What Spanish Flu-Era Contract Fights Tell Us about Pandemics and Contractual Performance

A historical parallel exists that potentially sheds light on the approach courts may adopt when interpreting contracts in light of an epidemic: the Spanish flu, writes Sidley Austin's global litigation co-head Yvette Ostolaza and associates Daniel Driscoll and Tayler Green.

April 01, 2020 at 04:05 PM

6 minute read

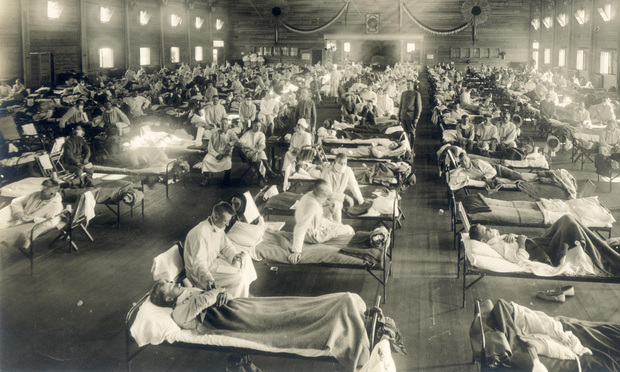

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, ill with Spanish flu at a hospital ward at Camp Funston in 1918.

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, ill with Spanish flu at a hospital ward at Camp Funston in 1918.

In light of the unprecedented scope and severity of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), governments and private entities across the globe are undertaking a variety of dramatic steps intended to halt the spread of the disease. These drastic changes have left businesses scrambling to manage compliance risk and to confront the realities of a dramatically altered economic environment.

Among other things, the pandemic's rapid spread has had a significant impact on the economic viability of a variety of long-term contractual arrangements and has left many businesses struggling to determine whether the impact of coronavirus suffices to excuse contractual performance. There are no simple solutions. Rather, the precise language of the contract at issue, along with applicable state law, is likely to dictate the risk of non-performance under present circumstances.

Setting these considerations aside, however, a historical parallel exists that potentially sheds light on the approach courts may adopt when interpreting contracts in light of an epidemic: the Spanish flu.

From 1918 to 1920, an epidemic of Spanish flu infected about a quarter of the world's population, killing tens of millions, including approximately 675,000 Americans. While the full scope of this outbreak has faded from public consciousness and is now largely overshadowed by the effects of World War I, the Spanish flu outbreak was devastating and marked perhaps the first truly global pandemic illness.

Like the current coronavirus outbreak, the Spanish flu also confronted businesses, individuals, and governmental entities across the world with quarantines and other disruptions, heightening the cost and difficulty of contractual compliance. Given these challenges, courts in this era struggled to balance the unexpected impact of the virus with the strict approach to contract performance enshrined by the common law.

While not a perfect analogue to present circumstances, the common law decisions from this era demonstrate the risk and uncertainty in asking courts to excuse performance, even under the most demanding of circumstances.

Unsurprisingly, the common law approach to contractual enforcement was notably harsh. As one New York court put it: "[I]f what [was] agreed to be done [was] possible and lawful the obligation or performance must be met. Difficulty or improbability of accomplishing the stipulated undertaking will not avail the obligor."

In line with this harsh approach, courts during the early part of the twentieth century were loath to excuse contractual compliance no matter how severe the circumstances. For example, in Phelps v. School District No. 109, the Supreme Court of Illinois rejected a school board's attempt to avoid paying a teacher's salary after local schools were closed as a result of a Spanish flu outbreak. The court explained that a school closure for public health reasons was not an "act of God . . . [but instead] was one of the contingencies which might have been provided against by the contract, but was not." Accordingly, the court determined that the school board should bear the loss for the unforeseen contingency of the pandemic and was required to meet its "unconditional" obligation of paying the teacher's salary during the closure.

Decisions from other courts are in accord; even when government regulation affected performance, performance was still required so long as the regulation did not render such performance literally illegal.

Still, depending on the terms of the contract issue, courts did sometimes find that disruptions caused by Spanish flu sufficed to suspend performance, at least temporarily. Indeed, in some cases, courts went so far as to specify that a pandemic sufficed to warrant setting aside a contract assuming that a party was rendered unable "to give or receive performance."

For example, in contrast to the Illinois decision discussed above, an Indiana appellate court excused a school from paying teacher salaries when a board of health official ordered school closures in response to the Spanish flu. The court explained that the board's order rendered performance impossible and, accordingly, "there could be no recovery for such time." Separately, a California appellate court ruled that a production slow-down based on a Spanish flu-related quarantine excused a delay in shipment because the terms of the contract authorized a delay, and appropriate notice was given to comply with contractual terms.

As reflected above, the fact that a global pandemic was almost certainly unforeseen by the contracting parties is not necessarily an acceptable excuse for breach. Nor is the fact that the effects of a pandemic are likely to include burdensome government regulation and a substantially increased cost of performance. Instead, setting aside doctrinal variance in state law, courts are likely to precisely analyze the contours of agreed contractual obligations and whether those obligations were, in fact, rendered impossible to satisfy based on changed circumstances.

While performance was not often excused, decisions related to the Spanish flu illustrate that courts have, at least at times, been willing to recognize the monumental impact of an epidemic as an excuse for contractual performance. As in all contract disputes, the language of the contract at issue plays a significant role in resolving any legal dispute, but, given the unprecedented nature of the coronavirus, a more creative approach is called for. The common law, while rigorous, provides another set of critical considerations when considering the costs and opportunities of non-performance.

Yvette Ostolaza is the managing partner of Sidley Austin's Dallas office, a member of the firm's management and executive committees, and co-head of Sidley's global litigation practice. Ms. Ostolaza can be reached at [email protected]. Daniel Driscoll and Tayler Green are Dallas associates in Sidley Austin's complex litigation and disputes practice.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

2024 Marked Growth On Top of Growth for Law Firm Litigation Practices. Is a Cooldown in the Offing for 2025?

Big Company Insiders See Technology-Related Disputes Teed Up for 2025

Litigation Leaders: Jason Leckerman of Ballard Spahr on Growing the Department by a Third Via Merger with Lane Powell

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1The Rise and Risks of Merchant Cash Advance Debt Relief Companies

- 2Ill. Class Action Claims Cannabis Companies Sell Products with Excessive THC Content

- 3Suboxone MDL Mostly Survives Initial Preemption Challenge

- 4Paul Hastings Hires Music Industry Practice Chair From Willkie in Los Angeles

- 5Global Software Firm Trying to Jump-Start Growth Hands CLO Post to 3-Time Legal Chief

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250