Top Litigators Clash and Muhammad Ali Wins Another Round at Supreme Court

Theodore Wells Jr. of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison faced off against Donald Ayer of Jones Day Wednesday night in a reenactment of the boxing champ's 1971 Supreme Court fight for conscientious objector status.

November 09, 2017 at 12:16 PM

4 minute read

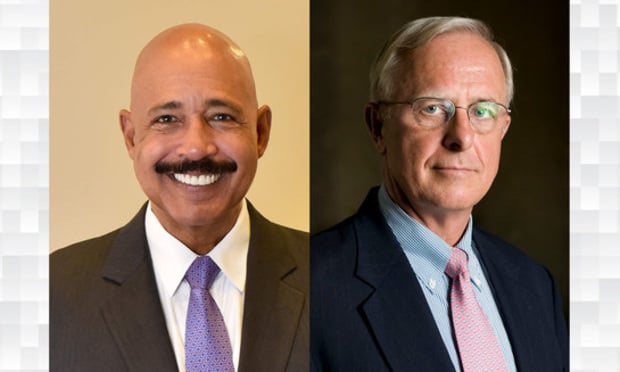

Theodore Wells Jr. of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison and Donald Ayer of Jones Day.

Theodore Wells Jr. of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison and Donald Ayer of Jones Day. Echoes of modern controversies could be heard Wednesday night in the U.S. Supreme Court chamber.

“The Muslim faith is not a pacifist faith,” one lawyer said. Another countered that Muslim doctrine does not require the faithful to “pick up a gun in any war.”

But the debate was not a rehearsal of litigation over the Trump administration's travel ban, or any other current headline-making case.

Instead, it was a “re-enactment” of the 1971 Supreme Court case Clay v. United States, in which legendary boxer Muhammad Ali appealed the rejection of his application for conscientious objector status at the height of the Vietnam War.

Sitting at the chief justice's center chair, Justice Sonia Sotomayor presided over the mock hearing sponsored by the Supreme Court Historical Society. Ali's widow Lonnie Ali and other family members attended too. Justice Clarence Thomas, who sometimes seems bored on the bench, watched raptly from a spectator's seat.

Sitting at the chief justice's center chair, Justice Sonia Sotomayor presided over the mock hearing sponsored by the Supreme Court Historical Society. Ali's widow Lonnie Ali and other family members attended too. Justice Clarence Thomas, who sometimes seems bored on the bench, watched raptly from a spectator's seat.

Veteran New York litigator Theodore Wells Jr. of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison argued on behalf of Ali, and when it was over, he tucked two quill pens—they are handed out to court advocates—into his breast pocket. The late civil rights lawyer Chauncey Eskridge argued for Ali in 1971.

Representing the government in opposition to Ali was Jones Day partner Donald Ayer, channeling long-ago Jones Day partner Erwin Griswold, who argued the Ali case in 1971 as U.S. solicitor general. A former deputy solicitor general himself, Ayer wore the traditional morning coat for the occasion.

Setting the stage for the event was former law school dean Thomas Krattenmaker, who clerked for Justice John Harlan II the year the Ali case was decided. Both Krattenmaker and Harlan played key roles in the “sub rosa” deliberation after the oral argument that turned a loss into a win for Ali, as Krattenmaker described it. Those behind-the-scenes maneuvers, recounted in a 2013 HBO movie, overshadowed the argument itself.

But Sotomayor made it lively nonetheless. Wells started out by requesting four minutes of rebuttal time, which high court practitioners don't ask for so explicitly. “Three,” Sotomayor shot back.

Considerable time was spent on the belligerence—or lack thereof—of the Muslim faith. A key issue in the Clay case was whether he and his religion eschew all wars, or just some wars—a factor used in granting or denying conscientious objector status. Ali's own statements about war were ambiguous.

Once the argument was over, Sotomayor amused the audience when she said, “Remind me if I ever have to sit in this chair again, I need to have it raised.” She recounted how the eight-member court—Thurgood Marshall was recused because of his involvement in the case as solicitor general—was ready to vote against Ali until Harlan, who was assigned to write the opinion, changed his mind. Krattenmaker had given Harlan a copy of Elijah Muhammad's “Message to the Blackman in America,” a book that convinced him that Muslims in general, and Ali in particular, were for all practical purposes opposed to all war.

Harlan's colleagues were not happy with his change of mind. “If anyone did that today, wow!” Sotomayor exclaimed. But Harlan's shift got other justices thinking about a compromise. In the end, the court issued a per curiam opinion that sidestepped controversial issues but ruled for Ali on grounds that the government was unclear about why he was denied objector status.

Describing Ali as “quite the poet,” Sotomayor tried her hand at poetry too in handing down the opinion Wednesday night. “We granted cert on a narrow question presented,” she said. “But now the government says, 'We never meant it.'” She finished by saying, “Mr. Ali, you're free. We reverse.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Law Firms Expand Scope of Immigration Expertise Amid Blitz of Trump Orders

6 minute read

Am Law 100 Lateral Partner Hiring Rose in 2024: Report

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250