U.S. Labor Department headquarters in Washington, DC. Credit: Mike Scarcella/ ALM

U.S. Labor Department headquarters in Washington, DC. Credit: Mike Scarcella/ ALMWhat the US Labor Department's Overtime Appeal Means for Companies

The fate of the Obama-era regulation that made millions of more workers eligible for overtime pay remains unresolved after the U.S. Labor Department on Monday moved to defend the agency's power to set such a rule. “There is a great deal of uncertainty and anxiety and ambiguity,” one lawyer said. “This might be the biggest mess I've ever seen. There are a lot of complicated issues."

October 30, 2017 at 06:41 PM

7 minute read

The fate of the Obama-era regulation that made millions of more workers eligible for overtime pay remains unresolved after the U.S. Labor Department on Monday moved to defend the agency's power to set such a rule.

The Labor Department, now under the leadership of Secretary Alexander Acosta, filed a notice of appeal challenging a Texas federal judge's ruling that stopped enforcement of the overtime rule. The agency, taking the case to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, will defend its authority to create and enforce such a regulation, otherwise leaving any potential new rule-making open to a challenge. Labor regulators faced a Tuesday deadline to appeal.

At issue is the 2016 rule that updated the federal salary threshold for overtime eligibility for the first time in 12 years, from $23,660 to $47,476. It made roughly 4.2 million workers newly eligible for time and half pay for work over 40 hours a week. Trump's Labor Department earlier said it would revisit the rule, with no certainty of using the Obama-proposed salary levels.

Business groups have been carefully watching this case and have hoped that the rule would be rescinded or altered under the Trump administration. The issue is more nuanced for regulators.

“As a lawyer, it made logical sense to appeal this decision,” said Patricia Smith, senior counsel at the National Employment Law Project

Smith, the former Labor Department solicitor in the Obama administration, said the Texas judge's decision would have made it difficult for any salary test to be issued and would open any rule to a new lawsuit.

“How is the Labor Department with any certainty going to promulgate any rule that would survive the challenge?” Smith said. “No matter what administration, the judgment circumscribed the department's historical ability to set and define the exception of a combination of salaries and duties.”

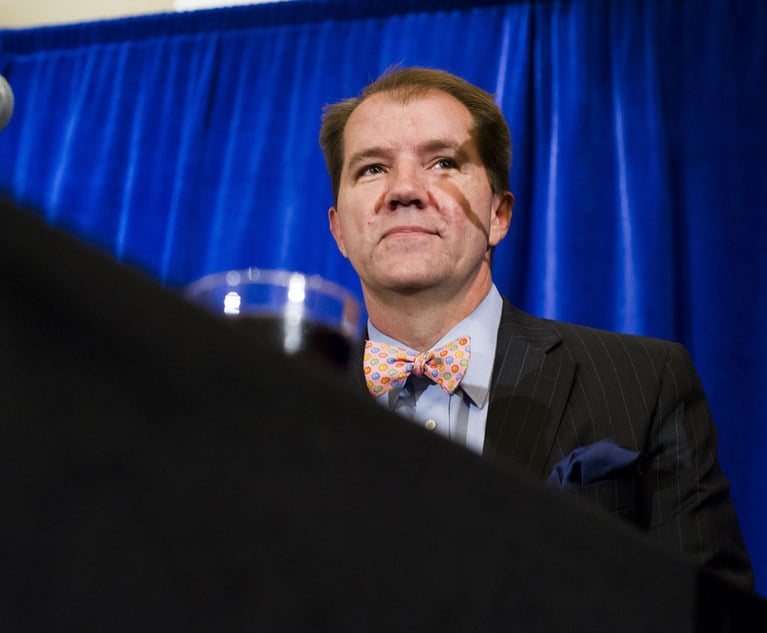

Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALMAcosta has said doubling the salary standard went too far. But he's supported raising the level, supporting a $33,000 threshold. The Labor Department this summer launched a new rulemaking process, gathering comments to enforce a new regulation. The thousands of comments exposed the complexities for companies in setting classifications to decide which workers should be eligible for overtime pay. Law firms and other experts weighed in on the various ways the issue should be addressed.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and several states sued over the rule last year.

A Chamber spokesperson said in a statement Monday: “We continue to believe the last administration went too far in its 2016 overtime rule, and have urged the department to issue a responsible update to the salary level. As necessary, we will defend the district court's opinion, which correctly struck down a rule that would have been disruptive to employers across the spectrum.”

Companies took different approaches before complying with the original rule before last year's deadline, which was set to take effect Dec. 1, 2016. Many changed the status of their employees, while others raised salaries. Some businesses hedged bets in the hope that the rule would be scuttled. Those that made changes would have a hard time reversing course, although Chipotle was challenged for allegedly taking such measures.

The language in U.S. District Judge Amos Mazzant of the Eastern District of Texas' decision to halt the overtime rule raised questions about the legality of regulators setting a salary standard. Currently, to classify an employee as exempt, or not eligible for overtime, or non-exempt, there is a duties test and a salary test.

|Companies Face Uncertainty in 'Biggest Mess'

The breadth of the language in the trial court ruling suggested the salary test may not be legitimate, said John Thompson, a Fisher & Phillips partner in Atlanta. He said it wasn't a surprise that the Labor Department decided to appeal.

For companies, the procedural wrangling will mean more uncertainty, he said.

“There is a great deal of uncertainty and anxiety and ambiguity,” Thompson said. “This might be the biggest mess I've ever seen. There are a lot of complicated issues. It goes on and on and on. It will not die.”

Fisher & Phillips filed one of the tens of thousands of comments to the Labor Department. The firm argued for eliminating the salary test entirely and only using a duties test to enforce the rule.

“What is the right number? Whatever you pick, whatever it is, it will carve out people who meet the exemption test,” Thompson said. He added, “Employers have to realize that the uncertainty continues. It's still too soon to know. It's not a satisfactory things for employers. The situation will remain uncertain and they will have to contend with that.”

Firms on both the management and plaintiff sides weighed in, arguing for how to classify workers. Littler Mendelson, like many other management-side firms, suggested that the rule be guided by standards that set the level in 2004, the last time the rule was updated before 2016. That rule simplified the duties and salary standards, something proponents of the Obama-era rule argued the higher salary threshold corrected.

In its analysis, Littler showed a survey that found about half of the nearly 900 responding employers implemented changes to comply with the 2016 final rule before the preliminary injunction was issued. Of the remaining respondents, 39.4 percent had made plans to comply, but did not implement anything new; and 10.6 percent had taken no steps to comply.

Workers rights group responded to the department's action and stressed that the higher salary set in 2016 needed to be upheld. The Economic Policy Institute issued a statement that said, in part, “The overtime rule update was a crucial, long overdue move to raise wages for middle-class workers. DOL should vigorously defend the 2016 threshold and not attempt to undermine it through the regulatory process.”

From the workers' perspective, the prior salary threshold—set in 2004—was not realistic, said Seth Lesser of Klafter Olsen & Lesser.

“If companies can get away with not paying overtime, they are very happy not paying it,” Lesser said. “I would suspect a lot of companies and management-side firms are having a hard time figure out what to do.”

Smith of the National Employment Law Project said the stakes are high for this question. She pointed to cases such as supervisors in the retail industry, who work long hours but may not be eligible for overtime, so do not meet minimum wage. She said if the salary level is lowered much less than the $47,000 level, a stricter duties test needs to be applied.

“Both Republican and Democratic administrations want to boost the middle class,” Smith said. “Should these workers get paid for working longer? Will that keep them in the middle class or prevent them from falling out?”

Read more:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'New Circumstances': Winston & Strawn Seek Expedited Relief in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute read

5th Circuit Rules Open-Source Code Is Not Property in Tornado Cash Appeal

5 minute read

DOJ Asks 5th Circuit to Publish Opinion Upholding Gun Ban for Felon

Trending Stories

- 1'We Will Sue ... Immediately': AG Bonta Says He's Ready to Spend $25M Battling Trump

- 211 Red State AGs Demand Damages in Antitrust Lawsuit Shaming ESG Climate Investors

- 3In-House Moves of Month: Discover Fills Awkward CLO Opening, Allegion GC Lasts Just 3 Months

- 4Delaware Court Holds Stance on Musk's $55.8B Pay Rescission, Awards Shareholder Counsel $345M

- 5'Go 12 Rounds' or Settle: Rear-End Collision Leads to $2.25M Presuit Settlement

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250