Litigators of the Week: Wilmer Team Makes the Grade for Harvard and Diversity

'As one of the few cases of this type to go through a full (and very public) trial, we hope this case will be an example of how important it is for courts considering challenges like this to really hear the evidence and understand the process,'

October 04, 2019 at 12:16 AM

11 minute read

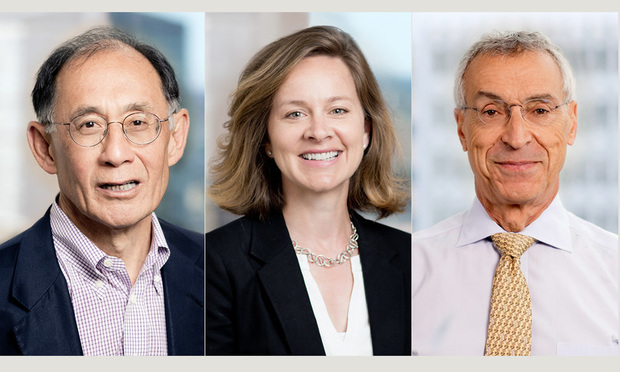

L-R William Lee, Felicia Ellsworth and Seth Waxman, Wilmer Hale.

L-R William Lee, Felicia Ellsworth and Seth Waxman, Wilmer Hale.

Our Litigators of the Week are Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr's Seth Waxman, William Lee and Felicia Ellsworth for their front-page win defending Harvard University's race-conscious admissions system.

The Ivy League school was sued by Students for Fair Admissions Inc. and its chief Edward Blum. Represented by Consovoy McCarthy and Bartlit Beck, they alleged Harvard violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by limiting the number of Asian American applicants accepted.

In a powerful opinion, U.S. District Judge Allison D. Burroughs of the District of Massachusetts on Sept. 30 sided with Harvard, writing that "race-conscious admissions programs that survive strict scrutiny will have an important place in society and help ensure that colleges and universities can offer a diverse atmosphere that fosters learning, improves scholarship, and encourages mutual respect and understanding."

The Wilmer team discussed the case with Lit Daily.

How did you come to represent Harvard in this case?

From the outset, most people assumed that this case was headed to the Supreme Court. Harvard retained Seth with that in mind, both because Harvard recognized that an appellate and Supreme Court strategy would be needed from the start, and because of WilmerHale's long history of representing universities whose pursuit of diversity has been challenged—in particular, our former partners John Pickering and John Payton, who successfully defended the University of Michigan's policy in Grutter v. Bollinger.

Seth assembled a team of experienced trial and appellate lawyers to handle the case, and as it became clear that a full trial would be needed, Bill joined the team.

We couldn't pick the whole team for Litigator of the Week. But tell us about the other members and their contributions at trial—and why it was important that Harvard be represented by a diverse group of lawyers.

In many ways, our team was diversity in bold relief. The team was a wonderful collection of senior and junior lawyers which itself was diverse on many dimensions—ethnically, racially, by gender, by geography, and by practice area.

At trial, in addition to Bill, Seth, and Felicia, Harvard's case was presented by Danielle Conley from WilmerHale and Ara Gershengorn from Harvard's Office of General Counsel. So, of the five of us, there were three women, one Asian American lawyer and one African American lawyer trying the case. And, the more junior members of the team were equally diverse on all dimensions.

There were a large number of witnesses who testified at trial in this case, nearly all of whom were Harvard employees or former employees, so the members of the case team who did not have a stand-up role at trial had an equally (arguably more) important role working with the many witnesses to prepare for their trial testimony.

Bill and Seth, you both got your undergraduate degrees from Harvard, Bill in 1972 and Seth in 1973. What was on-campus diversity like then? How did your personal experiences as Harvard students affect your feelings about litigating the case?

When we went to Harvard, the school was in the midst of a transition, pioneered by President Conant, to open the college to different groups of students from different economic and ethnic backgrounds. As a first generation Chinese-American, and a Jewish public-school kid from a working class family, we were both beneficiaries of those efforts.

But the college was still very different then. There were 1200 men and 400 women. Private school graduates predominated. And while affirmative action in admissions had begun in earnest, there was relatively little economic diversity and few first-generation students. And, Bill knew all of the Asian Americans in his class, as there were so few. This has all changed.

That said, even then the diversity in the undergraduate class was perhaps the most important element in our educational experience. We were told, and rightly so, that we would learn as much or more from our classmates as from our professors. Living and interacting with students from a wide range of backgrounds and consequent worldviews enriched and changed our lives.

The plaintiffs alleged Harvard intentionally discriminates against Asian American applicants. As an Asian American, did that give you pause Bill?

I am immensely proud to be a Chinese American. My parents immigrated to the United States at a time when Chinese immigrants were barred by statute from citizenship. I sat with my mother while our neighbors voted on the restrictive covenants and decided whether they wanted our family as neighbors.

We experienced racism and discrimination on many occasions, including as recently as 2016 as The American Lawyer reported. I abhor discrimination on any basis and would never countenance it. If I thought Harvard was discriminating against Asian Americans or anyone else, I would say so. But, as the court found, and as I know, Harvard has not and does not.

From the beginning, this case attracted tremendous interest. How did you deal with the spotlight? Did you calibrate your litigation strategy knowing a wide audience was following the litigation?

We certainly were aware that the case would attract a great deal of interest, but we approached the case as lawyers. The court, not the press, was our audience, and we kept that front of mind. That meant digging into the facts and the law like we would in any other case, and crafting a litigation and trial strategy that would allow the court to really understand what Harvard does, why Harvard does it, and what Harvard doesn't do.

As we've seen in the college admissions scandal, the process has become so fraught for students and parents. This case meant digging deep into the Harvard admissions process. What did you find?

We found a thorough process staffed by dedicated admissions officers with many checks and balances. The opinion describes this process in detail, and the many admissions officers who testified at trial explained the care and thought with which they approach their responsibility, in testimony that was, as the judge said "consistent, unambiguous, and convincing."

In the end, every applicant receives full and fair consideration, and every admitted student is discussed and receives a positive vote by the group of over 40 admissions officers in an open meeting.

What did you make of DOJ's statement of interest in the lawsuit?

Two years after this suit was filed, the Department of Justice opened an investigation of Harvard covering the same matters. As that investigation remains open, we're unable to comment.

There's a long line of cases dealing with affirmative action and college admissions. Where does this one fit in?

Harvard's admissions process was recognized decades ago as a model for the permissible use of race in college admissions; indeed, it was held as the paradigm in Justice Powell's controlling opinion in Bakke. This case was never really about whether Harvard's admissions process passes muster—as Judge Burroughs found, it does; instead, it was brought to challenge the long line of cases, beginning with Bakke, upholding the use of race as one factor among many to achieve a university's compelling interest in diversity.

That said, as one of the few cases of this type to go through a full (and very public) trial, we hope this case will be an example of how important it is for courts considering challenges like this to really hear the evidence and understand the process, as we think Judge Burroughs' opinion makes clear she did.

Take us inside the courtroom when the case went to trial last October—what were some of the high (or low) points?

One of the high points in the trial was the testimony from current and former Harvard students, who were allowed to participate in the trial as amici. The judge set aside a full day to hear this deeply personal, and powerful, testimony, and the student voices laid bare how deeply important diversity is to Harvard students, while also showing, as the judge recognized, that there is still work to be done.

Another important moment in the case was the testimony of Dr. Ruth Simmons, who provided powerful testimony about the importance of diversity to institutions of higher education and society. Her testimony was some of the most moving in the case, and the entire courtroom was rapt as she spoke—you could hear a pin drop. The judge called her testimony "perhaps the most cogent and compelling testimony presented at this trial," and quoted it at length in her opinion—it was an incredibly powerful and important moment in the trial.

As in any long trial, there were moments of levity as well. For example, when Bill was examining the Dean of Admissions, William Fitzsimmons, he asked Dean Fitzsimmons if he took allegations of discrimination "seriously." Unfortunately, Bill's iPad was on the lectern, and instead of Dean Fitzsimmons responding to that important question, Siri asked Bill: "How can I help you?"

The trial was unusual in that the plaintiff called no fact witnesses of its own. Instead, it presented its case by hostile direct examination of Harvard's witnesses (who we then examined on "cross" examination). The plaintiff's manifest strategy was to discomfit our witnesses by subjecting them to cross-examination before they could present their direct evidence. Their powerful, consistent testimony was a testament to the strength of Harvard's commitment to inclusion and nondiscrimination and to the integrity of an admissions process that evaluates, and values, every applicant as a unique individual.

The plaintiffs didn't present any Asian American witnesses who could testify to having been wrongly denied admission. Was that a key weakness?

It was a glaring deficiency and the judge identified it as such. Midway through the trial the court asked plaintiff's counsel again whether they intended to call any witnesses, or introduce any admissions files, evidencing a specific example of race discrimination, and said that they could do so even though the date for identifying any such witnesses or documents had long since passed.

All of the other Supreme Court cases relating to the use of race in university admissions—Bakke, Grutter, Gratz, Fisher—have a name associated with them because there was a person who claimed to be the victim of discrimination. After years of discovery, SFFA presented no witness, no file, and no applicant that it could argue had been discriminated against. In our view, that was not a coincidence. And the judge agreed.

What to you are some of the most important (or gratifying) parts of the opinion by Judge Burroughs?

The opinion is thorough, thoughtful, detailed and nuanced. The court's detailed findings of fact will provide reviewing courts the essential background for the legal issues the plaintiff intends to present for appellate review. The court's recognition of the importance of diversity at this point in our history, the critical role educational institutions play in fostering a more diverse society and the manner in which Harvard is constitutionally striving to achieve those goals were all gratifying.

The plaintiffs have already said they plan to appeal. Have you been litigating all along with the expectation of appellate review? Would you be surprised if this case winds up before the U.S. Supreme Court?

We did expect that this case would be appealed, whatever the outcome in front of Judge Burroughs, and, like plaintiff's counsel, we certainly kept the broader appellate audience in mind in litigating the case. As to steps beyond the direct appeal to the First Circuit, it's impossible to predict. We think Judge Burroughs' decision was thoughtful and careful, and hope any other court that may have occasion to review her ruling will agree.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Litigators of the Week: Shortly After Name Partner Kathleen Sullivan’s Retirement, Quinn Emanuel Scores Appellate Win for Vimeo

Shareholder Democracy? The Chatter Elon Musk’s Tesla Pay Case Is Spurring Between Lawyers and Clients

6 minute read

In-House Lawyers Are Focused on Employment and Cybersecurity Disputes, But Looking Out for Conflict Over AI

Trending Stories

- 1Bribery Case Against Former Lt. Gov. Brian Benjamin Is Dropped

- 2‘Extremely Disturbing’: AI Firms Face Class Action by ‘Taskers’ Exposed to Traumatic Content

- 3State Appeals Court Revives BraunHagey Lawsuit Alleging $4.2M Unlawful Wire to China

- 4Invoking Trump, AG Bonta Reminds Lawyers of Duties to Noncitizens in Plea Dealing

- 522-Count Indictment Is Just the Start of SCOTUSBlog Atty's Legal Problems, Experts Say

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250