Nixon Peabody and Boies Schiller Prep for Courtroom Clash Over Nazi-Looted Pissarro Masterpiece

It will be up to U.S. District Judge John Walter in Los Angeles to decide whether a Swiss Baron and Spanish Foundation held good title to the painting and whether the Foundation knowingly received stolen property.

November 30, 2018 at 12:33 PM

5 minute read

The original version of this story was published on The Recorder

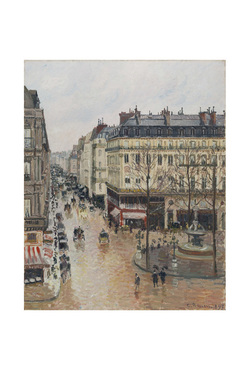

Camille Pissarro''s painting Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon, Effect of Rain, 1897, hung in the parlor of the Cassirer family home in Germany before the Nazis seized it in 1939. (Courtesy photo)

Camille Pissarro''s painting Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon, Effect of Rain, 1897, hung in the parlor of the Cassirer family home in Germany before the Nazis seized it in 1939. (Courtesy photo)

In a trial more than a decade in the making, lawyers at Boies Schiller Flexner and Nixon Peabody are set to square off starting Dec. 4 in a Los Angeles federal courtroom for three days to decide the fate of a Nazi-looted painting by French impressionist Camille Pissarro.

A Boies Schiller team led by David Boies himself and Miami-based partner Stephen Zack will make the case that the descendants of Lilly Cassirer Neubauer are the rightful owners of Pissarro's “Rue Saint-Honoré, après-midi, effet de pluie.” Neubauer, the great-grandmother of the Cassirer plaintiffs, lost the painting in 1939 after a Nazi-appointed art dealer seized it to conduct an appraisal and valued it at the modern equivalent of $360. The masterpiece since has been appraised at more than $30 million.

Camille Pissarro's painting Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain, 1897. (1976.74), at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid.

Camille Pissarro's painting Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain, 1897. (1976.74), at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid.“The principle involved here—that no person should never be able to hold good title for a property that has been looted—is a critical principle in today's world,” said Boies Schiller's Zack in a phone interview.

On the defense side, a Nixon Peabody team that includes art law expert Thaddeus Stauber is set to represent Madrid-based Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation, which is tasked with managing a collection of art acquired by the Spanish state, including the Pissarro at issue. The Foundation's legal team has argued that under Spanish law it is presumed to have acquired the painting in good faith.

Likewise, the defense also argues Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, the Swiss magnate who previously owned the painting, has that same good faith presumption under Swiss law. The plaintiffs, the Nixon Peabody lawyers claim, don't have evidence showing that either the Foundation or the Baron acquired the painting with knowledge of its Nazi-looted past.

A Nixon Peabody spokeswoman said this past week that no member of the defense team was available for comment. But the defense wrote in their trial brief that the “red flags” that the plaintiffs claim should have alerted the Baron and the Foundation to the paintings' troubling past were merely “hindsight-driven speculation and inferences.”

“Because Plaintiffs' 'evidence' does not suggest, much less prove, that the Foundation had actual knowledge of the Painting's wartime looting until Mr. Cassirer's 2001 petition, the Foundation cannot, under any legal theory, be deemed an encubridor,” wrote the Nixon Peabody lawyers, referring to the Spanish legal term for for accessory to a crime.

Mary-Christine “M.C.” Sungaila of Haynes and Boone, who wrote an amicus brief for Bet Tzedek Legal Services backing the Cassirers in the case when the case was on its most recent—and third trip—to the Ninth Circuit on appeal, said it's “a rarity in the realm of Holocaust art restitution”: A case that is actually going to trial, rather than being decided on sovereign immunity grounds or under some statute of limitations.

Now it will be up to U.S. District Judge John Walter in Los Angeles to decide whether the Baron and the Foundation held good title to the painting and whether the Foundation knowingly received stolen property.

A Question of Provenance?

Some of the key evidence in the case lies in a location where folks outside of the art world probably wouldn't think to look: The back of the painting. The Nixon Peabody lawyers note that the Pissarro lacks the markings from Nazi agencies and suspicious customs stamps that are often “red flags” for looted art. The Boies Schiller lawyers, on the other hand, point out in their trial brief that the back of the painting had evidence of numerous removed labels.

“There is no legitimate reason to tear off these labels as they serve the dual purpose of fortifying an artwork's authenticity and increasing its value,” the Boies Schiller lawyers wrote. “The removal of such labels is like filing the serial number off a stolen gun or the VIN number on a motor vehicle—clear causes for concern.”

On top of the missing labels, the Boies lawyers point to one partial label that remains: a torn gallery label that says “Berlin” they claim irrefutably ties the painting to the Cassirer Gallery.

“There was no effort to really look at the provenance here” by the Baron or TBC, said Boies Schiller's Zack in a phone interview.

The Foundation's lawyers, however, say that the label is not sufficient evidence to overcome its presumption of good faith.

“From the label, four words are legible: 'Kunst' ('art' in German), 'und' ('and' in German), 'Berl n,' and 'Pissarro,'” the Nixon Peabody lawyers write. “From this, Plaintiffs extrapolate that the Foundation should have known the artwork was once in Bruno and Paul Cassirer's art gallery in Berlin.”

The defense lawyers argue that even if that connection were made, there's no reason to connect that gallery, which they say closed in 1901, with Nazi looting or Lilly Cassirer Neubauer.

But the Boies lawyers say that what's at issue isn't whether defendants knew that painting was taken from Lilly Cassirer Neubauer.

“The issue is whether the Baron and TBC knew the Painting had been stolen, full stop,” they wrote.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

An ‘Indiana Jones Moment’: Mayer Brown’s John Nadolenco and Kelly Kramer on the 10-Year Legal Saga of the Bahia Emerald

Travis Lenkner Returns to Burford Capital With an Eye on Future Growth Opportunities

Legal Speak's 'Sidebar With Saul' Part V: Strange Days of Trump Trial Culminate in Historic Verdict

1 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Many LA County Law Firms Remain Open, Mobilize to Support Affected Employees Amid Historic Firestorm

- 2Stevens & Lee Names New Delaware Shareholder

- 3U.S. Supreme Court Denies Trump Effort to Halt Sentencing

- 4From CLO to President: Kevin Boon Takes the Helm at Mysten Labs

- 5How Law Schools Fared on California's July 2024 Bar Exam

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250