Daily Dicta: Defending the Indefensible (Or Not)

Our justice system is premised on the notion that even the most awful human beings accused of the most heinous crimes are entitled to a legal defense. Whoever defends Chauvin is sure to be threatened and vilified. But that lawyer will also be brave—braver (ahem) than certain Am Law 100 firms.

June 01, 2020 at 09:59 PM

5 minute read

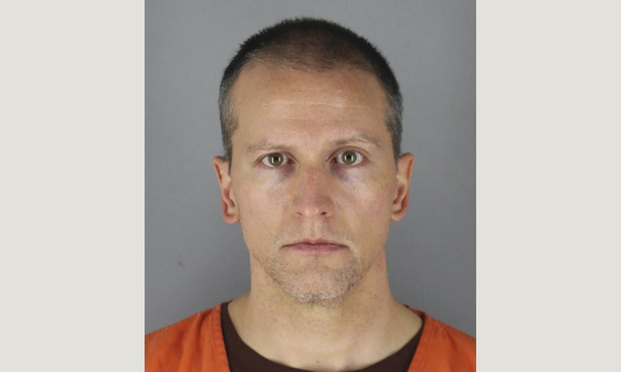

This May 31, 2020 photo provided by the Hennepin County Sheriff shows Derek Chauvin, who was arrested Friday, May 29, in the Memorial Day death of George Floyd. Chauvin was charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter after a shocking video of him kneeling for several minutes on the neck of Floyd, a black man, set off a wave of protests across the country. (Hennepin County Sheriff via AP)

This May 31, 2020 photo provided by the Hennepin County Sheriff shows Derek Chauvin, who was arrested Friday, May 29, in the Memorial Day death of George Floyd. Chauvin was charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter after a shocking video of him kneeling for several minutes on the neck of Floyd, a black man, set off a wave of protests across the country. (Hennepin County Sheriff via AP)

Our justice system is premised on the notion that even the most awful human beings accused of the most heinous crimes are entitled to a legal defense.

Derek Chauvin seems to be pushing the limit.

The now-fired Minneapolis police officer has been charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter in the death of George Floyd—a crime that has set America aflame. And some poor lawyer will have to defend him.

How unappealing is the assignment? Here's one measure. I reached out on Monday to white collar defenders and former prosecutors at Kirkland & Ellis; Hogan Lovells; Latham & Watkins; Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom; Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher; O'Melveny & Myers; Mayer Brown; Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe; Boies Schiller Flexner; Morgan, Lewis & Bockius; Jenner & Block; King & Spalding; Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan; Kasowitz Benson Torres; Sullivan & Cromwell; Sidley Austin; Covington & Burling and Steptoe & Johnson. I also hit up PR agencies that work with multiple law firms, and asked them all the same thing: What in theory might Chauvin's defense entail?

"I'm looking for any general thoughts on how his lawyer might proceed. How do you make sure a client gets a fair trial when they are so widely despised? How could you pick a jury? What personal risks might a defense lawyer face in taking on such a case? Is it worth it?" I asked.

"I'm looking for any general thoughts on how his lawyer might proceed. How do you make sure a client gets a fair trial when they are so widely despised? How could you pick a jury? What personal risks might a defense lawyer face in taking on such a case? Is it worth it?" I asked.

And across the board, these elite firms, which together employ more than 22,000 of the best lawyers in the country, which pride themselves on their independence and toughness, their willingness to tackle difficult problems?

They all declined comment or didn't respond. Every single one of them.

In two decades of legal reporting I've never encountered such reticence—not with such a broad question posed to so many lawyers at so many firms.

Of course, I understand there's no marketing advantage to being quoted on this topic. It's not like being asked to opine on a Supreme Court decision that could directly impact your clients, or weighing in on new developments in ERISA.

But c'mon. I do think it's valid to wonder how in the world Chauvin's defense lawyer, whoever that may be, might proceed. The fact that none of you would touch it is a sign that representing him will be uniquely difficult.

Non-lawyers might say, 'Good. Chauvin doesn't deserve a fair trial. He wasn't fair when he kept his knee on George Floyd's neck for nearly nine minutes, ignoring his pleas that he couldn't breathe."

Which is true. But we all also know that's not how our system works—and in fact, it's why our system is just. Even if it means monsters get lawyers.

A few years ago, I spent several hours interviewing a now-retired public defender named Barry Collins for a book project that never came to fruition.

Collins defended Richard Allen Davis, who in 1993 spied a 12-year-old girl named Polly Klaas buying popsicles at a store in Petaluma, California. He followed her home, lay in wait, and then kidnapped her from her bedroom in the middle of the night as Polly's two friends, who were sleeping over, looked on in horror.

The case was huge news at the time. When Davis was arrested eight weeks later, he confessed to strangling Polly to death and dumping her body in a blackberry briar.

Collins got the job of defending him—it didn't go well, Davis got the death penalty—but the lawyer's thoughts on the experience may resonate with whoever defends Chauvin.

"If you're a true public defender, what is the ultimate task you can get in your career? Representing someone like Richard Allen Davis. It's a whole different world, one that even other public defenders can't relate to," Collins told me.

"I have an analogy," he continued. It's like being a doctor in a war zone treating wounded combatants. "You're not supposed to worry if the guy is an enemy private or a general on the U.S. side … You do the job the same way. In a way, that's what being a public defender is all about," he said. "When you handle a high-profile case for a terrible crime, you have to have a certain kind of DNA. You have to be able to do it without regard for what other people think."

Whoever defends Chauvin is sure to be threatened and vilified. But that lawyer will also be brave—braver (ahem) than certain Am Law 100 firms.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

2024 Marked Growth On Top of Growth for Law Firm Litigation Practices. Is a Cooldown in the Offing for 2025?

Big Company Insiders See Technology-Related Disputes Teed Up for 2025

Litigation Leaders: Jason Leckerman of Ballard Spahr on Growing the Department by a Third Via Merger with Lane Powell

Law Firms Mentioned

- Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan

- Morgan, Lewis & Bockius

- Hogan Lovells

- Steptoe & Johnson LLP

- Kasowitz Benson Torres

- Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP

- Kirkland & Ellis

- Covington & Burling

- Sullivan & Cromwell LLP

- Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher

- Latham & Watkins

- Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe

- Boies Schiller Flexner

- Sidley Austin

- Mayer Brown

- O'Melveny & Myers

- King & Spalding

- Jenner & Block

Trending Stories

- 1Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

- 2California Court Denies Apple's Motion to Strike Allegations in Gender Bias Class Action

- 3US DOJ Threatens to Prosecute Local Officials Who Don't Aid Immigration Enforcement

- 4Kirkland Is Entering a New Market. Will Its Rates Get a Warm Welcome?

- 5African Law Firm Investigated Over ‘AI-Generated’ Case References

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250