'Sleepless Nights' for D.C. Lobbyists Follow Manafort Indictment

The 12-count indictment against Paul Manafort and a business partner this week rattled Washington's K Street lobbying corps, as lawyers and consultants now find themselves forced to reassess their past disclosures and future compliance with rules that govern advocacy for foreign clients.

November 01, 2017 at 07:49 PM

7 minute read

The 12-count indictment against Paul Manafort and a business partner this week rattled Washington's K Street lobbying corps, as lawyers and consultants now find themselves forced to reassess their past disclosures and future compliance with rules that govern advocacy for foreign clients.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller's team, investigating Russia's interference with the 2016 presidential election, charged Manafort with lobbying for the Ukrainian government without registering with the U.S. Justice Department as required under what had been an arcane federal law: the Foreign Agents Registration Act.

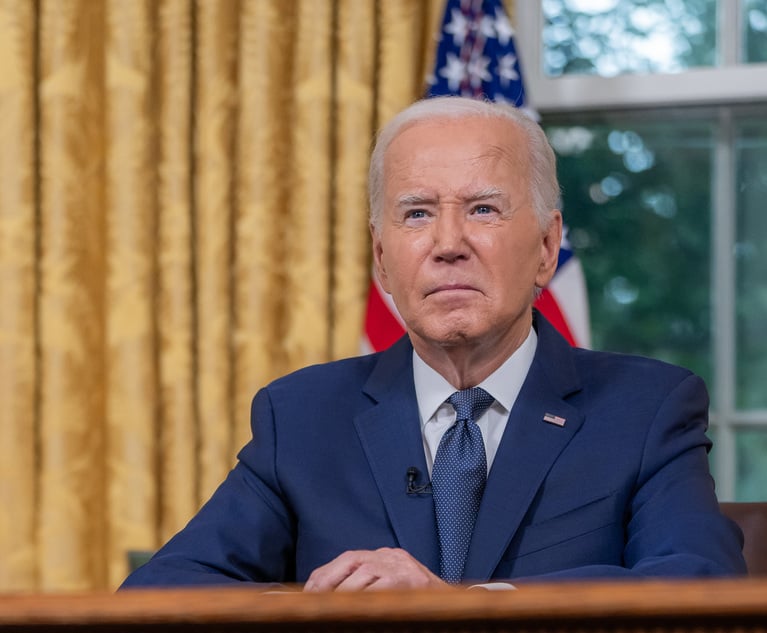

Paul Manafort

Paul ManafortManafort's indictment has thrust that law—passed in 1938 to combat a Nazi propaganda campaign in the United States—into the spotlight and spurred speculation that tighter enforcement and disclosure requirements will be coming to the influence industry.

“The phone has been ringing off the hook from organizations and companies who decided maybe they needed to reevaluate their obligations under FARA,” said Daniel Pickard, a Wiley Rein partner who specializes in international trade and election law. “I think there have probably been a lot of sleepless nights in D.C. this week.”

The questions primarily concern two areas: the scope of the activities covered under FARA and an exemption that allows lobbyists to instead report their activities under the federal Lobbying Disclosure Act, which demands less detailed disclosure.

Many lobbyists long have taken the view that unless they directly contact a government official on behalf of a foreign government, they are not engaging in activity that requires them to register with the Justice Department. Even behind-the-scenes activities such as public relations and political consulting in the United States require registration under FARA, according to lawyers who advise lobbyists and others on disclosure obligations.

“Without naming any names, I'll just say I have marveled at the fact that a lot of global consulting firms—and that's the only way I'm going to describe it—who get paid by foreign governments on policy matters to provide strategic advice almost pride themselves on not being FARA-registered,” said Mayer Brown senior advisor Toby Moffett, a FARA-registered lobbyist who sold his lobby shop, the Moffett Group, to the law firm in 2014.

“They sort of convince themselves that this is not lobbying for foreign clients,” he added.

Mueller's prosecution team accused Manafort and a business partner, Rick Gates, not only of failing to register as foreign agents but also of submitting “false and misleading” letters to the Justice Department in November 2016 and February 2017 after the government inquired about their lobbying efforts on behalf of the Ukrainian government and related foreign entities.

A former lawyer for Manafort who had sent the letters was ordered last month by a federal judge in Washington to testify before the grand jury Mueller's team convened in the Russia investigation. In a court ruling unsealed Monday, U.S. District Judge Beryl Howell did not identify the lawyer—a witness for the prosecution—but described her in a footnote as “an unwitting participant in the crime alleged.”

The National Law Journal confirmed this week that the lawyer was Melissa Laurenza, a partner at Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld who focuses on campaign law and lobbying registration matters. Laurenza has declined to talk about the Russia probe.

Kevin Downing, a lawyer for Manafort, this week called the government's charges “ridiculous.” He told reporters in a statement: “Today, you've seen an indictment brought by an office of special counsel that is using a very novel theory to prosecute Mr. Manafort regarding a FARA filing.”

|

New Focus on FARA Is 'Game-Changer'

Jason Abel, of counsel at Steptoe & Johnson LLP, said the Manafort indictment fueled already-building demand for understanding the contours of the Foreign Agents Registration Act.

Jason Abel of Steptoe & Johnson LLP

Jason Abel of Steptoe & Johnson LLP“I think this week's events are a game-changer with respect to attention paid on FARA. In my mind, there will be a renewed emphasis on exactly what is FARA, what activities does the law cover and what type of diligence do representatives need to do before engaging in those activities,” Abel said. “One popular misconception of FARA is that it only covers lobbying, and if you take one look at the law, you realize it's much broader.”

After peaking at 916 registrations in 1987, new entries under FARA dropped off in the mid-1990s. The Justice Department's national security division drew a connection to the 1995 passage of the Lobbying Disclosure Act, which “carved out a significant exemption” that allowed lobbyists to avoid registering under FARA if they represent a foreign commercial interest rather than a foreign government or foreign political party, according to a 2016 audit by Justice Department inspector general Michael Horowitz.

But the line between a commercial and state interest can be fuzzy. In some cases, lobbying is still funded or directed by a government or political party, with the commercial client serving as something of a front.

“I think due diligence should be conducted to make sure the entities represented are truly not foreign governments and foreign parties if you plan to take advantage of that exemption,” Abel said.

The law has been enforced with a light touch.

Between 1966 and 2015, the Justice Department “only brought seven criminal FARA cases,” according to Horowitz's report last year. Since 1991, the department's national security division has only once sought civil injunctive relief over an alleged FARA violation.

Congress has also taken notice. At a hearing in July, Sen. Chuck Grassley, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, said only 400 people are currently registered as foreign agents. “Does anyone seriously think that only 400 people in the whole United States take foreign money for P.R. and lobbying work?”

Before he sold his namesake lobbying firm to Mayer Brown, Moffett said he was “perennially horrified and losing sleep that maybe we weren't in compliance.”

“You look at these small firms like mine was, representing a country or two,” said Moffett, who previously served as a Democratic U.S. representative from Connecticut. “Those are the people tonight trying to find a law firm to tell them if they're OK.”

Read more:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

3rd Circuit Strikes Down NLRB’s Monetary Remedies for Fired Starbucks Workers

Longtime Baker & Hostetler Partner, Former White House Counsel David Rivkin Dies at 68

2 minute read

After 2024's Regulatory Tsunami, Financial Services Firms Hope Storm Clouds Break

Trending Stories

- 1'Largest Retail Data Breach in History'? Hot Topic and Affiliated Brands Sued for Alleged Failure to Prevent Data Breach Linked to Snowflake Software

- 2Former President of New York State Bar, and the New York Bar Foundation, Dies As He Entered 70th Year as Attorney

- 3Legal Advocates in Uproar Upon Release of Footage Showing CO's Beat Black Inmate Before His Death

- 4Longtime Baker & Hostetler Partner, Former White House Counsel David Rivkin Dies at 68

- 5Court System Seeks Public Comment on E-Filing for Annual Report

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250