affiliates'?”

Easier said than done, Verde suggested. “We didn't negotiate it,” he said. “Valeant imposed it upon us.”

Why not seek a conflict waiver? Reyna asked.

“We didn't see it as a conflict, so we didn't seek a waiver,” Verde said. “It's a very dangerous thing, practically speaking, if you don't believe there's a conflict, to ask for a waiver. Because then the client says 'no,' and you still think there's no conflict. You're basically handcuffed by that.”

O'Malley kept pressing Verde about why Katten didn't seek clarification.

“This was the letter we were given,” he said. “These are not negotiable documents.”

Judge Alan Lourie ended the hourlong hearing with a dash of humor. “We've heard valiant arguments from both sides,” he said, “and we'll take the motions under advisement.”

Read more:

Former Dickstein Shapiro Lawyers Sue Blank Rome Seeking $4 Million in Unreturned Capital

Gibson Dunn's Ted Olson Registers as Foreign Agent for Saudi Arabia

Harvard, MIT Win Appeal in Battle Over Gene Editing Patents

Pershing Square, Valeant Agree to $290M Settlement Over Allergan Insider Trading Allegations

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Litigators of the (Past) Week: Defending Against a $290M Claim and Scoring a $116M Win in Drug Patent Fight

Litigators of the Week: A Trade Secret Win at the ITC for Viking Over Promising Potential Liver Drug

Litigation Leaders: Mark Jones of Nelson Mullins on Helping Clients Assemble ‘Dream Teams’

Litigators of the Week: An Early Knockout Win in the Decongestant MDL

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250