Swirl of Ethics Questions Raised by Boies' Alliance With Epstein 'Hacker'

A reported effort by lawyers David Boies and Stan Pottinger to obtain years' worth of Jeffrey Epstein's sex tapes has some legal ethics experts wondering: Did the lawyers cross a line, or might they have eventually?

December 02, 2019 at 06:26 PM

7 minute read

The original version of this story was published on New York Law Journal

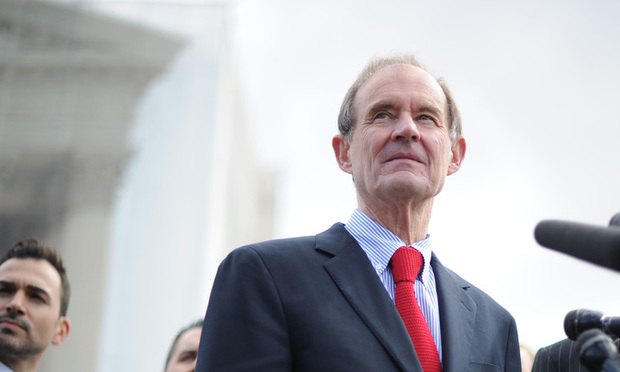

David Boies outside the U.S. Supreme Court, March 23, 2013. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM

David Boies outside the U.S. Supreme Court, March 23, 2013. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM

A recent New York Times story on efforts by lawyers David Boies and Stan Pottinger to obtain surveillance footage from Jeffrey Epstein's mansion has it all: A pseudonymous whistleblower. Grainy surveillance footage. Self-destructing files. And a potential holy grail of evidence for alleged victims of Epstein's sex-trafficking ring.

And it has something more: a host of potential legal ethics problems, according to professors and practicing attorneys in the field who spoke to the New York Law Journal.

The Times report detailed, in 5,000 words, how a mysterious self-styled hacker calling himself Patrick Kessler convinced Boies, the famed litigator and Boies Schiller Flexner chairman, and Pottinger, a friend of his whose firm Edwards Pottinger works on sex-abuse cases, that he had access to years' worth of emails, financial records and surveillance tapes from Epstein's Manhattan mansion that depicted billionaires, politicians and CEOs in sexually compromising situations, even committing rape.

The plan ultimately went nowhere. Kessler produced grainy stills that he claimed depicted Alan Dershowitz and the Israeli politician Ehud Barak in sexual scenarios. (They denied ever having engaged in sexual activities at Epstein's home.) He bailed on a plan to give copies of his servers to the Times, however, and the newspaper said it had no evidence that any of the evidence described even existed.

But the Times' story was full of details of behind-the-scenes negotiations among Kessler, Boies and Pottinger about how to do justice to the women depicted in the videos—and how to make money for themselves in the process.

Most of the communications described in the story were between Kessler and Pottinger, who is quoted describing two ways to monetize the supposed evidence. One was to find the women depicted in the videos and to ink settlements with the powerful men who raped them, splitting the proceeds among the victims, the lawyers, Kessler and an anti-abuse charity they would create. Another was to approach the men from the videos and agree to represent them and keep the videos from becoming public, in exchange for a payment to the charity.

Taking the Times report at face value, both hypothetical proposals have problems, two experts said. To begin with, there could be issues with how Kessler obtained the cache of evidence. If he stole it from the Epstein estate, it would be unethical to use it. If, however, he had legitimate access to the cache and merely breached a duty to keep it confidential, that breach wouldn't have been a concern of Boies and Pottinger, said Stephen Gillers, a legal ethics professor at New York University.

"Receiving stolen property is a crime," Gillers said in an interview. But "the fact that the source of the information is violating a duty to somebody else … does not prevent the lawyer from receiving or using the information."

The first proposal—to find the women in the supposed videos and persuade them to hire Boies and Pottinger—could be challenging because of a lack of identifying details. It also would have been unethical to split fees with Kessler in such a scenario, because witnesses can only be paid for their time and expenses, said Ellen Yaroshefsky, an associate dean and professor of legal ethics at Hofstra Law.

The second proposal, which would have entailed approaching the men in the videos and having them hire Boies and Pottinger, was more ethically fraught, according to attorneys interviewed for this story. Boies currently represents several victims of Epstein's alleged sex-trafficking ring, and representing an alleged predator could pose a conflict with that work, said Chris McDonough, a legal ethics lawyer who is special counsel at the firm Foley Griffin.

"One should be careful about one's duty of loyalty to former clients," said Rebecca Roiphe, a professor at New York Law School, who made a similar point.

The Times said that when it pressed Pottinger about his exchanges with Kessler, he said he had been deceiving Kessler in an effort to get the servers. He said he never intended to represent Kessler or to pursue the strategies he described to him in messages seen by the Times, saying, "I didn't owe Patrick honesty about this," the paper reported.

But that raises another set of questions, said David A. Lewis, a legal ethics attorney who has his own firm in Manhattan. Several New York Rules of Professional Conduct prohibit dishonesty to adversaries and non-clients. There are some cases where lawyers or their investigators can lie—for instance, to expose housing discrimination—but courts are "reluctant" to permit such conduct outside of a few "narrow" exceptions, he said.

Pottinger didn't respond to a request for comment left at his law offices.

Alan Dershowitz, a longtime adversary of Boies who was reportedly said by Kessler to have been taped in a compromising sexual scenario, said he and his lawyers are considering "all of our legal options" in response to the what the Times reported about Boies and Pottinger. He said the story revealed an apparent "pattern of extortion" that mirrors how he claims Boies approached Les Wexner, the billionaire businessman who has been reported to be close with Epstein.

The Times reported that Boies seemed angry to see some of Pottinger's communications with Kessler, but said he was reluctant to cast blame on his friend.

In a statement for this story, a Boies Schiller representative defended the firm's work and disputed parts of the Times' reporting. A quote in which Boies said Kessler could have been paid "generously" for his information was "not an accurate quote," the spokesman said. While the firm declined to say whether it told its victim-clients about the supposed video evidence or its plans for the videos, it did say that "neither Mr. Boies nor anyone else from BSF ever discussed the possibility of representing alleged abusers."

The spokesman said Boies had alerted the FBI and federal prosecutors about their contacts with Kessler and would have consulted them and BSF's ethics counsel before undertaking any further steps to obtain the evidence Kessler claimed to have. Asked whether Kessler had a right to share the supposed evidence cache and whether Boies could have used it, the firm said yes.

"We did not and do not believe that Epstein's estate had any right to prevent his former IT consultant from revealing to us physical evidence in his lawful possession of crimes committed against our clients," the firm's statement said.

It's not clear whether an attorney grievance committee would consider acting on the Times reporting. Yaroshefsky, the Hofstra professor, said she thought it was unlikely, because Boies "is smart, and he knows what he's doing."

Roiphe, of New York Law School, said between Boies's work for Harvey Weinstein and the fraud-wracked blood-testing startup Theranos, the biggest threat he faces might be to his reputation as an aggressive litigator who is also seen as "brilliant and respectable."

"I do think it's starting to affect his credibility in certain circles," she said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

With DEI Rollbacks, Employment Lawyers See Potential For Targeting Corporate Commitment to Equality

7 minute read

MoFo Associate Sees a Familiar Face During Her First Appellate Argument: Justice Breyer

Amid the Tragedy of the L.A. Fires, a Lesson on the Value of Good Neighbors

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Day Pitney Announces Partner Elevations

- 2The New Rules of AI: Part 2—Designing and Implementing Governance Programs

- 3Plaintiffs Attorneys Awarded $113K on $1 Judgment in Noise Ordinance Dispute

- 4As Litigation Finance Industry Matures, Links With Insurance Tighten

- 5The Gold Standard: Remembering Judge Jeffrey Alker Meyer

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250