Trump's DOJ Is 'Misleading' Court in Emoluments Suit, New Study Claims

A comprehensive study of the historical meaning of "emolument" broadly attacks the U.S. Justice Department for using an "inaccurate, unrepresentative and misleading" definition in its opposition to a lawsuit that accuses President Donald Trump of violating anti-corruption provisions in the Constitution.

July 26, 2017 at 03:32 PM

6 minute read

A comprehensive study of the historical meaning of “emolument” broadly attacks the U.S. Justice Department for using an “inaccurate, unrepresentative and misleading” definition in its opposition to a lawsuit that accuses President Donald Trump of violating anti-corruption provisions in the Constitution.

The Justice Department defines “emolument” as “profit arising from office or employ,” and claims that this “original understanding” is grounded in “contemporaneous dictionary definitions.” The government argues in the lawsuit in New York that the Constitution's emoluments clauses do not prohibit any company in which Trump has a financial interest from doing business with any federal, state or foreign government or person.

The government's “fragile dictionary-based argument is symptomatic of a weak grasp of American constitutional history in general,” said John Mikhail, the study's author and associate dean for research and academic programs at Georgetown University Law Center. “The argument is remarkably flimsy, bearing many of the marks of 'law office history' that make historians and sophisticated originalists wince.”

Mikhail's study traces how “emolument” is defined in English language dictionaries published from 1604 to 1806, as well as in common law dictionaries published between 1523 and 1792. He compares those definitions with the Justice Department's historical definition as it was presented in the government's challenge to the complaint in Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington v. Trump. That lawsuit, pending in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, alleged Trump's business interests have run afoul of the constitutional check against foreign influence.

The Justice Department declined to comment beyond its filing in the lawsuit.

Mikhail's study found that the term is not so highly restricted but instead has been defined more broadly as “profit,” “gain,” “advantage” or “benefit.” That interpretation could benefit the plaintiffs in the case against Trump.

To document his findings, Mikhail included in his article more than 100 original images of English language and legal dictionaries from 1523 to 1806, as well as complete transcripts and easy-to-read tables of the definitions contained in them.

Mikhail said in an interview that his interest in the definition of emolument was triggered by the white paper on conflicts of interest that Trump's lawyers at Morgan, Lewis & Bockius published in January. A team from Morgan Lewis worked with Trump to craft an ethics plan as he was preparing to take the White House.

Three things about the white paper, Mikhail said, jumped out at him: its embrace of originalism; its technical-seeming “office-and-employment-related” definition of “emolument” and the void of any founding-era evidence.

Mikhail said he “set all of my other research aside and focused entirely on compiling a comprehensive set of dictionary definitions.” A research assistant, Genevieve Bentz, helped locate and organize many of the definitions, Mikhail said.

Some of his findings include, in Mikhail's own words:

â–º Every English dictionary definition of “emolument” from 1604 to 1806 relies on one or more of the elements of the broad definition DOJ has rejects in its brief: “profit,” “advantage,” “gain” or “benefit.” Furthermore, over 92 percent of these dictionaries define “emolument” exclusively in those terms, with no reference to “office” or “employment.” By contrast, DOJ's preferred definition—“profit arising from office or employ”—appears in less than 8 percent of these dictionaries. Moreover, even these outlier dictionaries always include “gain, or advantage” in their definitions, a fact obscured by DOJ's selective quotation of only one part of its favored definition from Barclay (1774).

â–º The suggestion that “emolument” was a legal term of art at the founding, with a sharply circumscribed “office-and-employment-specific” meaning, is also inconsistent with the historical record. A vast quantity of evidence already available in the public domain suggests that the founding generation used the word “emolument” in a broad variety of contexts, including private commercial transactions.

â–º [N]one of the most significant common law dictionaries published from 1523 to 1792 even includes “emolument” in its list of defined terms. In fact, this term is mainly used in these legal dictionaries to define other, less familiar words and concepts. These findings reinforce the conclusion that “emolument” was not a term of art at the founding with a highly restricted meaning.

“Perhaps most remarkably,” Mikhail wrote, “DOJ asserts that '[t]he history and purpose of the [emoluments clauses] is devoid of concern about private commercial business arrangements.' This assertion is false and inconsistent with the best explanation of the broad sweep of emoluments prohibitions adopted by American governments from 1776 to 1789, many of which were designed specifically to prevent corruption and restrain public officials from placing their private commercial interests over their public duties.”

Mikhail wrote in his conclusion: “DOJ's use of founding era dictionaries in its brief, however, leaves much to be desired. At best, its historical research was shoddy and slapdash. At worst, it may have misled the court by cherry-picking and selectively quoting its preferred definition, ignoring a vast amount of conflicting evidence.”

Mikhail said a second study is underway of dictionaries from 1806 to the present in an effort to see how and why definitions of “emolument” may have changed over time. If that study shows the definition has evolved more in line with the Justice Department's view, courts might be more likely to accept that view, he said.

Two points could push in the other direction, he said. “First, I assume that many judges might care more about the purpose of these clauses—to prevent corruption, conflicts of interest, and the like—and the extreme indifference and even contempt President Trump has shown toward well-established constitutional norms than they do about dictionary definitions or lexical meanings whether past or present,” Mikhail said. “Second, even DOJ's preferred definition of 'emolument' might prove difficult for the president.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

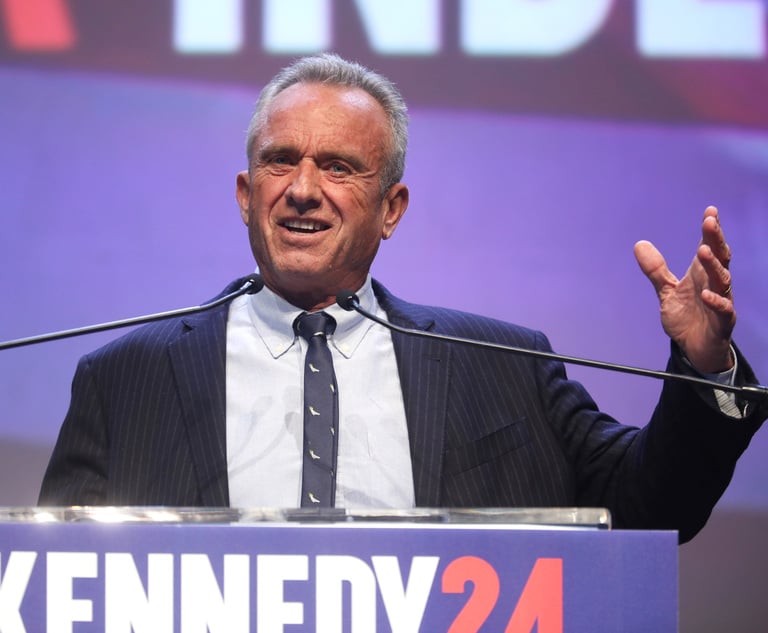

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute read

3rd Circuit Nominee Mangi Sees 'No Pathway to Confirmation,' Derides 'Organized Smear Campaign'

4 minute read

Judge Grants Special Counsel's Motion, Dismisses Criminal Case Against Trump Without Prejudice

Trending Stories

- 1New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 2No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 3Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 4Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 5Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250