'Troll King' Intellectual Ventures Wins Antitrust War With Capital One

U.S. District Judge Paul Grimm of Maryland seemed sympathetic to Capitol One but didn't endorse Capital One's novel antitrust argument.

December 04, 2017 at 07:30 PM

23 minute read

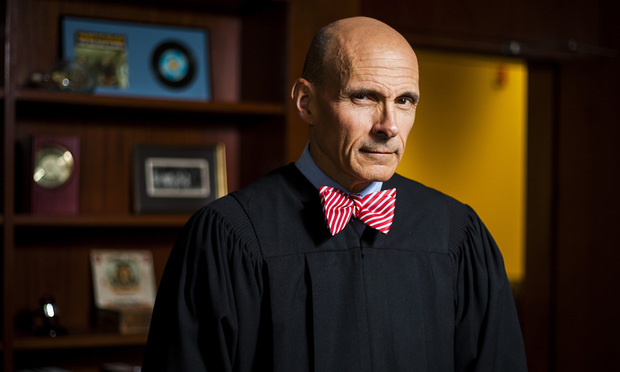

U.S. District Judge Paul Grimm. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM

U.S. District Judge Paul Grimm. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM Intellectual Ventures has shaken antitrust claims waged by Capital One Financial Corp. after four years of hard-fought litigation.

U.S. District Judge Paul Grimm of the District of Maryland turned back Capital One's argument that IV is violating antitrust laws by aggregating thousands of patents that read on financial industry technology and threatening to assert them seriatim until Capital One submits to an over-priced license. IV has asked Capital One for $131 million to license its entire portfolio for five years, though it maintains that was just an opening offer.

Attorneys for Capital One and other IV targets had hoped the novel antitrust argument might give them another tool for fighting the massive patent holding company that Grimm compared to Henrik Ibsen's “troll king” Dovregubben. Grimm seemed sympathetic at times in his 52-page order, issued Dec. 1. “It is hard to deny that there is something concerning from an antitrust perspective about the way in which IV engages in its licensing business,” the judge wrote at one point.

➤➤ Get IP news and commentary straight to your in-box with Scott Graham's email briefing, Skilled in the Art. Learn more and sign up here.

But under the Federal Circuit's interpretation of the relevant Supreme Court case law, IV is immune from Capital One's suit under the Noerr-Pennington doctrine, Grimm held. Noerr-Pennington shields lawsuits from antitrust claims so long as they're not “sham litigation.” Although IV hasn't prevailed in a patent case against Capital One or any other bank, its litigation against Capital One is not “baseless” and therefore doesn't meet the stringent Supreme Court standard for proving a sham, Grimm concluded.

Grimm added that a previous decision from U.S. District Judge Anthony Trenga of the Eastern District of Virginia rejecting nearly identical claims between the parties precluded Capital One from relitigating them in Grimm's court.

The Dec. 1 ruling is a huge win for IV and its team of attorneys at Feinberg Day Alberti & Thompson, led by Ian Feinberg; and Freitas Angell & Weinberg, led by Robert Freitas. Capital One is represented by a Latham & Watkins team headed by Matthew Moore, plus Troutman Sanders and Kirkland & Ellis.

A spokesman for Intellectual Ventures said the company would have no comment on the decision. A Latham spokeswoman referred a query to Capital One, which did not respond to a request for comment.

University of California, Hastings law professor Robin Feldman, whose scholarly critique of IV is quoted liberally in Grimm's opinion, said the decision “is not the end of the story. In fact, the decision foreshadows the battleground ahead.”

That battleground will feature the Federal Circuit, which she said has set the hurdle too high for antitrust cases against a patent holder. “The judge's clear and vibrant language, describing patent trolling, sets the stage for future litigants” to press their case at the Federal Circuit or the Supreme Court, Feldman said.

Grimm began his opinion by explaining the conundrum of the case. “A patent, by its very nature, vests its owner with a type of legal monopoly,” he wrote. “Enforcing a patent through litigation protects this monopoly, even though in other circumstances we view monopolies as harmful.” But while it's one thing to assert a handful of patents, “it is another matter to acquire a vast portfolio of patents that are essential to technology employed by an entire industry and then to compel its licensing at take-it-or-leave-it prices,” Grimm wrote.

Capital One actually succeeded on the merits of a primary argument, with Grimm finding the bank had raised a triable issue of fact as to whether IV's portfolio of financial industry patents constitutes a relevant market for antitrust purposes. “While fact-finders ultimately might reject [Capital One's expert's] reliance on cluster markets to justify her antitrust market analysis, I cannot conclude that as a matter of law it is unreasonable,” Grimm wrote.

But the case foundered on Noerr-Pennington. Capital One had urged Grimm to look beyond IV's litigation conduct and consider its entire alleged “scheme” of aggregating patents, concealing them in shell companies, and bringing repetitive suits to extract supra-competitive license prices.

But Grimm pointed to Professional Real Estate Investors v. Columbia Pictures, in which the Supreme Court ruled that if an antitrust defendant has probable cause to file suit, the sham litigation exception does not apply. Grimm noted that Justice John Paul Stevens had written separately in that case to say that “repetitive filings, some of which are successful and some unsuccessful, may support an inference that the process is being misused.” But the Supreme Court majority did not adopt that caveat, Grimm pointed out.

Instead, Grimm had to focus on the case before him, which began as a patent suit by IV. Although Grimm ultimately had ruled the handful of patents IV was asserting were non-infringed, invalid or ineligible, he said it was clear IV had had probable cause to file the suit for several reasons. An experienced special master had originally recommended that two patents be found eligible, for one. “This fact alone is sufficient to show that a reasonable litigant could realistically expect to succeed on the merits,” Grimm wrote. Plus, patents are presumed valid, the suit was filed before the Supreme Court tightened eligibility requirements in Alice v. CLS Bank, and IV incurred substantial costs in litigating the case, including the hiring of nine expert witnesses.

“This is an opinion that relies on the facts of the case such as a pre-Alice filing, special master report, nine experts, and a similar case in another jurisdiction,” said Rutgers antitrust and IP professor Michael Carrier. “There could be a successful suit in the future against an entity like IV but the facts would need to be different.”

U.S. District Judge Paul Grimm. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM

U.S. District Judge Paul Grimm. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM Intellectual Ventures has shaken antitrust claims waged by

U.S. District Judge Paul Grimm of the District of Maryland turned back

Attorneys for

➤➤ Get IP news and commentary straight to your in-box with Scott Graham's email briefing, Skilled in the Art. Learn more and sign up here.

But under the Federal Circuit's interpretation of the relevant Supreme Court case law, IV is immune from

Grimm added that a previous decision from U.S. District Judge Anthony Trenga of the Eastern District of

The Dec. 1 ruling is a huge win for IV and its team of attorneys at Feinberg Day Alberti & Thompson, led by Ian Feinberg; and Freitas Angell & Weinberg, led by Robert Freitas.

A spokesman for Intellectual Ventures said the company would have no comment on the decision. A Latham spokeswoman referred a query to

University of California, Hastings law professor Robin Feldman, whose scholarly critique of IV is quoted liberally in Grimm's opinion, said the decision “is not the end of the story. In fact, the decision foreshadows the battleground ahead.”

That battleground will feature the Federal Circuit, which she said has set the hurdle too high for antitrust cases against a patent holder. “The judge's clear and vibrant language, describing patent trolling, sets the stage for future litigants” to press their case at the Federal Circuit or the Supreme Court, Feldman said.

Grimm began his opinion by explaining the conundrum of the case. “A patent, by its very nature, vests its owner with a type of legal monopoly,” he wrote. “Enforcing a patent through litigation protects this monopoly, even though in other circumstances we view monopolies as harmful.” But while it's one thing to assert a handful of patents, “it is another matter to acquire a vast portfolio of patents that are essential to technology employed by an entire industry and then to compel its licensing at take-it-or-leave-it prices,” Grimm wrote.

But the case foundered on Noerr-Pennington.

But Grimm pointed to Professional Real Estate Investors v. Columbia Pictures, in which the Supreme Court ruled that if an antitrust defendant has probable cause to file suit, the sham litigation exception does not apply. Grimm noted that Justice John Paul Stevens had written separately in that case to say that “repetitive filings, some of which are successful and some unsuccessful, may support an inference that the process is being misused.” But the Supreme Court majority did not adopt that caveat, Grimm pointed out.

Instead, Grimm had to focus on the case before him, which began as a patent suit by IV. Although Grimm ultimately had ruled the handful of patents IV was asserting were non-infringed, invalid or ineligible, he said it was clear IV had had probable cause to file the suit for several reasons. An experienced special master had originally recommended that two patents be found eligible, for one. “This fact alone is sufficient to show that a reasonable litigant could realistically expect to succeed on the merits,” Grimm wrote. Plus, patents are presumed valid, the suit was filed before the Supreme Court tightened eligibility requirements in Alice v. CLS Bank, and IV incurred substantial costs in litigating the case, including the hiring of nine expert witnesses.

“This is an opinion that relies on the facts of the case such as a pre-Alice filing, special master report, nine experts, and a similar case in another jurisdiction,” said Rutgers antitrust and IP professor Michael Carrier. “There could be a successful suit in the future against an entity like IV but the facts would need to be different.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Antitrust in Trump 2.0: Expect Gap Filling from State Attorneys General

6 minute read

Private Equity Giant KKR Refiles SDNY Countersuit in DOJ Premerger Filing Row

3 minute read

Skadden and Steptoe, Defending Amex GBT, Blasts Biden DOJ's Antitrust Lawsuit Over Merger Proposal

4 minute read

FTC Sues PepsiCo for Alleged Price Break to Big-Box Retailer, Incurs Holyoak's Wrath

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Who Are the Judges Assigned to Challenges to Trump’s Birthright Citizenship Order?

- 2Litigators of the Week: A Directed Verdict Win for Cisco in a West Texas Patent Case

- 3Litigator of the Week Runners-Up and Shout-Outs

- 4Womble Bond Becomes First Firm in UK to Roll Out AI Tool Firmwide

- 5Will a Market Dominated by Small- to Mid-Cap Deals Give Rise to a Dark Horse US Firm in China?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250