Florida Houseboat Owner Lands Second Case at US Supreme Court

There is no question that financial trader and inventor Fane Lozman has been a thorn in the side of the city council of Riviera Beach, Florida, for more than a decade. And now—for the second time in five years—his legal battles with the city have captured the attention of the U.S. Supreme Court.

November 13, 2017 at 04:01 PM

7 minute read

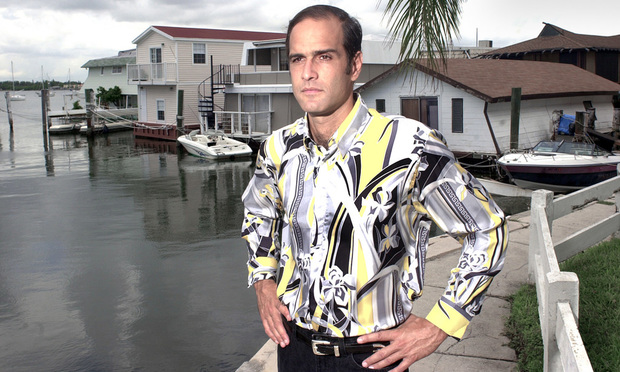

Fane Lozman in Florida. Credit: Melanie Bell.

Fane Lozman in Florida. Credit: Melanie Bell. There is no question that financial trader and inventor Fane Lozman has been a thorn in the side of the city council of Riviera Beach, Florida, for more than a decade. And now—for the second time in five years—his legal battles with the city have captured the attention of the U.S. Supreme Court.

The justices on Monday granted review in Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, a case that raises a very different legal question from the high court's first foray into this south Florida conflict in 2012.

“My legal team can't recall an individual petitioner going up [to the Supreme Court] and getting review of two totally separate circuit splits,” Lozman, a former U.S. Marine Corps officer, said Monday. “I'm thrilled. It's been a lonely fight for the last nine-and-a-half years.”

Lozman's two Supreme Court cases spring from his clash with the city over its use of eminent domain for redevelopment. Lozman has been an indefatigable critic of the city's efforts, and the city, according to his most recent petition, has tried to silence him in different ways.

“They've been angry ever since I killed their eminent domain deal,” he said. He noted he recently bought 25 acres of submerged land on Singer Island to develop into a community of floating homes. “They refused to give me an address and I had to fight that.”

Stanford Law's Pamela Karlan. Credit: Jason Doiy

Stanford Law's Pamela Karlan. Credit: Jason DoiyLozman, represented by Stanford Law School's Pamela Karlan, said he approached large law firms to represent him in the civil rights case. Those firms, he said, found damages were minimal or nonexistent and the case wasn't worth their time. Greenberg Traurig's Kerri Barsh, a Miami shareholder and co-chair of the firm's environmental practice, was on the Supreme Court petition with Karlan.

The Supreme Court, ruling 7-2 in 2013, rejected the city's arguments that it could use admiralty law to seize and evict Lozman's floating home from the city's marina. Writing for the majority in one of his more colorful opinions, Justice Stephen Breyer said the floating structure was not a “vessel” under maritime law.

“But for the fact that it floats, nothing about Lozman's home suggests that it was designed to any practical degree to transport persons or things over water,” Breyer wrote. “It had no rudder or other steering mechanism. Its hull was unraked, and it had a rectangular bottom 10 inches below the water. It had no special capacity to generate or store electricity but could obtain that utility only through ongoing connections with the land. Its small rooms looked like ordinary nonmaritime living quarters. And those inside those rooms looked out upon the world, not through watertight portholes, but through French doors or ordinary windows.”

Unfortunately, by the time the court handed Lozman his legal victory, his floating home had been “arrested,” towed 80 miles and destroyed.

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., in an interview in 2013, said the floating home case was his “favorite” of the 2012-13 term.

The case in which the justices granted review Monday predates the fight over Lozman's floating home.

In early 2006, Lozman had moved to the city with his floating home and leased a slip in the municipally owned marina. Soon, he learned the city planned to redevelop the waterfront using eminent domain to seize thousands of homes and then transfer the land to a private developer, according to his petition. He was vocal in his opposition.

The day before the governor was to sign a bill barring the use of eminent domain for private development, the city council held a meeting to approve its agreement with the developers. Lozman sued, alleging the agreement was invalid because the council had violated the state's open-meetings law. The city council, in a closed-door meeting to discuss the lawsuit, decided to send Lozman “a message,” according to transcripts of the meeting later made public under state law.

During a public council meeting in November 2006, Lozman was recognized for comments at the public comment portion. He states in his petition that he was almost immediately cut off by the presiding member, and when he continued his comments, she urged his arrest. Lozman was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct and resisting arrest without violence. The state soon dropped the case.

Lozman filed a civil rights suit, alleging he was arrested in retaliation for speaking freely on public issues. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit in February affirmed the trial jury's finding that the arresting officer reasonably believed Lozman was committing or about to commit the offense of “disturbing a lawful assembly,” an offense with which he was never charged. The appellate court reiterated its rule that probable cause is an absolute bar to a false arrest claim—even when brought as a First Amendment retaliation claim.

That is now the issue before the Supreme Court: Does the existence of probable cause defeat a First Amendment retaliation claim? Four other appeals courts agree with the Eleventh Circuit; two circuits do not, and four others have no clear rule, according to his petition.

Lozman Finds Stanford Law's Appellate Clinic

When Lozman decided to go the Supreme Court with his fight over his floating home, he said, he did a Google search for “the best young Supreme Court practitioner.” The name of Jeffrey Fisher of Stanford Law School was prominent. Lozman said he emailed him and asked for representation.

“He said the school's [Supreme Court] clinic had a full docket, but he would represent me individually,” recalled Lozman. “Once cert was granted in that case, he said the clinic would represent me on the merits. After I lost the 11th Circuit appeal in this case, I sent him the opinion and said here's another circuit split and would the clinic be interested in representing me. He said yes.” (Fisher argued the case in October 2012 for Lozman.)

In his latest case, Lozman attracted support for his high court petition from the Institute for Justice, represented by Mayer Brown's Michael Kimberly, and the First Amendment Foundation, represented by Cathleen Hartge of Munger, Tolles & Olson.

The city's counsel in the high court is Jones Day appellate partner Shay Dvoretzky. Among other arguments, the city contends evidence of probable cause is readily available and critically important to determining whether an arrest really was retaliatory.

“I didn't like being arrested in 2006 and I didn't like my home being arrested in 2009,” Lozman said. “My grandfather fought in the trenches of World War I, my father and stepfather in World War II. I'm a former Marine. One of the things I love about this country is the personal freedom we have and the First Amendment is at the top of the list. I'm not going to let anyone take that away from me.”

The case is likely to be argued in late winter or early spring.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Law Firms Expand Scope of Immigration Expertise Amid Blitz of Trump Orders

6 minute read

Am Law 100 Lateral Partner Hiring Rose in 2024: Report

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250