Disabled Lawyer Seeks to 'Create Change' With Courthouse Access Litigation

Caner Demirayak has sued both New York City and New York State under the Americans with Disabilities Act and other laws. He is trying to compel the Kings County Supreme Court civil courthouse to remove structural barriers that he says impinge on his lawyering.

January 02, 2018 at 06:23 PM

23 minute read

Caner Demirayak

Caner Demirayak

The courtroom in Brooklyn overflowed with lawyers waiting on the calendar call. Caner Demirayak, sweating slightly, sat in his 24-inch-wide Invacare Nutron wheelchair and maneuvered himself up through the crowd. The young lawyer had motion papers stuffed under his arm.

He was there to argue liability in a car accident case. But first he had to hand up the reply motion papers to a judge's clerk. It soon became clear that his motorized wheelchair, one of the most compact available on the market, would not squeeze between the courtroom rail and a bench.

Anxiety rippled through him. A 28-year-old trial lawyer with Becker's muscular dystrophy, a disease that causes his muscles to waste away, Demirayak had run into a maze of barriers inside the cramped courthouse before.

“Go against the wall,” a clerk yelled at him, he alleges in court filings. Minutes later the judge announced that his motion was adjourned because she had not received the papers.

“I don't care, in my [courtroom] I must read all the documents,” the judge told him as he tried to explain the reason for his delay, according to Demirayak.

Demirayak's next move was to ride to the back of the room and Google up on his iPhone the Department of Justice's regulations under the Americans with Disabilities Act. On that morning in October 2016, he began to consider bringing a lawsuit.

In September 2017, he launched his case, after what he describes as a series of increasingly frustrating and sometimes career-impairing incidents over the past year.

“It was really upsetting. It shook me up some,” Demirayak said of the calendar-call incident. “I'm trying to figure out [by looking up the regulations] if they're right” to adjourn my case, he said. “Maybe I should have gone up there [to the clerk] earlier, or something.”

He also remembers feeling humiliated as 40 or 50 fellow attorneys watched him lose the chance to argue his motion.

Demirayak has sued both New York City and New York State, under the ADA, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Constitution's equal protection clause, the state's Human Rights Law and the city's markedly progressive Human Rights Law. He is asking for significant structural changes to the Kings County Supreme Court civil courthouse, at 360 Adams St. in Brooklyn, where he appears as a lawyer, often several times a week. He is also asking for money, making an initial demand of at least $1 million in compensatory damages.

Court administration, meanwhile, has said that city court facilities are being surveyed to assess their needs and that physical changes to at least some buildings will follow. The state has also taken steps to have the lawsuit dismissed.

Demirayak, 29 and about three-and-a-half years out of law school, handles personal injury cases for James G. Bilello & Associates, a 50-lawyer firm in Hicksville. The cases usually come from car accidents.

In his federal ADA lawsuit, which may present certain issues of first impression for the court, he is proceeding pro se, representing himself.

“I know that the suit helps me, but it also helps other disabled people, because I want to help everybody else try to move it [the issue of better courthouse access] along,” Demirayak said recently of his goals for the legal action. “This is exactly the purpose of law and justice. You can't change people's social or psychological views of the disabled, but you can pass laws and push in the courts and compel judges to create case law, and that can allow disabled people to be out there more in society. And the more disabled people there are in the world out in public life, the more people accept them. And you create change.”

Lodged by a Lawyer, Not a Litigant or Juror

What may set Demirayak's suit apart from courthouse access suits filed over the years, in both New York and other states, is the myriad ways in which he uses 360 Adams St. as a practicing lawyer.

Many ADA-based lawsuits that focus on courthouse access have featured, as plaintiffs, people brought into courtrooms temporarily, such as disabled criminal defendants, civil litigants or jurors. They're often there for particular cases held in one designated area. States and other localities operating the courthouses have often argued that temporary fixes, such as moving a trial from one courtroom to a more accessible courtroom, were appropriate accommodations. In other words, they've maintained that a one-off fix, or limited fixes, were enough.

In Demirayak's lawsuit, he describes numerous incidents, spanning more than a year, that he alleges have happened in various parts of the massive, 10-story Adams Street courthouse. He argues sweepingly, in a 20-page amended complaint, that he is suffering harm of a “continuing nature” as “each and every time plaintiff [Demirayak] performs attorney work in the courthouse, he is injured again and again.”

One key to Demirayak's suit may be whether a judge or jury decides that some of the individual accommodations made for him, such as court administrators or judges switching a hearing, trial or conference to an area of the courthouse he could better negotiate, reached far enough in protecting him such that the accommodations blunted his claims that his career and livelihood are continuously being damaged and that he does not have equal courthouse access.

“They [New York City and state] may try to say they've provided him with reasonable accommodations when he has requested them and when they've been necessary,” said Michelle Caiola, the director of litigation for Disability Rights Advocates, a national civil rights group, who reviewed Demirayak's complaint. “It will be a matter of showing that is not going far enough to create equal access.”

“This isn't a one-off situation for him,” she added, “where the court system can accommodate him on a one-off basis. For him to have full and equal access to the courts, they're going to have to remove a lot of barriers.”

Caiola also said, “The goal of the ADA is to bring people with disabilities fully into all aspects of life—employment, a social life, etc. It's supposed to protect them from some of these very humiliating experiences he [Demirayak] is describing.”

Demirayak claims he's faced impingement almost everywhere in his near-daily experiences inside the Adams Street building.

“There's no courtroom that is completely ADA accessible,” according to Demirayak, who says he has handled hearings and trials in about 20 of the facility's dozens of courtrooms. “And when you're in one of the courtrooms, it's too narrow, too difficult to navigate it. You're making awkward and embarrassing positions in your wheelchair, trying to turn it around and fit yourself in the well of the courtroom, to address the jury.”

“And when you're doing sidebars with the judge,” he said, “the bench is too high, so you're looking at the wall from your wheelchair. So you have to ask the judge to come down off the bench, so you can be heard and can do the sidebar. It shouldn't be that way.”

Also, “one of the main problems is, you're assigned to a particular judge on a particular floor, and then at the recess, you can't use the bathroom on your floor.

“Sometimes you have to go to five different floors—you're just searching for a bathroom you can use with a working toilet you can fit into,” he said. And back in the courtroom “everyone's waiting for you, and then you're not on time.”

In his complaint, Demirayak also alleges that in January 2017, he was hindered as he tried a case on the courthouse's third floor, because the “courtroom was especially difficult to maneuver in.”

“Each time the plaintiff wanted to move around in the courtroom, every person had to stand up and move out of the way,” he wrote. “Further, the lawyer tables had insufficient space for wheelchairs. The plaintiff often tried to move around during the trial, but there was no room to do so.… The plaintiff wanted to speak with his independent eyewitness and client, but could not, due to the insufficient space in the courtroom.… When the plaintiff called these two individuals as witnesses, he was actually unsure if they were in the courtroom or outside waiting.”

He also alleged that in July 2017, he tried, unsuccessfully, to use the courthouse's third-floor law library for the first time.

“When the plaintiff entered the doorway near the law library he noticed the library went down to a lower floor with a set of stairs,” he wrote. “An unknown person standing nearby then shouted, 'Damn that sucks!'” according to the complaint.

Caiola said the fact that Demirayak is a lawyer helps differentiate his court access case from others. It's a case to watch, she said.

“I think his suit makes sense,” said Caiola, “and a judge should be able to understand it.”

“Many courthouses have tried to address this issue [access for the disabled] and some have done better than others,” she noted. “For instance, in Minnesota they have made all sorts of changes. There is a judge there with a disability. California has done better than New York.”

But “a lot of the courts are old buildings, and they all have not been remediated to remove the barriers,” she said.

Citing his own research, Demirayak said he failed to turn up a court access suit brought by a disabled lawyer, although he acknowledged his research was not exhaustive.

“I don't know any wheelchair-bound lawyers. It's so rare,” he said. “Probably because they are deterred, because the system is so bad. I mean, how are you going to be a lawyer if you can't do your job?”

The City's and State's Defenses

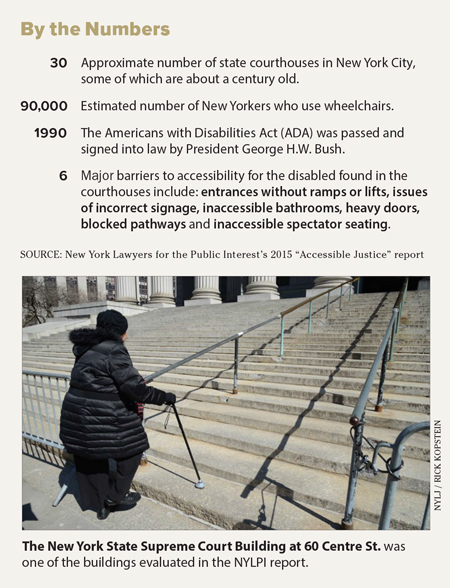

There are more than 30 courthouse facilities across New York City's five boroughs, including multiple buildings that are nearly a century old. They encompass millions of square feet. The buildings are owned and maintained by the city's Department of Citywide Administrative Services. But the legal services provided within the facilities are under the aegis of the state's Office of Court Administration.

Demirayak names as defendants in his lawsuit the city, the state, DCAS, OCA, the city Department of Buildings, and various officers from the agencies.

The defendants' responses thus far, in statements to the Law Journal and in papers filed with presiding U.S. District Judge William Kuntz II of the the Eastern District of New York, have been mostly terse. Still, the lawsuit is in its early stages. No motion to dismiss has yet been filed, and Demirayak has agreed with defense lawyers that he'll file a slightly amended complaint later this month.

“There is not much I can say as this is pending litigation,” said Lucian Chalfen, an OCA spokesman, in a recent email to the Law Journal. “Facilities issues should be directed to New York City, as they are required by statute to provide and maintain the courthouses. However, we are working with the city in an assessment of needs in all our buildings at which point they will be implementing physical changes.”

In a follow-up email, Chalfen noted that 20 courthouse surveys assessing the buildings' accessibility and potential needs had been completed by Jan. 1, 2018, including a survey of the 360 Adams St. building.

“OCA continues to fully cooperate with the city by arranging for total access to the courthouses, including night and weekend access,” Chalfen added by email.

“It's being addressed, and we're participating with the city,” he also said by phone, adding that the city “should get into telling you what they're doing [in assessing buildings' needs].”

Meanwhile, the city, in its Dec. 6, 2017, answer to Demirayak's complaint, was to the point. Signed by Agnetha Jacob, a Law Department attorney, the answer denied nearly all allegations and said little else.

Apart from that document, the city has not provided a response. Lisette Camilo, DCAS's commissioner, did not respond to an email seeking comment for this story. The media office for Mayor Bill de Blasio also did not respond to a request for comment. The city Law Department, which is representing the city, its agencies and named city officers, declined to comment.

The state, in a Dec. 1, 2017, letter to Kuntz submitted by Carly Weinreb, an assistant state attorney general, took a more detailed and expansive position. The state asked Kuntz to grant it a premotion conference in anticipation of the state and OCA executive director Ronald Younkins filing a motion to dismiss, and in the letter, Weinreb laid out several anticipated bases for the motion. She wrote, for instance, that Demirayak's complaint “is devoid of allegations directed specifically at the state of New York, Younkins, or OCA” and that its “threadbare recitals of a cause of action's elements, supported by mere conclusory statements, fail to state a plausible claim.”

Weinreb also argued that the U.S. Constitution's 11th Amendment immunity barred Demirayak from asserting state law claims against the various state defendants in federal court, and thus his Human Rights Law claims, as well as claims for intentional interference with contract, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and humiliation, should be dismissed.

In responding with a letter of his own to Kuntz, Demirayak argued that the state and OCA had received federal funds and waived immunity. He also wrote that, “when read liberally, the complaint clearly states a plausible claim under Title II of the ADA as well as Section 504 [of the Rehabilitation Act] and for equal protection.”

One thing seems certain: The battle over the facts and law, including the ADA, will be hard-fought. Generally, for facilities built before the ADA was passed in 1990—such as 360 Adams St., constructed in 1958—the building does not need to use “any and all means” to make its services accessible. It only needs to provide “meaningful access,” case law and experts say.

And, reasonable modifications do not require fundamentally altering the nature of the service provided or imposing an undue financial or administrative burden on a facility owner. But if modifications or temporary-type methods of fixing an access issue are not effective in achieving compliance with disability laws, the law may require architectural changes to be made.

Sarah Bell, special counsel at Pryor Cashman in Manhattan and co-chair of the firm's Americans with Disabilities Act defense practice, said in an interview that “based on my read [of Demirayak's lawsuit], there are some unique circumstances here.”

But she also said there may be “middle-ground accommodations that can be made.”

“If you think about a judge's bench being up two or three steps,” for example, she said, “there are less intrusive ways of overcoming those steps than renovating the courthouse.”

She noted that “the [ADA] law is about 27 years old, and a lot of the newer buildings [built in recent years] are more compliant.”

But “all around the country, courthouses are some of the oldest buildings we have, and when they were built, handicapped access was not the primary concern.”

“For a government facility,” she said, “I have a feeling the most major defense is going to be feasibility, and No. 2, financial concerns. I can't imagine that state governments are going to be able to afford to go and renovate all their courthouses.”

The Condition of City Courthouses

Demirayak is hardly alone in drawing focus to difficulties faced by disabled people, whether everyday working lawyers or one-time visitors, who try to access New York City's courts.

In March 2015, for instance, the New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, a nonprofit civil rights organization, issued a 20-page report that found that “New Yorkers with physical disabilities face an array of accessibility barriers in all areas of courthouses throughout New York City, denying them meaningful access to justice in a most fundamental way, in violation of federal, state and local laws.”

The report, based on a review of 10 of the more than 30 courthouses and holding pens for criminal defendants across the five boroughs, was said to be a first-of-its-kind widespread look at courthouse accessibility in the city.

Barriers to accessibility for the disabled were found to be rife, including “entrances without ramps or lifts, issues of incorrect signage, inaccessible bathrooms, heavy doors, blocked pathways and inaccessible spectator seating,” according to Maureen Belluscio, a Disability Justice program staff attorney with NYLPI, who testified in June 2016 before a New York City Council committee.

The 2015 report itself stated that “the difference between an accessible courthouse and an inaccessible courthouse can mean, for example, the difference between whether or not a person who uses a wheelchair is able to participate in jury duty, represent a client during a court proceeding, or have a job in the courthouse.”

It also said that “while barriers found in the design and layout of courtrooms, holding pens and booking areas may require architectural modifications to be eliminated, justice demands that New York City and State governments devote resources to ensuring that people with disabilities have equal access to the city's system of justice.”

Yet, at the same time, it noted that “based on our sample of courthouse assessments, the fixes for at least some of the problems identified in this report do not necessarily involve costly architectural changes. Rather, with proper signage and adequate training, many barriers can be remedied at little cost.”

In the wake of the report, the city and New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, and four of the group's clients, entered into what the NYLPI has described as a “groundbreaking” structured negotiations agreement.

“To the knowledge of all parties, this is the first time that the city of New York has entered into a structured negotiations agreement of this kind,” Belluscio noted in her 2016 testimony.

“The city, NYLPI and our clients will address a number of topics, including improving the physical accessibility of existing courthouse facilities as well as any new construction, improving training for city employees assigned to work at courthouse facilities, and the city's data collection processes,” said a July 2016 posting on the NYLPI website.

Suzanne Lynn, general counsel at DCAS, said in city council testimony in June 2016, “Under the agreement, both the city and NYLPI will negotiate, in good faith, on issues related to physical accessibility of courthouses in the city. As an incentive to engage in these discussions, both sides preserve their claims and defenses while the negotiations are ongoing.”

The structured negotiations continue today.

Lynn also pointed out several steps DCAS had already taken in recent years to improve access to city courthouses. They included working to retain an architectural firm to provide services aimed at “bringing DCAS-managed court buildings into compliance” with disability laws, as well as adding 162 new ADA signs to the outside of courthouse buildings as of 2015.

Meanwhile, in September 2017, New York state's chief judge and its chief administrative judge announced the formation of a 17-member advisory panel that will propose ideas for improving disabled people's ability to access and navigate the state courts, including those in New York City.

Demirayak's Fight

In January 2017, months after the incident that help spur Demirayak to file his suit, he was back in the courtroom, trying another case at 360 Adams St.

Negotiating the courtroom's well slowly and awkwardly in his wheelchair, he was once again confined to the room's small center, along with cramped areas around the lawyers' tables. He was on the fourth floor of the building, and his adversary, counsel for a plaintiff in a car accident case, was suddenly referring to Demirayak's disability as he made an opening argument to the jury.

“Will you be able to put away the fact that this attorney [for the defendant] is in a wheelchair, and focus on my client?” the plaintiff's lawyer said, according to Demirayak.

Moments later, Demirayak rode up through the courtroom's well, approaching the jury box in his wheelchair so that he could make an opening argument of his own. As he tried to inch close to the jury, though, he didn't see a podium that had been set up behind him. His wheelchair slammed into it, toppling the podium. It hit the ground with a thud.

Some jurors instantly reacted by putting their faces in their hands, Demirayak recalls today. His own face flushed red in embarrassment.

“I was definitely seething,” Demirayak said, “because any little thing can ruin a case in front of a jury.”

He soldiered on, though, while quickly deciding to reference his own disability now that his adversary had brought it up.

“Man, this courtroom could be in much better form, huh,” Demirayak recalled telling the eight jurors. Then, transitioning from his own predicament to his client's defense, he said, “It looks like my client is not the only one being treated unfairly.”

For 11 years, Demirayak has been confined to his black, sleek wheelchair. It has become a part of him—part of his life throughout college at Hofstra University, through law school at St. John's University, and now as a busy lawyer.

As the muscular dystrophy with which he was born is known to do, it has grown worse, tearing down his muscles increasingly each year. He now has lost nearly 90 percent of the muscles in his upper legs, he says.

But he appears hearty, and is deeply involved in his caseload. A slightly stout, round-faced man who favors square-shaped glasses, Demirayak is nearly a fixture inside the Adams Street building these days. On a recent afternoon, he stopped to talk frequently in the hallways with fellow lawyers, joking with them as he stared up from his chair. Then he kibitzed with courthouse staff and shared a laugh with them. He's social, and often engaging.

Workers in the building recognize the uphill battles he faces in negotiating the courtrooms, bathrooms and areas found up stairways. But Demirayak said they also seem unsure of what to do about it.

“Even court officers have said something to me about the problems,” he said. “And a few judges who I've appeared before have asked me, 'When are you going to do something about this?'”

“One judge, I got a defense verdict before him, and he said afterwards, 'You know, you're really good at this stuff [litigation]. You got to sue, you got to try to make a change in the courthouse. Maybe you can do it.” Demirayak declined to name the judge.

But at the same time, Demirayak has already hit roadblocks in his lawsuit, though the case is still in the early stages.

In October, for instance, Demirayak moved for a preliminary injunction before Kuntz. He asked for fast remedies such as correct signs for the disabled in the courthouse, temporary portable ramps and lifts in certain places, and for a government-submitted plan outlining the ultimate removal of architectural barriers.

Otherwise, he argued, he'd suffer “imminent irreparable harm.”

Kuntz denied the injunction motion swiftly, then issued a written ruling.

“Plaintiff seeks far more than merely prohibitory relief or to maintain the status quo,” the judge wrote. “Although the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act do provide for such permanent, prospective relief, it is typically available only as a remedy after a finding of liability. If the court granted plaintiff's request at this juncture, it would be giving him the ultimate, final relief he seeks without requiring him to prove the merits of his case at trial.”

Demirayak, in turn, appealed the preliminary injunction denial to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. He also asked the circuit for emergency relief pending the appeal. The circuit heard arguments on the emergency motion in early December and denied it on Dec. 7, though the appeal itself is still pending.

Now, Demirayak is back to focusing on the main case, which appears likely to unspool over many months or years. He said he is undaunted by the injunction setback, and he still spends at least several hours a week on his pro se pursuit, while also carrying a full-time law practice.

He works on letters to Kuntz and on court filings late into the night in his one-story Long Island home, he said. He's now also planning to file a separate lawsuit by the middle of 2018, which will focus on the “other New York City courthouses I'm aware of” that he says are likewise plagued by barriers for the disabled.

“I sent a letter to a government lawyer this week,” he said in late December, “asking them what they're doing to fix other court buildings—Queens, the Bronx, Manhattan, Staten Island.”

“I'm not going to be always working in this particular courthouse in Brooklyn, and the fact that they're not accessible deters a lawyer from wanting to work in other places,” he explained, while noting that his second suit may end up consolidated with the first. “My whole argument is that I may have taken a job that would involve those courthouses, but it [the barriers] deters you from taking those cases.”

As for the effort and motivation involved in pushing forward his lawsuit and the fight that lies ahead, Demirayak said he is secure about what he is doing and why he's doing it.

“I have disabled friends who have been trying to get out of the system of long-term care for years,” he said, his voice growing quieter and steady. “But they can't, because the government only allows them to make a certain amount of money or they get their benefits cut. And you're talking about benefits where the person needs to be lifted out of their bed, have their lives put together.

“They're bright people and they want to contribute to society,” he continued. “And so you have the ADA law, but you don't have people in the government who strongly believe that they [the disabled] should be in the workforce. They're not removing the barriers. It's a by-product of their own belief.

“I'm a big believer in justice and the rule of law. I'm a civil rights person—I think everyone should be treated equally under the law. So this is my chance to compel the government, to push the government along, to make sure that the last group of people who were given their civil rights, the disabled, are more integrated into society.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Decision of the Day: Court Holds Accident with Post Driver Was 'Bizarre Occurrence,' Dismisses Action Brought Under Labor Law §240

Cleary vs. White & Case: NY Showdown Over $5 Billion Brazilian Bankruptcy

Trending Stories

- 1How Gibson Dunn Lawyers Helped Assemble the LA FireAid Benefit Concert in 'Extreme' Time Crunch

- 2Lawyer Wears Funny Ears When Criticizing: Still Sued for Defamation

- 3Medical Student's Error Takes Center Stage in High Court 'Agency' Dispute

- 4'A Shock to the System’: Some Government Attorneys Are Forced Out, While Others Weigh Job Options

- 5Lackawanna County Lawyer Fails to Shake Legal Mal Claims Over Sex With Client

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250