Firms Say Suits Aimed at Trump's Policies Are Just Business as Usual. But Are They?

The professional class of Washington often repeats the refrain that the Trump administration is not normal. Since January, the lawyerati — especially at the dominant, large law firms in the nation's capital — have done plenty to signal their opposition.

September 29, 2017 at 11:55 AM

41 minute read

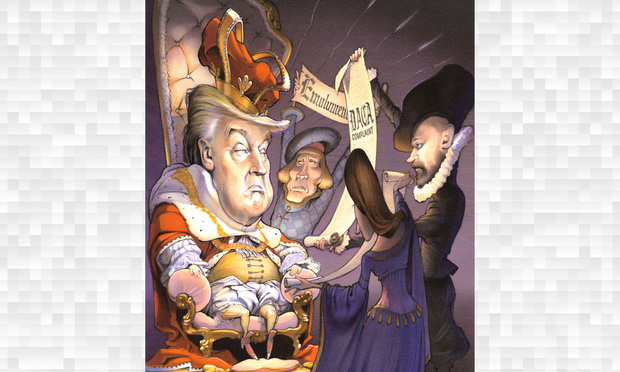

Credit: Bruce MacPherson

Credit: Bruce MacPherson The professional class of Washington often repeats the refrain that the Trump administration is not normal. Since January, the lawyerati — especially at the dominant, large law firms in the nation's capital — have done plenty to signal their opposition.

They've mobilized against immigration crackdowns. They've challenged President Donald Trump's transgender military ban. They've stood up for Twitter users blocked by Trump. They've questioned the president's business interests. They've publicly denounced the pardon of a sheriff who was in contempt of court. And, in guarded language, law firms decried the president's equivocation of white supremacists and anti-hate opposition.

The list seems likely to grow as long as Trump is in office. But is the legal industry really in uncharted territory? Despite the growing number of actions they've taken, even Trump's foes say not yet.

Jack Rakove, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and Stanford University professor, has confronted the question while probing Trump's presidential ethics. Rakove signed onto an amicus brief for legal historians in the federal case that challenges Trump companies' earnings and the conflicts of interest that may arise from them while he is a public officeholder.

If there's a difference in the legal establishment's response to Trump, it's a matter of intensity, Rakove suggests.

“In one sense, the Trump administration is so offensive on so many grounds. Its policy-making is so suspect, and its political impulses seem so vicious and small-minded,” Rakove says. “On the other hand, it seems to me there has been over the last decade or decade-and-a-half this ramping up of litigation.”

Status Quo — Or No?

Cases that push back against an administration's policies are, historically, as common to Washington as steak-and-brown-liquor client dinners. There were efforts during past presidencies to preserve the rights of detainees at Guantanamo Bay, for example, and legal challenges that paved the way for same-sex marriage.

Or take the recent efforts of two quintessential D.C. firms: Covington & Burling and Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr. Both are challenging attempts by the administration to cut federal funding for so-called sanctuary cities. They're also both challenging the president's ban on transgender people in the military.

But both firms have long taken up civil rights work — including LGBT and immigration rights causes — and not only when a Republican held the Oval Office. Paul Wolfson, the Wilmer partner handling the transgender ban case, says little has changed in his firm's approach. Wilmer is working on the case with Foley Hoag on behalf of two gay rights advocacy groups.

“It doesn't necessarily represent anything different from anything we would have done under any other administration,” Wolfson says. “It was obvious to us this was a situation where there was serious need and people would be suffering harm.”

Wolfson's colleague, Wilmer partner Jamie Gorelick, spearheaded briefs for immigrant rights groups in sanctuary city cases from San Francisco and Santa Clara, California. Gorelick previously represented presidential advisers Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner on their federal disclosures and says those client representations don't preclude her from working on federal policy challenges.

As the year progresses, firms are devoting more of their litigators' time — millions of dollars' worth — to cases that oppose Trump.

Covington's matters touch on nearly every major policy challenge against the president. That includes representing Los Angeles in a sanctuary city case and the University of California school system against the president's previously announced rollback of immigration protections for undocumented children. The firm also brought a class-action case against Joe Arpaio and filed a recent brief disagreeing with the Justice Department's stance toward the pardoned Arizona sheriff.

Even weeks before Trump took office, Covington partner Eric Holder Jr., Obama's first attorney general, inked a $25,000-a-month contract with the California Legislature to examine ways the state could oppose Trump, an arrangement that ended after four months.

Conversely, Covington represents former Trump National Security Adviser Michael Flynn, who is under investigation, and the firm had challenged the previous administration on behalf of detained undocumented immigrants fleeing violence in Central America. Another Covington partner worked during the Obama years to roll back historical policies that excluded transgender people from the military.

Mitch Kamins

Mitch Kamins“It's obviously a different posture when you're advocating to change an existing policy,” says Mitch Kamin of Covington. The new transgender ban challenge stands out, he says, because “litigation wasn't needed the last time around, and it's really the tool that's required here.”

Jenner & Block, another corporate defense firm with a substantial D.C. presence, is challenging Trump's use of Twitter after he blocked users from following and messaging his account. The case tests First Amendment principles — familiar territory for Jenner.

“This is just an application of work we had done before, with a new set of facts,” Amunson says.

Ramping Up

Though they're largely a socially progressive bunch, corporate lawyers are just as capable of clustering behind conservative politics. The Clean Power Plan, for instance, during the Obama years prompted a parade of large law firms to join the opposition.

Even so, Trump-era legal challenges can feel like a lopsided seesaw. Large firms with surprising swiftness are signing on to cases and briefs that challenge the president.

For instance, firm pro bono departments sprung into action following Trump's first executive order on travel hours after the president signed it. The order banned citizens from seven Muslim nations from entering the U.S. Thousands of lawyers rushed to airports around the country to help detained travelers, and law firms like Mayer Brown and Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton peppered courts with emergency petitions that January weekend.

Former acting U.S. solicitor general Neal Katyal, a partner at the global firm Hogan Lovells, filed a challenge on behalf of his client, the state of Hawaii, days after the president announced the ban, and stuck with it after Trump revised his order.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Lavish 'Lies' Led to Investors Being Fleeced in Nine-Figure International Crypto Scam

3 minute read

Meta Hires Litigation Strategy Chief, Tapping King & Spalding Partner Who Was Senior DOJ Official in First Trump Term

‘Issue of First Impression’: New York Judge Clears Coinbase Appeal Amid Crypto Regulatory Clash

4 minute read

‘Not a Regulatory Gray Area’: CFTC Secures $5M Settlement From Gemini

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250