Daily Dicta: How NOT to Litigate During a Pandemic

"The filing calls to mind the sage words of Elihu Root: 'About half of the practice of a decent lawyer is telling would-be clients that they are damned fools and should stop.'"

March 23, 2020 at 10:57 PM

5 minute read

Look, I get it—everyone wants to be a zealous advocate, to protect your client, to push for the maximum remedies available.

Look, I get it—everyone wants to be a zealous advocate, to protect your client, to push for the maximum remedies available.

But at this moment in time, some perspective is in order. As in, if your case involves stopping the sale counterfeit unicorn products on the internet, sorry, that's not an emergency. You need to chill out.

That was the message from U.S. District Judge Steven Seeger, who was a partner at Kirkland & Ellis before he was confirmed to a seat in the Northern District of Illinois in September.

Last week, Seeger penned a withering decision denying a request for a temporary restraining order that was filed by Michael A. Hierl, a partner at Hughes Socol PIers Resnick & Dym in Chicago.

Hierl, who did not respond to a request for comment, represents Art Ask Agency, the exclusive licensee for the fantasy art of British artist Anne Stokes, who is popular among the Dungeons and Dragons crowd.

Hierl, who did not respond to a request for comment, represents Art Ask Agency, the exclusive licensee for the fantasy art of British artist Anne Stokes, who is popular among the Dungeons and Dragons crowd.

On March 18, he asked the court for an emergency TRO, ex parte asset freeze and expedited discovery involving a slew of third parties including Amazon, Visa, PayPal, Western Union, Facebook and Google.

"Without entry of the requested emergency relief, the sale of infringing products will continue unabated. Therefore, entry of an emergency ex parte order is necessary to protect plaintiff's rights, to prevent further harm to plaintiff and the consuming public, and to preserve the status quo," Hierl wrote.

Seeger was … not persuaded.

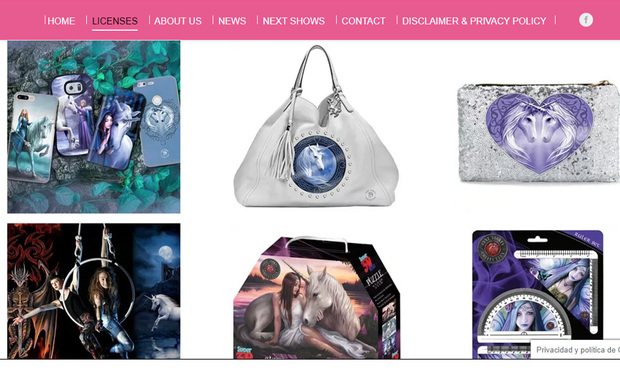

His order—just over two pages long—kicks off with a less-than-reverent description of the products at issue: "One example is a puzzle of an elf-like creature embracing the head of a unicorn on a beach. Another is a hand purse with a large purple heart, filled with the interlocking heads of two amorous-looking unicorns. There are phone cases featuring elves and unicorns, and a unicorn running beneath a castle lit by a full moon."

"Meanwhile," the judge continued in what was surely a deliberately jarring contrast, "the world is in the midst of a global pandemic. The president has declared a national emergency. The governor has issued a state-wide health emergency. As things stand, the government has forced all restaurants and bars in Chicago to shut their doors, and the schools are closed, too. The government has encouraged everyone to stay home, to keep infections to a minimum and help contain the fast-developing public health emergency."

Given these circumstances, Seeger scheduled the TRO hearing a few weeks out "to protect the health and safety of our community, including counsel and this court's staff. Waiting a few weeks seemed prudent."

Besides, he noted, "Plaintiff has not demonstrated that it will suffer an irreparable injury from waiting a few weeks. At worst, defendants might sell a few more counterfeit products in the meantime. But plaintiff makes no showing about the anticipated loss of sales. One wonders if the fake fantasy products are experiencing brisk sales at the moment."

(Pandemic must-haves: Toilet paper, hand sanitizer, N95 masks … and unicorn purses?)

Even a telephonic hearing would consume thinly-stretched court resources, Seeger wrote.

Moreover, he wrote in a separate minute entry, the plaintiff "proposes a bloated order that imposes extraordinary demands on third parties, including a wide array of technology companies and financial institutions. Plaintiff's proposed order would require immediate action, in a matter of days, from firms that have nothing to do with this case."

"In the meantime," he continued, "the country is in the midst of a crisis from the coronavirus, and it is not a good time to put significant demands on innocent third parties. … All of them undoubtedly have (more) pressing matters on their plates right now."

What truly seemed to irritate the judge wasn't the initial TRO request—it was that Hierl didn't take no for an answer, claiming that his client "will suffer an 'irreparable injury' if this court does not hold a hearing this week and immediately put a stop to the infringing unicorns and the knock-off elves," Seeger wrote.

After Seeger set the hearing schedule, Hierl filed a motion for reconsideration. But he didn't stop there. "Thirty minutes ago, this court learned that plaintiff filed yet another emergency motion," Seeger wrote, sounding more than a little peeved. "They teed it up in front of the designated emergency judge, and thus consumed the attention of the chief judge."

Bad move.

"The filing calls to mind the sage words of Elihu Root: 'About half of the practice of a decent lawyer is telling would-be clients that they are damned fools and should stop,'" Seeger wrote. "If there's ever a time when emergency motions should be limited to genuine emergencies, now's the time."

"To put it bluntly," he added in the minute entry, "Plaintiff's proposed order seems insensitive to others in the current environment. Simply put, trademark infringement is an important consideration, but so is the strain that the rest of country is facing, too. It is important to keep in perspective the costs and benefits of forcing everyone to drop what they're doing to stop the sale of knock-off unicorn products, in the midst of a pandemic."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Litigators of the Week: US Soccer and MLS Fend Off Claims They Conspired to Scuttle Rival League’s Prospect

Litigators of the (Past) Week: Tackling a $4.7 Billion Verdict Post-Trial for the NFL in 'Sunday Ticket' Antitrust Litigation

Take-Two's Pete Welch on 'Getting the Best Results While Getting in the Way the Least'

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Parties’ Reservation of Rights Defeats Attempt to Enforce Settlement in Principle

- 2ACC CLO Survey Waves Warning Flags for Boards

- 3States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 4Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 5Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250