12 Masked Strangers Brought Together To Do Justice. A Summer Superhero Flick? Nope, Just a Jury Trial

On Monday, after COVID-19 forced a three-and-a-half-month break in a federal criminal jury pending before U.S. District Judge William Alsup in San Francisco, 15 of the 16 original jurors and alternates showed up to resume proceedings.

July 06, 2020 at 11:18 PM

6 minute read

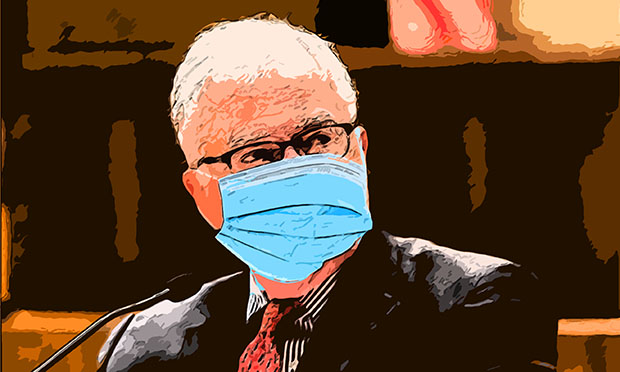

Judge William Alsup, of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. (Photo illustration: Jason Doiy/ALM.)

Judge William Alsup, of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. (Photo illustration: Jason Doiy/ALM.)

Juries continue to mystify me. But sometimes in delightful and inspiring sorts of ways.

On Monday, after COVID-19 forced a three-and-a-half-month break in a federal criminal jury pending before U.S. District Judge William Alsup in San Francisco, 15 of the 16 original jurors and alternates showed up to resume proceedings.

The only no-show: A woman whose husband worked alongside someone who recently tested positive for the virus. Even she had Alsup's blessing for her absence since she and her husband were told to quarantine by their doctor and were unable to procure a test until Tuesday.

The turnout—and the fact that only three of the remaining 15 jurors raised hardships Monday that necessitated their dismissal—both surprised and impressed federal prosecutors Michelle Kane and Katherine Wawrzyniak and defense lawyers Adam Gasner and Valery Nechay, who represent Yevgeniy Nikulin, a Russian man being accused at trial of hacking LinkedIn, Dropbox and Formspring.

Alsup, who has repeatedly tried to get the trial back on track, has openly lamented at prior hearings away from the jury that Nikulin has been in pretrial detention for nearly four years—a stretch that could be longer than any sentence Nikulin might get should he be found guilty. Given the circumstances, the lawyers had stipulated to move forward with as few as six jurors, if necessary.

By the way, I know the lawyers were impressed with the jurors in the Nikulin case not because they told me, but because I was tuned into the trial's resumption via a Zoom videoconference set up by the court to ensure that Nikulin received a "public" trial. The microphones on counsels' tables captured some of the shoptalk that takes place between proceedings that I normally am left to guess about when reporting from my typical seat behind the bar in the gallery.

On Monday, my usual seats were occupied by jurors. With room for just four people to sit in the jury box under the court's new social distancing guidelines, a majority of the jurors were spaced out in the much less cushy, wooden-backed gallery pews. Once the jury was pared down to the 12 remaining individuals—including one woman who has a long-scheduled vacation set for next week who might be allowed out of jury duty should proceedings push past Friday—Alsup inquired if anyone in the gallery had a bad back and might need to move into the cushioned jury box chairs. When two jurors raised their hands asking to be moved, one juror originally assigned to what I'll call "the luxury box" for the time being volunteered to move out to the more rigid pews.

"Isn't that just great? Isn't that way our country should work?" said Alsup after the volunteer stepped forward.

Before the day got underway, Alsup lined out all the precautions the Northern District has taken to maintain the safety of jurors, court personnel, lawyers, and witnesses. He assured jurors that the ventilation system in the Phillip Burton Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse only takes in outside air and does not recycle air within the 21-story building. Alsup also noted that the court is only allowing one trial to move forward per courthouse. Nikulin's trial and another starting in the court's Oakland location were the first to push off under the court's new COVID-19 guidelines.

Other precautions include that all jurors, lawyers and personnel must wear masks at all times in the courthouse. Witnesses are the lone exception to the mask mandate. They must wear masks as they enter and exit the courtroom, but the witness stand has been encased with plexiglass so jurors can see a witness's face and demeanor during testimony. "At first, it looks kind of strange, but I promise you after a few hours you'll get used to it and it won't interfere with our ability to do our job," Alsup told jurors.

(Sidenote: That image of Alsup in a mask atop this column is a photo illustration put together by my colleague Jason Doiy. Per court rules, we were not allowed to take a screenshot or record any of the Zoom proceedings. Trial is set to resume this morning, you can access the link for today's proceedings here.)

The courtroom will be cleaned and sanitized each day, Alsup said, and the court has hand sanitizer and wipes on hand. The lawyers were asked to handle examinations and arguments from counsel's table and were limited to having two people sit at the table at a time—a bit of an awkward set up for the prosecutors who needed their paralegal at the table to present audio-visual evidence.

Kane took a break from her 15-minute reopening summary of what had happened in the trial before the extended break to acknowledge getting the trial back on track will make for some awkward logistical dances at times. "We're figuring this out as we go," she said.

I think that goes for all of us.

On a related note, I can strangely think of no better time to start work as a national litigation columnist. The changes forced by the pandemic have put many more proceedings like Monday's at my fingertips. So, how does what's going on in Alsup's courtroom compare with what's going on in your neck of the woods? And are the other proceedings open to anyone with a phone line or solid WiFi connection that you think might make interesting column fodder. I'm all ears at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Litigators of the Week: A Knockout Blow to Latest FCC Net Neutrality Rules After ‘Loper Bright’

Litigators of the Week: After a 74-Day Trial, Shook Fends Off Claims From Artist’s Heirs Against UMB Bank

Trending Stories

- 1New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 2No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 3Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 4Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 5Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250