SCOTUS to Hear Major Challenge to Independence of Obama-Era Consumer Bureau

A team from Paul Weiss, led by appellate veteran Kannon Shanmugam, convinced the justices to hear a constitutional challenge to the single-director power scheme at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

October 18, 2019 at 03:38 PM

5 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

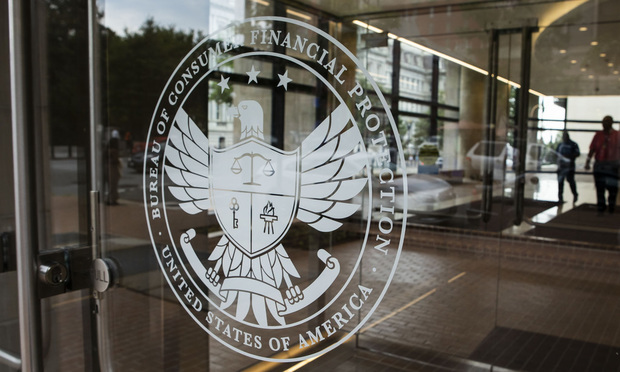

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau headquarters in Washington, D.C. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau headquarters in Washington, D.C. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

The U.S. Supreme Court, jumping into a second separation-of-powers case this term, agreed Friday to decide the constitutionality of the single-director structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, an agency long criticized by the business community and Republican leaders on Capitol Hill.

The challenge to the independent federal agency created by Congress in the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform law was brought by California-based Seila Law, which provides legal services to consumers, including assistance with the resolution of consumer debt. Seila Law is represented by Kannon Shanmugam, a partner at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison.

The CFPB issued a civil investigative demand seeking information and documents from the law firm in an investigation into whether it violated certain federal laws. Seila objected to the demand, claiming that the agency was unconstitutionally structured. The CFPB petitioned a federal district court for enforcement, which was granted. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court's ruling that the agency's structure did not violate the separation of powers.

In his petition, Shanmugam argued that the CFPB director alone decides what rules to issue, how to enforce the law and what penalties to impose on those who violate the law.

That combination of power concentrated in a single person who can only be removed by the president for cause "raises grave constitutional concerns," Shanmugam wrote. He also told the justices that a decision upholding the CFPB structure "could provide a blueprint for Congress to reshape the executive branch in dramatic fashion."

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who formerly sat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, has lambasted the single-director power scheme at the consumer bureau. In an unrelated court challenge, he called the director one of the most "powerful" leaders in all of Washington. "Indeed, other than the president, the director of the CFPB is the single most powerful official in the entire United States government, at least when measured in terms of unilateral power," Kavanaugh wrote in one case.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

Justice Brett Kavanaugh. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALMThe U.S. Justice Department defended the consumer agency's constitutionality for years. But under the Trump administration, the government abandoned that position and argued that the agency's structure was unconstitutional. The consumer bureau itself recently switched sides, backing Seila Law's challenge.

The court added a second question for argument: If the justices strike down the CFPB's single-director structure as unlawful, can it be severed from the whole of the Dodd-Frank Act? The Justice Department has argued that the remedy in the case "is to sever the provision limiting the president's authority to remove the bureau's director." The Justice Department has urged the court to leave the remainder of the Dodd-Frank law intact.

"Absent the for-cause removal provision, the Dodd-Frank Act and its bureau-related provisions will remain 'fully operative,'" the Justice Department said in its filing at the high court.

Lawyers for the U.S. House of Representatives, lining up against the Trump administration's Justice Department, have urged the high court to uphold the Ninth Circuit ruling. The Supreme Court is expected to appoint a friend-of-the-court to argue in defense of the Ninth Circuit's decision.

Two other petitions attacking single-director agency structures were filed in recent weeks: Collins v. Mnuchin and All-American Check Cashing v. CFPB. An appellate team at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, including former U.S. Solicitor General Theodore Olson and Helgi Walker, a leader of the firm's regulatory group, argued earlier that the court should have granted its challenge to the CFPB.

The other case this term raising separation-of-power concerns involves the appointment of members to the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico v. Aurelius Investment. The board and the Trump administration argued that the First Circuit erred in deciding that the appointment of the board's members violated the Constitution's appointments clause. That case was argued Oct. 15.

Read more:

Paul Weiss Pokes Gibson Dunn in New SCOTUS Brief in Consumer Bureau Case

Appellate Veterans Jockey at SCOTUS to Contest Consumer Bureau

CFPB, Changing Stance, Backs Law Firm Fighting Agency's Independent Design

D.C. Circuit's Brett Kavanaugh Doubles Down on Criticism of CFPB

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Litigators of the Week: US Soccer and MLS Fend Off Claims They Conspired to Scuttle Rival League’s Prospect

‘Listen, Listen, Listen’: Some Practice Tips From Judges in the Oakland Federal Courthouse

Trending Stories

- 1Judge Grills DOJ on Trump’s Birthright Citizenship Executive Order

- 2Exceptional Growth Becoming the Rule? Demand and Rate Hikes Drove Strong Year for Big Law

- 3Dentons Taps D.C. Capital Markets Attorney for New US Managing Partner

- 4Auto Dealers Ask Court to Pump the Brakes on Scout Motors’ Florida Sales

- 5German Court Orders X to Release Data Amid Election Interference Concerns

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250