Judges Get Real About Prospects for Civil Jury Trials: 'It's Just Going to Get Worse'

You want a jury trial in your civil case? Get in line.

July 22, 2020 at 07:30 AM

6 minute read

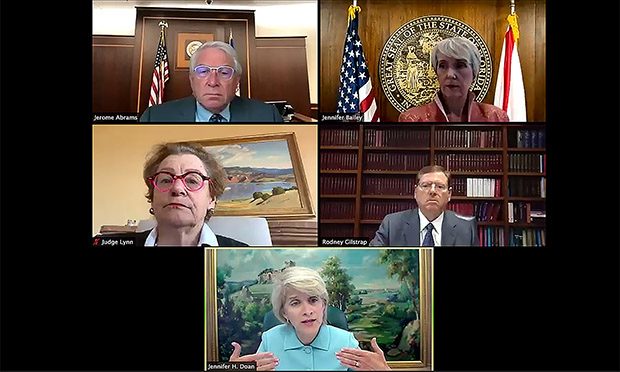

Jury Trials in the Age of Pandemics view from the bench panelists: Moderator Jennifer H. Doan; Hon. Jerome B. Abrams First Judicial District; Hon. Jennifer D. Bailey Administrative Judge, Circuit Civil Division Eleventh Judicial Circuit; Hon. J. Rodney Gilstrap Chief District Judge United States District Court Eastern District of Texas and Hon. Barbara M.G. Lynn Chief District Judge United States District Court Northern District of Texas. (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

Jury Trials in the Age of Pandemics view from the bench panelists: Moderator Jennifer H. Doan; Hon. Jerome B. Abrams First Judicial District; Hon. Jennifer D. Bailey Administrative Judge, Circuit Civil Division Eleventh Judicial Circuit; Hon. J. Rodney Gilstrap Chief District Judge United States District Court Eastern District of Texas and Hon. Barbara M.G. Lynn Chief District Judge United States District Court Northern District of Texas. (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

You want a jury trial in your civil case?

Get in line.

That's what I took away from a panel discussion between four judges from across the country who spoke as part of a day-long, virtual program put on Tuesday by the American Board of Trial Advocates titled "Jury Trials in the Age of Pandemics."

U.S. Chief District Judge Barbara Lynn of the Northern District of Texas, U.S. Chief District Judge Rodney Gilstrap of the Eastern District of Texas, Administrative Judge Jennifer Bailey of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit in Miami-Dade County, Florida, and Judge Jerome Abrams of the First Judicial District in Hastings, Minnesota told more than 700 attendees tuning in via a Zoom video conference about the steps their courts are taking to conduct jury trials in a manner that's safe for court participants and jurors. Those measures, which require lots of space and tons of dedicated resources for cleaning and disinfecting facilities, are creating bottleneck issues, compounded by Constitutional mandates to keep criminal trials moving.

"I think the parties really need to reevaluate where they are," said Bailey, who handles a complex business litigation docket out of Miami. "The truth of the matter is, I'm just being blunt folks, you're not all going to get jury trials. We're going to have to ration jury trials over the next year-and-a-half or two years," she said. Bailey said that she expects a "tsunami of cases" coming into her state courts on matters including business disruption, breach of contract, foreclosure, and eviction given the economic climate.

"Your cases are going to be struggling for oxygen with those cases," she said. Anyone playing the waiting game hoping to go to trial in two years could be looking at a potential four-year delay, she said.

Gilstrap, who oversees a docket stuffed with high stakes patent litigation matters in the Eastern District of Texas, said that his federal court is looking at "the same kind of tsunami."

"It's just going to get worse," Gilstrap said. "Bear with the judges," he pleaded. "We are all doing the best we can. We are trying to be fair to both sides, and we are dealing with issues that have never come up before."

His caseload often involves parties, witnesses, and experts from around the globe, and bringing them altogether for trial in rural East Texas has become impossible with international travel lockdowns. That's not to mention the fact that his courthouse in Marshall lacks a jury assembly room or any additional courtrooms to allow lawyers, participants and the public to easily spread out.

"Nobody knows how we go forward and when we go forward, but when we do, it's probably going to require some variations on what's been traditionally done," he said. "Stay tuned and see what happens."

Lynn, whose court in Dallas held a jury trial last month with jurors masked and everyone socially distanced in a single-defendant, one-count criminal case, said that civil lawyers should think seriously about embracing virtual proceedings.

"My advice is to be creative and not wax nostalgic for the way things used to be, because I don't know when the way things used to be will come back again," she said. "Be creative about where, how and when you can try cases."

Lynn said that she's contemplating holding court outdoors "when it isn't so darn hot as it is in Texas right now" in the quadrangle of the local law school where she can hook up electronics and maintain a safe distance between court participants better than in the courthouse. "If you don't want to get nosed out, try to come up with another way that we can hear your cases in a timely way," she said.

Abrams, the Minnesota state court judge, encouraged advocates to be "terse" and "pithy" going forward. He encouraged the lawyers in the audience to "think about what's really important."

"Focus on what you really need fact-finder to decide," he said. "We're prevailing on people's time in a different way now."

In case you're a civil trial lawyer looking for some nuggets of hope to temper these calls for patience and portraits of jurisprudential doom-and-gloom, here are a couple.

Lynn not only pulled off her criminal trial last month, she did it with a diverse jury which included 5 Black and 2 Hispanic jurors. "I was very skeptical that we could get A.) a jury at all and B.) a fair cross-section of our community, and I was wrong," she said.

Bailey likewise had good news about her court's ability to seat a jury with COVID-19 cases on the uptick in South Florida. But by conducting voir dire via Zoom, then bringing the six jurors and two alternates to the courthouse for proceedings, her court recently seated a jury in an insurance case. "In the middle of a crushing surge in the last 10 days we got a jury in Miami-Dade County," she said. "You can get a jury during COVID. You can get a jury during a surge."

Abrams, meanwhile, pointed out that his court was able to keep moving on 45- to-50% of its typical civil caseload by doing more online and conducting virtual bench trials. Getting exhibits in a format that everyone can access them, he said, has required some extra prep work from the lawyers.

But, he added, "The bench trials are going just fine."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Some Thoughts on What It Takes to Connect With Millennial Jurors

Litigators of the Week: A Knockout Blow to Latest FCC Net Neutrality Rules After ‘Loper Bright’

Trending Stories

- 1Gunderson Dettmer Opens Atlanta Office With 3 Partners From Morris Manning

- 2Decision of the Day: Court Holds Accident with Post Driver Was 'Bizarre Occurrence,' Dismisses Action Brought Under Labor Law §240

- 3Judge Recommends Disbarment for Attorney Who Plotted to Hack Judge's Email, Phone

- 4Two Wilkinson Stekloff Associates Among Victims of DC Plane Crash

- 5Two More Victims Alleged in New Sean Combs Sex Trafficking Indictment

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250