Judge Tells EEOC to Revisit Rule for Workplace Wellness Programs

Regulation wasn't vacated outright for concern about "significant disruptive consequences."A federal judge on Tuesday sent the U.S. Equal Employment…

August 22, 2017 at 03:03 PM

4 minute read

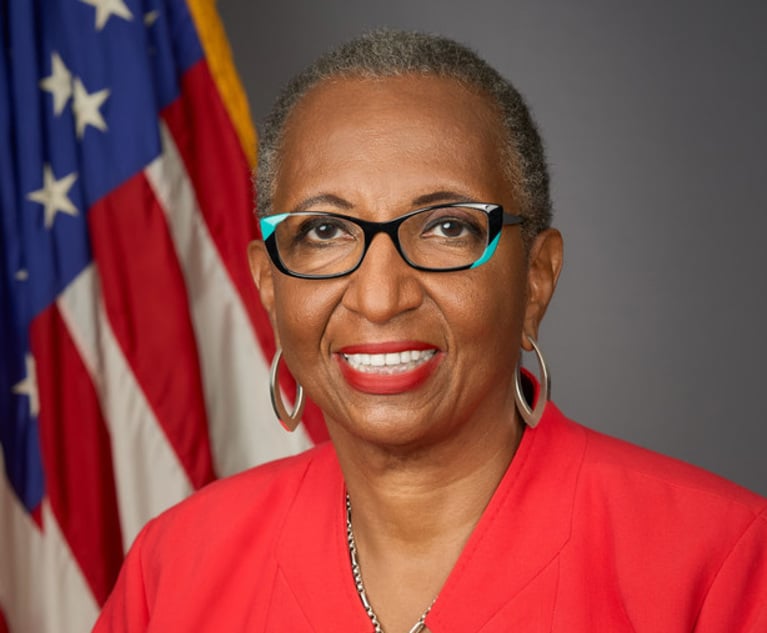

AARP headquarters in Washington, D.C.

AARP headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM

Regulation wasn't vacated outright for concern about “significant disruptive consequences.”

A federal judge on Tuesday sent the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission back to the drawing board on regulations for increasingly popular workplace wellness programs, ruling in part that the agency failed to justify its 30 percent cap on cost incentives for participating workers.

AARP challenged the rule in October, arguing it would allow employers to illegally access private health information and potentially use that data in a discriminatory manner. The AARP, which lobbies on behalf of nearly 38 million people age 50 and older, also alleged the 30 percent limit on health care cost incentives was too high of a penalty for nonparticipating workers.

In the rulemaking process, the EEOC determined a wellness program could be considered “voluntary” so long as the cost incentives—or, seen another way, the penalty for nonparticipating employees—did not exceed 30 percent of the value of an individual's plan.

In his decision, U.S. District Judge John Bates of the District of Columbia in Washington acknowledged the “tension that exists between the laudable goals behind such wellness programs”—which often entail collecting sensitive medical information from employees—and other federal regulations limiting employers' access to such data. But he found that the EEOC had failed to adequately explain its decision to interpret the term “voluntary” in those other regulations—the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act—to allow the 30 percent incentive threshold.

“Neither the final rules nor the administrative record contain any concrete data, studies or analysis that would support any particular incentive level as the threshold past which an incentive becomes involuntary in violation of the ADA and GINA,” Bates wrote. “To be clear, this would likely be a different case if the administrative record had contained support for and an explanation of the agency's decision, given the deference courts must give in this context. But 'deference' does not mean that courts act as a rubber stamp for agency policies.”

The EEOC and AARP—represented by its litigation arm, the AARP Foundation Litigation—did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Read more: Anthem, Cigna and Macy's Sued Over Wellness Plan

Bates' decision granted the AARP's motion for summary judgment against the EEOC rule. But Bates declined to vacate the rule entirely out of concern for “significant disruptive consequences.”

If the rule were vacated, Bates said, employees who've already received wellness program incentives “would presumably be obligated to pay these back,” while employers who effectively imposed a penalty on nonparticipating employees “would likewise be obligated to repay to employees the cost of the penalty.”

Protected health care information that was already disclosed to companies “cannot be made confidential again,” Bates said.

“It is far from clear that it would be possible to restore the status quo ante if the rules were vacated; rather, it may well end up punishing those firms—and employees—who acted in reliance on the rules,” Bates wrote.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

How Lower Courts Are Interpreting Justices' Decision in 'Muldrow v. City of St. Louis'

7 minute read

Troutman Pepper Says Ex-Associate Who Alleged Racial Discrimination Lost Job Because of Failure to Improve

6 minute read

Trump Fires EEOC Commissioners, Kneecapping Democrat-Controlled Civil Rights Agency

Trump’s Firing of NLRB Member Could Spark Review of Supreme Court Precedent

Trending Stories

- 1Jury Awards $3M in Shooting at Nightclub

- 2How Clean Is the Clean Slate Act?

- 3Florida Bar Sues Miami Attorney for Frivolous Lawsuits

- 4Donald Trump Serves Only De Facto and Not De Jure: A Status That Voids His Acts Usurping the Power of Congress or the Courts

- 5Georgia Hacker Pleads Guilty in SEC X Account Scam That Moved Markets

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250