These Two Men Have Been Jailed for Civil Contempt in North Carolina for Nearly Eight Years

Locked in a property rights battle with developers and a standoff with the legal system, Licrutis Reels and Melvin Davis refuse to obey a court to walk away from their family land. But a recent ruling from the state's highest court could open the door for their release.

November 26, 2018 at 05:51 PM

10 minute read

The original version of this story was published on Daily Report

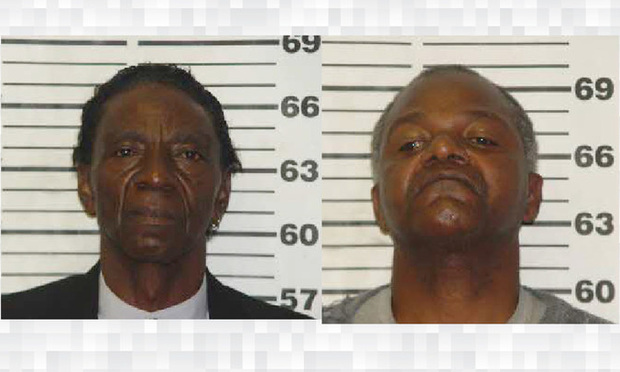

Melvin Davis (left) and Licurtis Reels

Melvin Davis (left) and Licurtis Reels

Some land is intertwined with a family's history and identity. Memories mingle among the trees. The marks of long-dead relatives speak through the soil.

“It was like paradise for me,” says Kim Duhon, remembering the childhood summers she spent on ancestral property in the Merrimon community on North Carolina's coast near the small town of Beaufort. “For me, it was everything.”

Duhon's father was in the U.S. Coast Guard, and she grew up in several port cities, including Boston and New Orleans. Summer was an exit from the confines of the big city and ushered in long days enjoying the North Carolina waterfront land that was part of Duhon's family for more than a century. For her, the land represented freedom. She could run and swim in the warm tidal creek that flowed along the edge of the property. She could be a kid.

But those halcyon days of Duhon's youth are gone, and the land that brought her joy as a child has become the epicenter of an unbelievable property rights battle tinged with racial tension.

The fight involves Duhon's entire family, but her uncles Melvin Davis and Licurtis Reels have sacrificed the most. After living on the property, they have spent nearly eight years in jail for civil contempt because they will not back down in a standoff with the legal system and a developer, Dean Brown, over ownership of the land.

The state's trial and appellate courts have repeatedly held that Brown and his company, Adams Creek Associates, are the owners. Adams Creek filed a trespassing action to get Davis and Reels off the land, but the two men have refused to acknowledge the court rulings or obey an order that requires them to demolish their homes on the land. They also have refused a court order to declare in writing that they'll never return.

Their denials spurred local Superior Court Judge Jack Jenkins to order that the pair be imprisoned for civil contempt on March 17, 2011. Jenkins found that Davis and Reels were in contempt of a 2004 summary judgment order, which held that Brown owned the land and required Davis and Reels to leave.

They have been locked in a county jail ever since.

No one else has ever been held this long for civil contempt in North Carolina—or just about anywhere else in the country for that matter.

H. Beatty Chadwick of Pennsylvania still holds the record. He spent 14 years in jail for civil contempt, because the court believed he was hiding millions of dollars in an overseas account to prevent his wife from getting her hands on the money during their divorce.

But Chadwick's case isn't comparable to the Davis and Reels saga. He argued that the money was gone, lost in poor investments, and he simply couldn't comply with the court's order. By contrast, Reels and Davis have testified they simply wouldn't comply with the court's order, even if they could, because they believe the land is theirs.

'This is not about the money.'

The dispute is rooted in a judge's ruling in 1971 that the 13 acres in question belonged to Davis and Reels' mother after her husband died without a will. The judge also found that the husband's 11 children shared ownership of the land. But then the husband's brother, Shedrick Reels, came to town and built a house on the property.

Shedrick Reels staked his claim on the land with an adverse possession and “Torrens action” in 1978. To secure a Torrens title, Shedrick Reels filed a petition with the court that described the property and, as required, identified anyone else who might also assert ownership. They had a year to come forward with their claim. When that didn't happen, Shedrick Reels cemented his right to the land with an ironclad Torrens title. He later sold the land to the developers who would sell the property to Brown.

Duhon says her now-jailed uncles and others who had title to the land didn't speak up during the contestable phase of the Torrens process because they “had no clue” what was going on, until it was too late.

“That's what makes this so heart-wrenching for the family,” she says.

She and her relatives are concerned that Brown, who is white, will turn the land into a high-end development and raise surrounding property taxes in what is a predominantly black and impoverished area. Davis, Duhon and Reels are black. And so is just about everyone who lives around the land, Duhon says. She estimated that there are about 50 residents.

“This is not about money. It's about principle and our heritage,” she says.

'My clients have no malice.'

It's a morbid possibility but one that looms over the story: The main players in the case might not survive the dispute. In fact, one has already died. Originally, Brown and a business partner in Adams Creek Associates intended to develop the land. But that partner passed away during the protracted dispute with Davis and Reels, and his interest in the property was transferred to Brown's wife. Both Browns are now in their 80s.

The Browns' attorney, Lamar Armstrong Jr. of Smithfield, says his clients' have shelled out more on legal costs than they paid for property, which sits undeveloped. They have offered to sell the land to Davis and Reels, but without success.

“My clients have no malice toward them,” Armstrong adds. “They're tired. They've spent a lot of money. But they would take far less [for the land] than what it would be worth if it were to be developed.”

It's unlikely that Davis and Reels would buy the land from the Browns. There's the principle. And also the issue of money. The two have asserted that they can't cover the cost of demolishing the structures on the land. Before they were jailed, Reels worked as a brick mason, and Davis had a shrimping company and a small demolition business, though his equipment is no longer operational, Duhon says.

She says her uncles weren't wealthy before all this started and, of course, they haven't been making money in jail. So it stands to reason that they can't afford the land, in the unlikely event that they wanted to buy it from the Browns.

Supreme Court ruling tees up new question.

Davis is 71 years old. Reels is a decade younger, but he's severely diabetic. When Duhon visits them in jail, she says they talk about “how unjust this situation is” and, of course, the land.

“This property situation is what they eat and breathe,” she adds.

Their Raleigh-based attorney, James Hairston, declined a request to interview Davis and Reels in jail while their case is pending. He says their ”health has been deteriorating every year since they've been there [in jail], but hopefully that will change soon.”

Hairston, the latest in a string of lawyers who have provided pro bono representation to Davis and Reels over the years, is sounding slightly more optimistic about the case these days. He and his clients are buoyed by a per curiam decision that the state Supreme Court issued on Sept. 21. They believe that it could provide a key to freedom.

The high court kicked the case back to the trial level to determine whether Davis and Reels can comply with the part of the order to raze their homes. That question should be easy to answer. But the court also included a curious line in the decision: “In the trial court, defendants also are without prejudice to advance claims not briefed or previously raised but discussed at oral arguments before this Court.”

That line allows Davis and Reels to argue, for the first time at the trial level, that it would be unconstitutional for the court to force them to say or write something. If this new argument succeeds, it would presumably erase the part of the order requiring them to attest that they don't own the land.

“The written attestation piece is a throwaway if they don't have the ability to comply” with the court's order to tear down the structures on the land, Hairston says.

Armstrong—the Browns' lawyer—has a different take. He says this isn't a free speech issue. It's about action.

“This is conduct being regulated,” he says. “I don't care what they think or believe. They can believe the courts are wrong. But they've gotta say 'we don't own it' and 'we're not going on it.' That's conduct.”

'At one point, we had a vision.'

A trial judge could hear the case before the end of the year. Whatever the ruling, the matter is bound to return to the state Supreme Court, where something might finally give in this war of attrition.

In earlier decisions, “there's been a strong desire to embrace the rule of law. But that's starting to erode because of the passage of time,” Armstrong says.

“It's become politically incorrect now,” he adds. “Seven-and-a-half years bothers everybody. I get that. It's easy and seductive to go from that to giving up a position that otherwise the judicial system would cling to tightly. Somebody being stubborn cannot outweigh the rule of law.”

But if the court backs down and releases Davis and Reels, what happens then? Will they quietly walk away and restart their lives in a new place? Or will they return to their family land and be arrested for trespassing? What's their future?

Asked how she thinks the story will end, Duhon hesitates a moment.

“At this point, I don't even know,” she says. “At one point, we had a vision. But we've gone through this so long that I don't even see what our vision is anymore.”

But then she adds, “I just know that we won't give up.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

An ‘Indiana Jones Moment’: Mayer Brown’s John Nadolenco and Kelly Kramer on the 10-Year Legal Saga of the Bahia Emerald

Travis Lenkner Returns to Burford Capital With an Eye on Future Growth Opportunities

Legal Speak's 'Sidebar With Saul' Part V: Strange Days of Trump Trial Culminate in Historic Verdict

1 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Recent Controversial Decision and Insurance Law May Mitigate Exposure for Companies Subject to False Claims Act Lawsuits

- 2Visa Revocation and Removal: Can the New Administration Remove Foreign Nationals for Past Advocacy?

- 3Your Communications Are Not Secure! What Legal Professionals Need to Know

- 4Legal Leaders Need To Create A High-Trust Culture

- 5There's a New Chief Judge in Town: Meet the Top Miami Jurist

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250