Daily Dicta: In Fight over Picasso Artwork, Lawyer Accuses Quinn Emanuel of Bullying Opponents—But He's the One Hit with Sanctions

Do Quinn Emanuel lawyers 'terrorize and intimidate their opponents'? Or simply make good on their threats?

May 03, 2020 at 10:17 PM

8 minute read

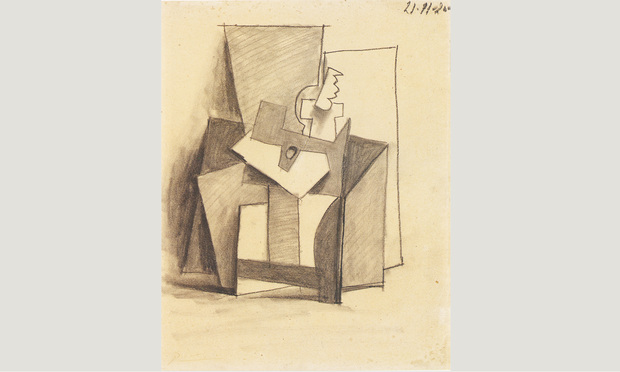

Pablo Picasso's Le Gueridon (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

Pablo Picasso's Le Gueridon (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

In full-page ads in The New York Times, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan in 2017 boasted, "Call us—and strike fear in the hearts of your opponents," and "In litigation, you get to choose who your opponents have to face in the courtroom. Why not choose the firm they fear most?"

To New York City solo practitioner Sidney Weiss, who is battling Quinn Emanuel partner Luke Nikas in a high-stakes fight over a work of art by Pablo Picasso, the ads show that firm lawyers lure clients by promising to "terrorize and intimidate their opponents," Weiss wrote in court papers. "No other factor, including legal knowledge and skill was mentioned."

Or … maybe Quinn Emanuel was just telling the truth?

Or … maybe Quinn Emanuel was just telling the truth?

Because Nikas made good on his warning to Weiss when a federal judge in Manhattan awarded Rule 11 sanctions, forcing Weiss personally to pay $20,000 and rejecting his client's RICO allegations.

"[T]he court believes the sanctions here are appropriately placed on plaintiff's counsel," wrote U.S. District Judge Katherine Polk Failla in the Southern District of New York on April 24, adding that she "recognizes the disparity in size between plaintiff's counsel and [Quinn Emanuel], and strives to sanction, without wholly bankrupting, plaintiff's counsel."

Weiss did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The underlying case is fascinating—and a reminder of how, despite the art world's genteel, chardonnay-sipping, high culture sheen, it also produces some gutter-worthy fights.

Nikas has carved out a leading art litigation practice—last year, he and Quinn Emanuel partner Maaren Shah were named Litigators of the Week for a pair wins—one of behalf of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts in defeating a copyright suit by noted photographer Lynn Goldsmith, and another for the Morgan Art Foundation in a heated battle with the estate of Robert Indiana—famous for his "LOVE" sculpture.

The fight over Picasso's "Le Gueridon," (pictured above) combines the hallmarks of many art disputes—"complicated statutory interpretation, RICO, fraud, ownership disputes, and the sprawling, international nature of the art business itself," Nikas said in an interview.

It began when Alejandro Domingo Malvar Egerique, a citizen and resident of Spain, bought Picasso's "Le Gueridon" (as well as "Composition avec Profil de Femme" by Fernand Leger) from Sotheby's in London in 2007.

Malvar hung the works in his home for eight years, but in 2015, he sent them to Ezra Chowaiki's gallery in New York on consignment.

If there's an obvious villain in this story, it's Chowaiki, who pleaded guilty to wire fraud in May of 2018. He was sentenced to 18 months in prison and ordered to pay up to $12.9 million in restitution.

Chowaiki was supposed to sell the artwork on Malvar's behalf.

That didn't happen. Instead, Chowaiki borrowed $300,000 from one of Nikas' clients in the suit, boutique investment manager Piedmont Capital—which specializes in alternative asset classes, including artwork—and used "Le Gueridon" as well as two other works (which belonged to non-parties in the case) as collateral. The collateral art was allegedly worth closer to $1 million.

According to Nikas, Chowaiki defaulted on the loan but failed to convey undisputed title to the artworks to Piedmont as promised.

On October 4, 2017, Nikas' clients picked up the Picasso from Chowaiki's gallery and sent it to Europe, according to the judge's decision. The piece went from Italy to Switzerland to London to Switzerland, and was also exhibited for 10 weeks in a gallery in Milan. It's not entirely clear from the court papers where "Le Gueridon" is now, though Nikas is adamant that his clients don't have it.

There are certainly reasons to find Piedmont's loan to Chowaiki questionable. It was for 30 days, with a whopping $50,000 interest—equal to an annual rate of 202%.

Still, Nikas argues that his clients—Piedmont and its principal Avichai Rosen, along with Rosen's wife Linda Benrimon and his father-in-law, David Benrimon, who together run the David Benrimon Fine Art gallery—are "victims of Chowaiki's crimes," just like Malvar and others who were defrauded.

"Chowaiki stole the $300,000 from Piedmont, and Piedmont eventually obtained rights to artworks in which many other similarly situated victims of Chowaiki also made competing claims of ownership," Nikas wrote.

But Malvar in his complaint flat-out rejected the notion that the Benrimons were also victims of Chowaiki. Instead, he alleged they were in cahoots, asserting RICO and state law claims against both the Benrimons and Chowaiki.

The loan was a sham, Malvar alleged, "designed to conceal that all the defendants were operating together, and that each of them knew the works of art subject to these documents could not be lawfully assigned, sold, or hypothecated."

David Benrimon and his gallery were the true purchasers of the Picasso, the complaint alleges, buying the work "at a deep discount, knowing [it] to be stolen or acquired and sold falsely," Weiss wrote on behalf of his client.

The high-interest loan, he continued, "was not intended by anyone to be paid, because the $300,000 was a purchase of property known by all defendants to be stolen."

Those are some big accusations. But where was the proof?

"The complaint in this case is both disjointed and replete with conclusory allegations," Failla wrote in dismissing the RICO allegations with prejudice. "[T]he court concludes that the predicate acts here are far too disparate and inadequately pleaded to constitute a pattern of racketeering activity."

"Plaintiff has pleaded no facts supporting his oft-repeated contention that the Benrimon defendants knew that the artwork pledged as collateral was stolen," the judge found.

Malvar faulted the Benrimons for doing business with Chowaiki, arguing that they should have known the gallery owner had "a court-documented history of selling and pledging stolen artwork that he had no right to sell or pledge." But if so, Failla pointed out, this "should have indicated the same to plaintiff, who nevertheless chose to consign his artwork with Chowaiki."

"Relatedly, the court rejects plaintiff's claim that the Benrimon defendants are liable under RICO for failing to predict that, some time off in the future, Chowaiki would be arrested and charged with wire fraud," she continued.

"The reality of the situation is that Chowaiki and the Benrimon defendants were both participants in an elite, but opaque, fine art market. That Chowaiki and the Benrimon defendants engaged in a transaction in which Chowaiki posted collateral that was stolen does not, in and of itself, give rise to the inference that the Benrimon defendants were in on the fraud," the judge concluded.

Failla also dismissed state law fraud claims against the Benrimons, leaving only the claims for conversion and replevin of the artwork.

In imposing sanctions against Weiss, Failla found that most of the RICO claims, while far-fetched, were not so frivolous as to be punishable. But she ruled that the four counts alleging unlawful debt collection crossed the line.

"[T]he court is in complete agreement with the Benrimon defendants that the unlawful debt collection claims against them are particularly egregious, and that plaintiff's persistence in advancing these claims for which he has no articulable legal or factual basis is objectively unreasonable," she wrote.

She also objected to the accusation that the Benrimon defendants committed a fraud on the criminal court, finding it "completely unwarranted. Plaintiff's failure to correct this allegation evinces a carelessness with lodging very serious accusations that greatly troubles the court."

As for fining Weiss instead of his client, Failla wrote that it "was plaintiff's counsel who was warned at the July 29, 2019 pre-motion conference that a single allegation of a usurious loan would not suffice to plead such RICO claims adequately. And it was plaintiff's counsel who told the court that he would remedy such deficiency in the amended complaint, yet failed to do so."

She added, "The court acknowledges that the $20,000 sanction imposed will not fully compensate the Benrimon defendants for the fees and costs expended on the unlawful debt collection issue, but it will fully punish plaintiff's counsel for his conduct in accordance with the letter and spirit of Rule 11."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Litigators of the Week: US Soccer and MLS Fend Off Claims They Conspired to Scuttle Rival League’s Prospect

Litigators of the (Past) Week: Tackling a $4.7 Billion Verdict Post-Trial for the NFL in 'Sunday Ticket' Antitrust Litigation

Take-Two's Pete Welch on 'Getting the Best Results While Getting in the Way the Least'

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1ACC CLO Survey Waves Warning Flags for Boards

- 2States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 3Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 4Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 5Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250