Daily Dicta: This Case Looked Unwinnable. How a Kirkland Team Won It Anyway

Lesser lawyers might have said the case was hopeless. But not a team from Kirkland led by Mike Williams and Susan Davies, who just got provisions of a 48-year-old law declared unconstitutional.

June 23, 2020 at 01:17 AM

6 minute read

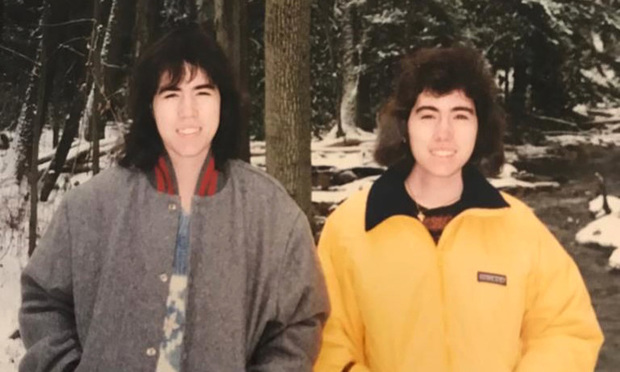

Katrina and Leslie Schaller

Katrina and Leslie Schaller

It would be hard to script a better hypothetical: Two sisters, 50-year-old identical twins, both born and raised in Pennsylvania, both suffering from myotonic dystrophy, a degenerative disorder affecting muscle function and mental processing.

Leslie Schaller still lives in Pennsylvania and gets a $755 Supplemental Security Income, or SSI, check each month after she was deemed disabled. With this money, she is able to lead a full and independent life.

But her twin Katrina lives in Guam—she moved there permanently in 2008 to live with their other sister, who cares for her.

Because Guam is an unincorporated United States territory, Katrina is not entitled to receive SSI benefits. Does this law—in place since 1972—run afoul of the equal protection clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution?

Thanks to some extraordinary lawyering by a pro bono team from Kirkland & Ellis led by Mike Williams and Susan Davies, a federal judge in Guam said yes. Siding with Katrina, Chief U.S. District Judge Frances Tydingco-Gatewood ruled on summary judgment that "the equal protection guarantees of the Fifth Amendment forbid the arbitrary denial of SSI benefits to residents of Guam."

If the ruling stands, it will mean about 24,000 people in Guam will be able to receive potentially life-changing disability benefits.

It's an outcome few might have predicted six years ago when Rodney Jacob, a leading lawyer in Guam and name partner at Calvo, Fisher & Jacob, first approached Williams about the case. The biggest obstacle? Two unfavorable U.S. Supreme Court decisions that seemed directly on point.

In Califano v. Gautier Torres, a man who received SSI benefits while living in Connecticut had them discontinued when he moved to Puerto Rico. He sued in U.S. District Court in Puerto Rico, claiming that the exclusion of Puerto Rico from the SSI program was unconstitutional.

In Califano v. Gautier Torres, a man who received SSI benefits while living in Connecticut had them discontinued when he moved to Puerto Rico. He sued in U.S. District Court in Puerto Rico, claiming that the exclusion of Puerto Rico from the SSI program was unconstitutional.

In its 1978 decision, the Supreme Court ruled against him, noting that "Congress has the power to treat Puerto Rico differently, and that every federal program does not have to be extended to it."

So that wasn't helpful.

Two years later, the high court rebuffed a similar suit—a class action involving payment amounts under the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program.

The Supreme Court pointed out that "Puerto Rican residents do not contribute to the federal treasury; the cost of treating Puerto Rico as a state under the statute would be high; and greater benefits could disrupt the Puerto Rican economy."

All of which could also be said about Guam, the Social Security Administration argued in Katrina Schaller's case.

"Binding Supreme Court precedent makes clear that Congress can pass economic and social welfare legislation affecting U.S. Territories so long as it has a rational basis for its actions," wrote Daniel Riess, a trial lawyer in the Justice Department's Civil Division.

"Here," he continued, "the legislation at issue clearly satisfies rational-basis review, as residents of Guam do not pay federal income tax, which funds the SSI program; because the increased cost to the federal treasury of extending SSI benefits to residents of Guam would be very substantial, especially in light of the fact that Guam residents are exempted from paying federal income tax; and because Congress could have reasonably concluded that extending SSI benefits eligibility to Guam residents could result in appreciable inflationary pressure."

Lesser lawyers might have said Katrina's case was hopeless. But not team Kirkland, which in addition to Williams and Davies also included partner Beth Dalmut and associates Julia Choi, Katherine Epstein, Emily Merki Long, Luke McGuire, Paul Quincy and Paul Suitter.

Williams, a well-known trial lawyer and appellate advocate who also serves on Kirkland's firmwide pro bono management committee, was quick in an interview to credit Davies, whom he called "a certifiable legal genius," for figuring out a winning approach.

The key? The Northern Mariana Islands—a chain of 14 islands with a population of 53,883. A mere 60 miles north of Guam, the islands have been a U.S. commonwealth since 1975.

By contrast, Guam has been a U.S. territory since 1898 and its residents and have enjoyed U.S. citizenship since 1950.

There's no question Guam has a deeper relationship with the United States, Williams said. And yet, residents of the Northern Mariana Islands are entitled to receive SSI benefits while those in Guam are not.

How is that fair?

"Our argument wasn't just Guam versus the United States, it was Guam versus the Northern Mariana Islands," Williams told me.

By re-focusing the case on the disparate treatment of Guam and the islands, the Kirkland team was able to argue that reliance on the unfavorable Supreme Court decisions was misplaced.

The judge bought it.

"While Guam's tax status might explain why it is treated differently from the fifty States and the District of Columbia, it does not justify the distinction in treatment between Guam and the [Northern Mariana Islands] with regard to SSI benefits," Tydingco-Gatewood wrote.

Nor would extending SSI benefits to Guam break the U.S. Treasury, she found. Costs estimates range from $17 million to $175 million—or 0.03% to 0.3%. of the SSI program's $54 billion expenditures in 2017.

"As plaintiff notes, such a minimal increase in cost does not qualify as 'extremely great' so as to justify the unequal treatment of eligible citizens residing in Guam," she wrote.

As for the economic disruption argument, well, that's just stupid.

Guam residents in need can already get SNAP and Medicare benefits, "and there is no evidence to suggest that the influx of these federal funds have negatively impacted Guam's economy. To the contrary, these public assistance dollars from the federal government have benefitted Guam's economy," the judge wrote. "[I]t is irrational to conclude that Guam's economy would be disrupted if it were included in the SSI program."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Litigators of the Week: A Knockout Blow to Latest FCC Net Neutrality Rules After ‘Loper Bright’

An ‘Indiana Jones Moment’: Mayer Brown’s John Nadolenco and Kelly Kramer on the 10-Year Legal Saga of the Bahia Emerald

Litigators of the Week: A Win for Homeless Veterans On the VA's West LA Campus

'The Most Peculiar Federal Court in the Country' Comes to Berkeley Law

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Contract Technology Provider LegalOn Launches AI-powered Playbook Tool

- 2Court of Appeals Provides Comfort to Land Use Litigants Through the Relation Back Doctrine

- 3Amid the Tragedy of the L.A. Fires, a Lesson on the Value of Good Neighbors

- 4Democracy in Focus: New York State Court of Appeals Year in Review

- 5In Vape Case, A Debate Over Forum Shopping

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250