Daily Dicta: Paul Weiss Wins Rare Delaware Decision Allowing Client to Kill $4.8B Merger

Delaware courts don't normally look kindly on companies that try to pull out of billion-dollar merger agreements. But this case was "markedly different."

October 03, 2018 at 12:45 PM

10 minute read

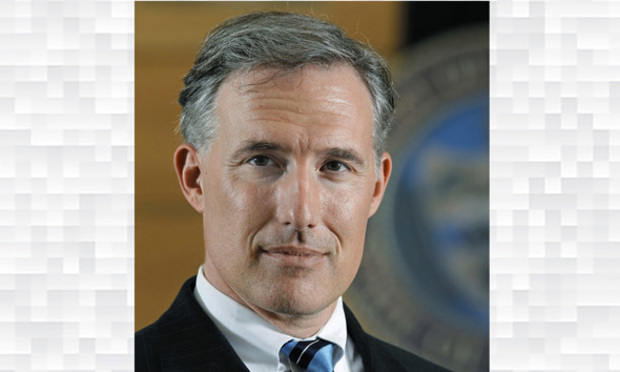

Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster of the Chancery Court of the State of Delaware. HANDOUT.

Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster of the Chancery Court of the State of Delaware. HANDOUT.

Delaware courts don't normally look kindly on companies that try to pull out of merger agreements. Buyer's remorse is for when you spend too much on a pair of shoes that hurt your feet—it's not a reason to bail out on a multi-billion-dollar deal.

But this case was different. A team from Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison won an unusual victory in the Court of Chancery on Monday, when Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster (pictured above) ruled that German healthcare giant Fresenius SE & Co. could cancel its $4.75 billion agreement to acquire Illinois-based Akorn, Inc., a specialty generic pharmaceuticals company.

It was a clash of legal titans, with Paul Weiss litigation partners Lewis Clayton, Susanna Buergel, Andrew Gordon, Moses Silverman and Stephen Lamb facing off against Cravath, Swaine & Moore's Robert Baron, Daniel Slifkin and Michael Paskin for Akorn.

The case went to trial over five days in July, and the judge went out of his way to praise both sides for their conduct.

“The parties prepared for trial during eleven weeks of highly expedited litigation,” Laster wrote in his 247-page opinion. “Despite the massive effort this entailed, the parties required assistance with only one significant discovery dispute, which involved contentious privilege issues. This case exemplifies how professionals can simultaneously advocate for their clients while cooperating as officers of the court.”

Fresenius agreed to buy Akorn on April 24, 2017. In a press release, the company said Akorn, which specializes in making injectables, eye drops, oral liquids, inhalants and nasal sprays, would add “expertise in development, manufacturing and marketing of alternate dosage forms, as well as access to new customer segments like retail, ophthalmology and veterinary practices.”

Fresenius agreed to buy Akorn on April 24, 2017. In a press release, the company said Akorn, which specializes in making injectables, eye drops, oral liquids, inhalants and nasal sprays, would add “expertise in development, manufacturing and marketing of alternate dosage forms, as well as access to new customer segments like retail, ophthalmology and veterinary practices.”

But shortly after Akorn's stockholders approved the merger, Akorn released its second quarter results. Despite earlier rosy projections, Akorn's reported revenue dropped 29 percent year-over-year. Operating income was down 84 percent, and Akorn's reported earnings of $0.02 per share represented a year-over-year decline of 96 percent.

The company blamed unexpected new market entrants and the unforeseen loss of a key contract.

Suffice to say, Fresenius leaders were not pleased.

CEO Stephan Sturm “could not understand how the parties had signed up a deal, only to have Akorn's results fall 'off the cliff,'” Laster wrote. He “asked his executive team whether they thought Fresenius 'had been defrauded.' They did not think so. Sturm 'also asked if there was a way to cancel the deal.' His team said 'not at this point.'”

Laster continued, “Although Akorn has asserted that Fresenius decided at this point to find a way to terminate the deal, I do not agree. Sturm testified credibly that he wanted 'to get myself knowledgeable about my options under the merger agreement, but also my responsibility, my fiduciary duties in serving my shareholders, and hence I was asking my colleagues on the legal side to get us appropriate legal advice.'”

That's when Fresenius hired Paul Weiss, according to Laster. (Allen & Overy did the deal work.) In-house lawyers looked into other deals gone bad, and found Abbott Laboratories' attempt in 2017 to terminate its acquisition of Alere Inc., which was represented by Paul Weiss. The deal went through, but at a lower price.

Meanwhile, Akorn continued to flail. Its third quarter results were even worse than its second quarter, and it had to push back the launch dates of multiple new products. The ones it did manage to launch netted a mere $3.3 million in sales, versus projections of $60 million. One Fresenius executive called the results “almost comical.”

“These guys are shameless,” Sturm wrote in an email. “I'm afraid we've got to build our legal case.”

Akorn lawyers argued this meant the CEO intended to manufacture legal grounds to get out of the deal, but Laster didn't see it that way. Sturm “no longer liked the deal, and he would seek to terminate it if Akorn's performance continued to deteriorate, but Fresenius also would live up to its obligations,” the judge wrote.

Plus there was no easy way out. Yes, Akorn was doing terribly, but that wasn't necessarily the same as a material adverse effect that would justify killing the deal. “Based on advice from Paul Weiss, Fresenius concluded that it did not have clear grounds for termination. Given the Delaware precedent, this was hardly surprising,” Laster wrote.

In prior cases, he noted “this court has correctly criticized buyers who agreed to acquisitions, only to have second thoughts after cyclical trends or industrywide effects negatively impacted their own businesses, and who then filed litigation in an effort to escape their agreements without consulting with the sellers. This case is markedly different.”

The game changed last fall, when Fresenius received anonymous letters from a whistleblower who detailed flaws in Akorn's quality control processes and the accuracy of its representations regarding its regulatory compliance.

Determined to close the deal, Akorn was not eager to look into the allegations.

“Akorn decided not to conduct its own investigation into the whistleblower letters because Akorn did not want to uncover anything that would jeopardize the merger,” Laster wrote. “Akorn chose to rely on its deal counsel, Cravath, Swaine & Moore. Cravath's job was not to conduct an investigation, but rather to monitor Fresenius's investigation and head off any problems.”

Fresenius, by contrast, conducted a real investigation, hiring a team from Sidley Austin led by Nathan Sheers, who specializes in FDA enforcement and compliance.

The problems that eventually came to light were bad.

Really bad.

One consultant testified that some of Akorn's data integrity failures “were so fundamental that he would not even expect to see them 'at a company that made Styrofoam cups,' let alone a pharmaceutical company manufacturing sterile injectable drugs,” Laster wrote. “He believed that the 'FDA would get extremely upset' about Akorn's lack of data integrity 'because this literally calls into question every released product [Akorn has] done for however many years it's been this way.'”

For example, any Akorn employee could add, delete, or modify electronic data, which undermined all of the test and production data—and indeed, investigators found evidence of data fabrication by at least four people.

Investigators also found Akorn submitted at least three applications to the FDA for approval to make generic drugs “based on false or misleading data,” Laster wrote.

On April 22, 2018, Fresenius gave notice that it was terminating the merger agreement.

On Monday, Laster gave them his blessing to walk away.

“Akorn's dramatic downturn in performance is durationally significant,” he wrote. “It has already persisted for a full year and shows no sign of abating.”

Laster rejected Akorn's argument that even though its earnings were in the tank, it would bring valuable synergy to Fresenius, and that “as long as Fresenius can make a profit from the acquisition, [a material adverse effect] cannot have occurred.”

Nope.

“The [material adverse effect] definition does not include any language about the profitability of the deal to the buyer; it focuses solely on the value of the seller,” Laster wrote.

Cravath lawyers also blamed Akorn's dismal performance on “industry headwinds” that have affected the generic pharmaceutical industry since 2013. But Laster found that the problems were company-specific, and that Akorn was doing much worse than others in the industry.

And then there were the regulatory problems. Those too would “reasonably be expected to result in a material adverse effect. There is overwhelming evidence of widespread regulatory violations and pervasive compliance problems at Akorn,” the judge found.

He continued, “Akorn has gone from representing itself as an FDA-compliant company with accurate and reliable submissions from compliant testing practices to a company in persistent, serious violation of FDA requirements with a disastrous culture of noncompliance.”

Akorn, whose stock plunged more than 50 percent after the decision, said, “We are disappointed by the ruling by the Delaware Chancery Court determining not to force Fresenius to close and we continue to believe Fresenius' attempt to terminate the transaction is in breach of our binding merger agreement. We intend to appeal, in an effort to vigorously enforce our rights and continue to protect the interests of our company and our shareholders.”

What I'm Reading

After $250M Stock Sale, Litigation Funding Giant Plans to Raise More Capital

The new money, which Burford CEO Christopher Bogart said signals how strong demand is for the company's financing options, will be used to hire lawyers and business development team members in new markets, such as Australia, Germany and U.S. cities where Burford does not yet have a physical presence.

Tyco and 3M Ask for MDL Treatment in Dozens of Firefighting Foam Lawsuits

Stephen Raber, a partner at Williams & Connolly in Washington, D.C., filed the motion on behalf of Tyco and Chemguard, both part of Johnson Controls.

Would Kavanaugh Take the Supreme Court 'Express Train' to the Right?

If there are four votes to take up a major abortion case or a major gun case in the next few terms, we could see it happen in relatively short order.

Ex-Novak Druce Associate Sues Polsinelli in Standoff Over Fees

A former associate claims he is owed nearly $128,000 in fees generated by a client he introduced.

NY State Agency Says It's Looking Into Civil Tax-Fraud Claims Against Trump in Wake of Report

The scheme allegedly allowed the money to be given to Donald Trump and his siblings without having to pay any gift tax, which would have reduced the amount significantly.

Infowars Publisher Sues Paypal Claiming 'Viewpoint-Based Censorship': Read the Complaint

The publisher of the controversial Infowars website sued PayPal Inc. on Monday claiming that the payment site “discriminated against Plaintiff based on its political viewpoints and politically conservative affiliation.”

In case you missed it…

Daily Dicta: Lucky Ducks: Greenberg Traurig and Mintz & Gold Beat SEC in Insider Trading Case

SEC investigators couldn't crack the case—assuming there was a case, and not just investors blessed with super-fortuitous timing.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Litigators of the (Past) Week: Defending Against a $290M Claim and Scoring a $116M Win in Drug Patent Fight

Litigators of the Week: A Trade Secret Win at the ITC for Viking Over Promising Potential Liver Drug

Litigation Leaders: Mark Jones of Nelson Mullins on Helping Clients Assemble ‘Dream Teams’

Litigators of the Week: An Early Knockout Win in the Decongestant MDL

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250