Memo to Trump: What Not to Expect From Robert Mueller

A letter of exoneration? White-collar defense lawyers say it would be outside the typical course of things for a prosecutor to put anything in writing that would absolve someone of any wrongdoing.

December 19, 2017 at 07:11 PM

5 minute read

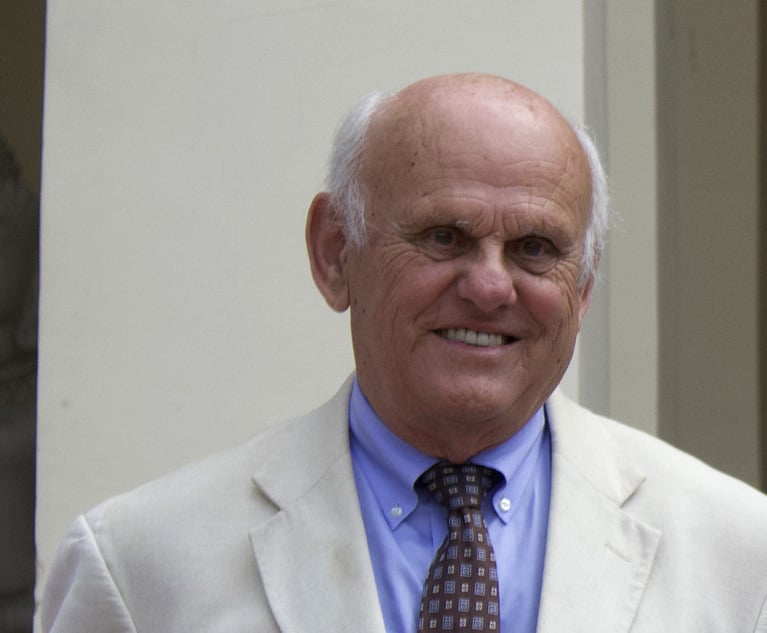

President Donald Trump. Credit: Shealah Craighead / White House

President Donald Trump. Credit: Shealah Craighead / White House The federal investigation into Russia's interference in the U.S. presidential election and what the Trump campaign team knew, or didn't know, is sure to stretch for weeks—if not many more months. That could be unsettling for anyone who might be in the orbit of Robert Mueller and his special counsel's office prosecutors.

President Donald Trump has told associates, according to a CNN report, that he expects some sort of all-clear from Mueller, something he can show off that says he has done nothing wrong. CNN characterized this document as a “letter of exoneration.”

But Trump may not want to get his hopes up. Several white-collar defense lawyers in Washington said it would be outside the typical course of things for a prosecutor to put anything in writing that would absolve someone of any wrongdoing.

“That's just not normal procedure whatsoever,” said Mayer Brown partner Kelly Kramer, co-leader of the firm's white-collar defense and compliance practice. He added: “I've never heard of an exoneration letter. The only way I can see to get to 'exoneration' here is through a report to Congress, which of course is not typically how the DOJ does business.”

Federal prosecutors have discretion to write a “declination” memo that tells a target he or she is no longer under investigation, or that the investigation has closed. But these memos are rare, and there's nothing that compels a prosecutor to write one in the first place, several white-collar defense lawyers said.

In some cases, an individual or company will learn through an informal call that an investigation has been closed. Sometimes, that notification will never come.

“Silence is golden,” said one lawyer.

Declination memos, when they do get sent, come in a matter-of-fact style. They give the status of an investigation without going so far as to assert a onetime target is innocent. Several lawyers said they've never seen a declination memo longer than a single page.

”Exoneration is not a concept that exists in the panoply of weapons and communications from the Department of Justice,” said Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher partner Joel M. Cohen, a former federal prosecutor who is now co-leader of his firm's white-collar and investigations group. “You can only be exonerated after you've been charged. A prosecution team, they don't exonerate people.”

Declination letters from a prosecutor, Cohen said, let the target know “we decline to prosecute you. They typically also have a caveat that this has no legal consequence, and that they reserve the right to reverse their stance if new evidence changes their assessment.”

A lawyer for Trump declined to comment Tuesday.

Prosecutors, of course, don't always bring criminal cases against targets of an investigation. There are any number of reasons for this. Witnesses might not fully cooperate. The evidence just might not be there. “What has been shown is no collusion. No collusion. There has been absolutely no collusion,” Trump told reporters this month.

Sometimes, a federal grand jury—perhaps not sold on the day's ham sandwich—decides not to indict. In that case, any would-be defendant could wave around a copy of the “no bill.”

The U.S. Justice Department publicly posts some of its declination memos concerning companies that were under investigation for possible foreign-bribery violations.

These memos are not highly detailed recitations of the facts—and, anyway, they do in some instances reveal criminal activity. The public availability of Foreign Corrupt Practices Act declination memos gives companies some thinking about effective compliance programs and how much goodwill cooperation might engender.

Mueller might have reasons for a detailed or less detailed memo, if he sends one at all—to anyone. But that memo almost certainly would not “exonerate” the target or otherwise declare innocence.

Even juries don't do that. You're either guilty or not guilty. They don't say you are innocent.

Read more:

Debevoise Partner Leads Deutsche Bank's Response to Mueller's Russia Probe

The $6.7M Tab for Mueller's Russia Investigation Will Grow

Akin Gump Lawyer Was Compelled to Testify at Manafort Grand Jury

Mueller Bolsters Russia Teams Appellate Readiness in New Hire

Trump's AG Pick Once Told Yates to 'Say No' to Improper Demands

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

4th Circuit Upholds Virginia Law Restricting Online Court Records Access

3 minute read

'Where Were the Lawyers?' Judge Blocks Trump's Birthright Citizenship Order

3 minute read

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Government Attorneys Face Reassignment, Rescinded Job Offers in First Days of Trump Administration

- 2Disney Legal Chief Sees Pay Surge 36%

- 3Legaltech Rundown: Consilio Launches Legal Privilege Review Tool, Luminance Opens North American Offices, and More

- 4Buchalter Hires Longtime Sheppard Mullin Real Estate Partner as Practice Chair

- 5A.I. Depositions: Court Reporters Are Watching Texas Case

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250