'Wise Lawyers Keep Accurate Time Records': Calif. Court Denies Attorney's Bid for More Fees

Attorney Michael Traylor was seeking $308,000 for early work on a case that ultimately yielded a $7 million settlement. The Second District Court of Appeal found that Traylor hadn't handed over his file to lawyers who took over the case and had submitted three separate accounts of time spent on the matter.

June 11, 2020 at 04:58 PM

4 minute read

The original version of this story was published on The Recorder

Lights flashing atop a police car. (Photo: Shutterstock)

Lights flashing atop a police car. (Photo: Shutterstock)

A California appellate court has turned down a request from a lawyer seeking $308,000 in attorney fees for his initial representation of the family of a man shot and killed by Los Angeles County sheriff's department officers in 2016.

The Second District Court of Appeal on Wednesday affirmed a trial court decision granting Los Angeles attorney Michael Traylor just $17,325 from the $7 million settlement that lawyers who took over the case from him reached to settle the wrongful death and civil rights claims. The court found that Traylor hadn't handed over his files to the new lawyers and had submitted three separate accounts of time spent on the matter. In publishing the decision, the court noted it wanted to highlight that "contemporaneous time records" are the best evidence of an attorney's work.

"They are not indispensable, but they eclipse other proofs," wrote Second District Justice Shepard Wiley Jr. "Lawyers know this better than anyone. They might heed what they know."

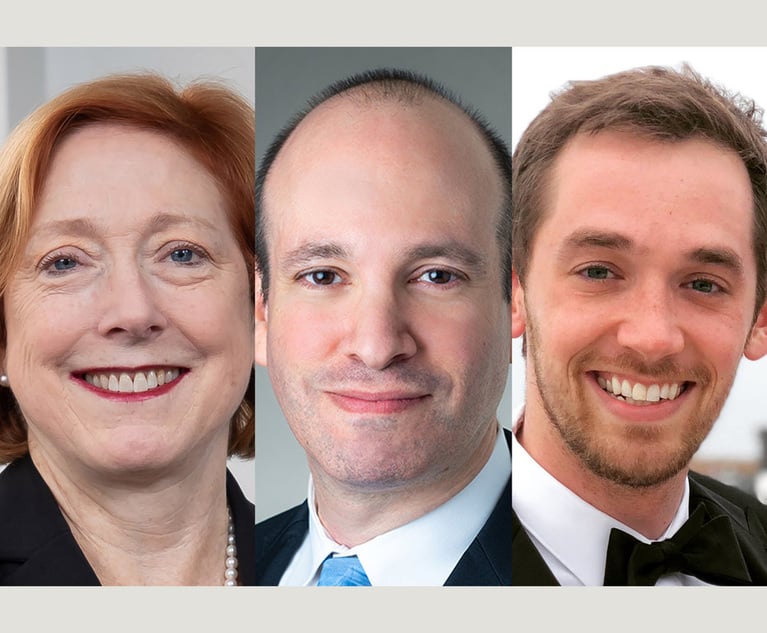

In the underlying case, John Sweeney of The Sweeney Firm and Steven Glickman of Glickman & Glickman, both in Beverly Hills, ultimately took on the case for the family of Donta Taylor, who was shot and killed in a foot chase with two police deputies in 2016. The deputies claimed that Taylor had a handgun, but no weapon was found, and the county ultimately agreed in 2018 to pay $7 million in a settlement with Taylor's family.

Traylor, who had represented the family for a month following the shooting, filed an attorney's lien on the settlement. According to Wednesday's decision, Traylor gave Sweeney two invoices in October of that year, one for Taylor's father and one for his fiancee for his 2016 work on the case, both of which misspelled Donta Taylor's name. Traylor ultimately submitted three separate billing records claiming that he worked "130.0, 180.00, and 200.0 hours" on the case. The court referred to the numbers as "curiously round."

"Witnesses can be prone to bias when their own paychecks are at stake," wrote Wiley, joined in the decision by Justices Elizabeth Grimes and Maria Stratton. "And every lawyer who has kept time sheets knows delays in recordkeeping diminish accuracy. If you are a month late, it is hard to reconstruct a bygone day in six-minute intervals. Now increase the delay to two years. Perform this thought experiment: what were you doing two years ago today, down to six-minute intervals? These two risks aggravate each other: unless you kept detailed contemporaneous records according to some reliable method, common experience will lead observers to regard your tardy and self-serving six-minute claims as largely fictional."

"For this reason, wise lawyers keep accurate time records," Wiley concluded.

Reached by email Thursday, Traylor said he intended to file a petition for rehearing. Traylor said that this was not an hourly billing case and that California precedent allows for reasonable estimates in contingency fee cases and that Sweeney and Glickman had submitted varying estimates of their time in the case as well.

In a phone interview Thursday, Glickman said that he agrees that contingency lawyers should be compensated for their overall contributions to the success of a case. But, he added, Traylor hadn't provided any case files of witness interviews or "anything of substance" to substantiate his work on the case.

Glickman said that Traylor deserved some compensation for helping the family navigate an incredibly difficult time, but that it was hard to justify attorney fees for substantive work "when he never handed over any of his work product."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

MoFo Associate Sees a Familiar Face During Her First Appellate Argument: Justice Breyer

Amid the Tragedy of the L.A. Fires, a Lesson on the Value of Good Neighbors

Litigators of the Week: Shortly After Name Partner Kathleen Sullivan’s Retirement, Quinn Emanuel Scores Appellate Win for Vimeo

Trending Stories

- 1Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

- 2California Court Denies Apple's Motion to Strike Allegations in Gender Bias Class Action

- 3US DOJ Threatens to Prosecute Local Officials Who Don't Aid Immigration Enforcement

- 4Kirkland Is Entering a New Market. Will Its Rates Get a Warm Welcome?

- 5African Law Firm Investigated Over ‘AI-Generated’ Case References

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250