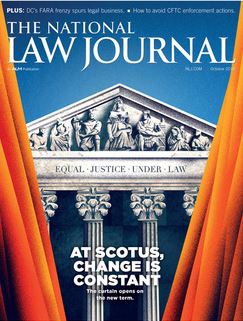

At the U.S. Supreme Court, Change Looms

The curtain opens today on the new term. But the full U.S. Senate has yet to vote on Justice Kennedy's would-be successor, Judge Brett Kavanaugh.

October 01, 2018 at 12:06 PM

7 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

For the second time in three terms, the U.S. Supreme Court opens a new session without a longtime crucial voice or vote, and with the uncertainty that brings for its agenda and the nation.

This term, Justice Anthony Kennedy, the high court's sometimes unpredictable center and critical fifth vote, is absent. His retirement after 30 years on the court took effect in July. As of October 1, the first day of the new term, the full U.S. Senate hasn't yet voted on his would-be successor, Judge Brett Kavanaugh, who had a contentious hearing over sexual assault allegations last week. At President Trump's request, the FBI is undertaking a supplemental investigation into Kavanaugh's background that is slated to be completed in the coming days. Kavanaugh is by all accounts more conservative than the justice for whom he clerked. His confirmation could have major ramifications for a host of political-social issues, ranging from the death penalty to abortion to presidential power.

The October 2018 term is the latest iteration in the Roberts court's mantle of change. Prior to John Roberts Jr. taking his place as chief justice in 2005, the faces on the bench had gone unchanged for 11 years—the longest period in modern times. In little more than that same period, the court, assuming the confirmation of Kavanaugh, will have experienced six new justices.

In the October 2016 term, the often caustic, often humorous voice of Justice Antonin Scalia was missed following his sudden death in February of that year. Scalia, a reliable member of the court's conservative majority, was of course succeeded in 2017 by Justice Neil Gorsuch, another reliable conservative.

➤➤ For more on what the U.S. Supreme Court is considering this term—and predictions by our veteran SCOTUS reporters Marcia Coyle and Tony Mauro—see our story, “Six Cases to Watch This Term.”

The October 2018 term lacks, at least for now, the blockbuster potential that marked what Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg described as the “more divisive than usual” term that ended in June. But history teaches that situation may change dramatically with the addition of just one or two cases to the docket. And the lack of blockbusters doesn't mean a lack of important challenges.

Businesses, consumers, workers and others will be watching closely as the justices take up issues involving age discrimination in employment, the Endangered Species Act, securities fraud, arbitration, cy pres settlements, antitrust damages, patents and copyrights, among others.

Even if the new term's final docket falls short of hot-button issues, the potential for another highly divisive term looms. Moving toward the high court are cases involving the Trump administration's effort to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program for so-called “Dreamers,” the administration's ban on transgender persons in the military, alleged emoluments clause violations by President Donald Trump, a citizenship question on the coming census and more.

Adding to uncertainty for the court is the current political situation. What legal questions may arise from the special counsel investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 elections? Some questions already being discussed include: Can a president be subpoenaed to testify before a grand jury? Can a president be indicted?

Those questions dominated questioning of Kavanaugh by Senate Democrats during the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearing in September. Although the judge played an active role in the independent counsel investigation of President Bill Clinton in the 1990s, he later wrote that he believed presidents should not be the subject of civil or criminal investigations while still in office because such investigations detract from the important work of the presidency. He suggested it was Congress' role to act on any serious malfeasance.

Kavanaugh also insisted that he had an open mind on whether a sitting president could be subpoenaed to testify or indicted. He noted that the U.S. Department of Justice has had a policy opinion for years stating that a sitting president may not be indicted. However, after being repeatedly pressed on the scope of presidential power, Kavanaugh stated, “A court order that requires a president to do something or prohibits a president from doing something is the final word in our constitutional system.”

The “story” of the October 2018 term is likely to be the impact of the court's newest justices. Will the conservative majority without Kennedy be muscular and aggressive, turning harder to the right than it has in the last dozen years? Will Roberts, if not the center of the court like Kennedy was, be a moderating force in certain areas of the law?

Six key cases in which the justices already have agreed to hear arguments are capsulized following this article. Here are a few more to watch:

Age Discrimination

The federal Age Discrimination in Employment Act applies to private employers who have a minimum of 20 employees. But does that minimum requirement also apply to political divisions of a state, or to all state political subdivisions of any size? The U.S. Justice Department, as an amicus party, argues the ADEA applies to political subdivisions of any size. Mount Lemmon Fire District v. Guido.

Death Penalty

Alabama has twice sought to execute Vernon Madison who has been on death row for more than 30 years and has vascular dementia. Does the Eighth Amendment allow a state to execute a prisoner whose mental disability leaves him with no memory of the capital offense that he committed or understanding of his scheduled execution? Madison v. Alabama.

First Amendment

Two Alaska state troopers arrested Russell Bartlett for disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. After charges were dismissed, Bartlett sued the troopers for false arrest, excessive force and other counts. The justices will decide whether the existence of probable cause defeats a First Amendment retaliatory arrest claim. Nieves v. Bartlett.

Pre-emption

Merck submitted data to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration suggesting that its Fosamax drug may be associated with certain bone fractures and proposing a warning to address the risk. The FDA ultimately rejected the proposed warning about stress fractures, stating it was not supported by the data. Merck was sued by consumers who suffered severe atypical femoral fractures from taking Fosamax. Merck asks whether their state failure-to-warn claims are pre-empted by the FDA's rejection of its proposed warning of the less serious stress fractures. Merck Sharp & Dohme v. Albrecht.

The justices on Sept. 24 held their “long conference” in which they sorted through more than a thousand petitions that had been filed over the summer and chose which cases to hear. They will continue to add new cases to the docket until about mid-January.

Editor's Note: This cover story was updated from the version that appears in our October 2018 print magazine to reflect the latest news involving U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Litigators of the Week: A Knockout Blow to Latest FCC Net Neutrality Rules After ‘Loper Bright’

An ‘Indiana Jones Moment’: Mayer Brown’s John Nadolenco and Kelly Kramer on the 10-Year Legal Saga of the Bahia Emerald

Litigators of the Week: A Win for Homeless Veterans On the VA's West LA Campus

'The Most Peculiar Federal Court in the Country' Comes to Berkeley Law

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250