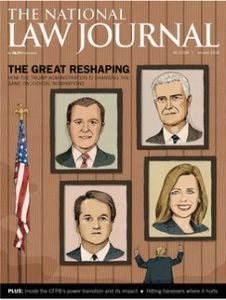

The Great Reshaping: How Trump Is Changing the Game on Judicial Nominations

With 148 judicial vacancies as of Jan. 2 and an increasingly aging federal bench, President Donald Trump could remake the federal judiciary on a scale that hasn't been possible in decades.

January 02, 2018 at 03:28 PM

12 minute read

President Donald Trump walks from the west wing of the White House to Marine One before heading to Joint Base Andrews and on to Bedminster, NJ, Friday, August 4, 2017.

President Donald Trump walks from the west wing of the White House to Marine One before heading to Joint Base Andrews and on to Bedminster, NJ, Friday, August 4, 2017.

Conservatives have been waiting for this opportunity for years.

Conservatives have been waiting for this opportunity for years.

With 148 judicial vacancies as of Jan. 2 and an increasingly aging federal bench, President Donald Trump could remake the federal judiciary on a scale that hasn't been possible in decades. The president is poised to shift the federal courts dramatically to the right by filling them with a new generation of young, conservative jurists.

Trump got 19 of his Article III nominees confirmed in 2017, including 12 to sit on courts of appeals and one U.S. Supreme Court justice. While President Barack Obama also had appointed a Supreme Court justice at this point, Trump has quadrupled the number of appellate appointees Obama had at this point in his first term, with twelve to Obama's three.

Trump's early nomination numbers also fare well when compared with Trump's closest Republican predecessor, President George W. Bush. Though Bush had 18 nominees confirmed by the same point in his presidency, only five had been confirmed for appellate courts.

As Ilya Shapiro, a scholar at the libertarian Cato Institute put it, Trump's nominees aren't a ragtag group of Republican “political hacks.”

Trump and White House counsel Don McGahn promised voters that nominees will be committed to originalism and textualism. That means that their rulings are expected to interpret the Constitution as they believe the original framers meant and primarily base their statutory interpretations on the plain text of the laws.

McGahn is also a member of the Federalist Society, as are many of Trump's nominees. The organization and the Heritage Foundation, serve as conservative “feeder” sources for the administration's nominees.

What else do Trump's nominees have in common? They trend younger, on average, than nominees in years past. The average age of the first nine Trump appointees confirmed to appellate courts is 44.

In contrast, more than 50 percent of active judges on U.S. circuit courts were at least 50 years old at the time of their appointment, as of June 1, according to a Congressional Research Service report.

The number of appellate vacancies is also likely to increase as judges grow older and retire in the next few years. Under the law, federal judges can, as early as 65, retire at their current salaries or take senior status. More than half of all active federal appellate court judges were 65 years or older, as of June 1, according to the CRS.

Ed Whelan, a former clerk to Justice Antonin Scalia and president of the conservative nonprofit Ethics and Public Policy Center, said the Trump administration is tapping a new generation of legal thinkers who embrace originalism more exuberantly than their predecessors.

“These are people who are now in the prime of their career, and there's a lot of them with outstanding credentials,” Whelan said. “So there's lots of great folks to choose from. It's not simply that it's a new generation, but it's a larger group too.”

Trump's judicial nominees, overall, represent a range of professional experiences. As of August, according to a CRS report issued that month, 10 of Trump's first 26 judicial nominees were working as attorneys in private practice immediately prior to being nominated, and 10 were working as federal or state judges. That's the greatest number of private practice attorneys of the past four presidents' first 26 nominees and the lowest number of working judges, according to the CRS.

Judging the Crop

Most conservative lawyers interviewed for this story said Trump's appellate nominees, which include private attorneys, judges and professors, are extremely qualified.

Many have prior judicial experience. Amul Thapar, Trump's first appellate nominee, served on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky before he took his seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit on May 25. There also are several state Supreme Court justices, such as Don Willett of Texas, confirmed to the Fifth Circuit Dec. 18, and Joan Larsen of Michigan, who was confirmed to the Sixth Circuit on Nov. 1.

Some are advocates. Kyle Duncan, a Fifth Circuit nominee, was the first solicitor general of Louisiana; and Greg Katsas, now on the powerful D.C. Circuit, worked in the White House Counsel's office until his confirmation.

There are also law professors, like Amy Coney Barrett from Notre Dame Law School, who now sits on the Seventh Circuit, and Stephanos Bibas from the University of Pennsylvania on the Third Circuit.

“The thinking is that courts are important. Judicial nominations are for life,” Shapiro said. “This is a huge way for an administration to make an impact.”

“The quality of these nominees, as well as their youth, beats any Republican president, including George W. Bush,” Shapiro continued. “This is the best judicial nomination operation that we've seen in modern times.”

Despite the support from conservative legal observers, Trump's nominees have not been without controversy. Three of his nominees failed to get past their initial confirmation hearings following controversies over their lack of trial experience, incendiary rhetoric or apparent lack of familiarity with basic litigation terms.

Abandoning Norms?

Trump's judicial nomination machine concerns many Democrats and liberal advocacy groups. They oppose the president's nominees, not only because of their personal opinions or ideological positions but also because of what they say is the White House's abandonment of norms intended to ensure judges are well-qualified and ethical. They say that includes Trump's decision to publicly reveal the names of those he's considering for Supreme Court slots before choosing a nominee, a failure to prioritize diversity, the White House's refusal to work with the American Bar Association in vetting nominees, and speeding nominees through the Senate confirmation process.

Compounding the concern is the fact that courts have blocked several of Trump's key policies, including his travel bans or the ban on transgender people serving in the military, said Kyle Barry, policy counsel at the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund.

“The combination of the nominees who Trump has put forward and the willingness of the Senate Republican leadership to dismantle the norms in the process to get these people confirmed as soon as possible poses an enormous threat to the rule of law, to the independence of courts and to our federal judiciary itself,” Barry said.

Conservatives tout Trump's Supreme Court list–first released in May 2016 and later updated several times–as a transparent promise to voters. Some, including Shapiro, said Trump would not have been elected without it. But those on the more liberal side, like Lena Zwarensteyn, director for strategic engagement at the American Constitution Society, said the list creates ethical issues because it signals to judges that they're being watched and prompts them to rule certain ways.

Powerful appellate judges are on that list, like D.C. Circuit Judge Brett Kavanaugh. He's likely to encounter another Trump-related case before the next Supreme Court vacancy comes up due to his position in Washington, where the appeals court's docket includes a significant number of government-related cases. In October, Kavanaugh was on a three-judge panel and later an en banc bench considering whether the Trump administration was illegally blocking an undocumented immigrant teenager from obtaining an abortion. Kavanaugh dissented from the en banc opinion that allowed the girl to obtain the procedure.

Diversity and Distrust

Michele Jawando, vice president of legal progress at the liberal Center for American Progress, worked on judicial nominations in the Senate during the Obama years. She said another issue is what the list signals to those who aren't on it.

“The concern about a list is, you look at that list, and you realize you're not on that list,” Jawando said. “Do I perhaps rewrite an opinion with different expectations of who will read it? Do I signal to different organizations that I adhere to a certain ideology or philosophy?”

Jawando also pointed to the lack of diversity in the nominees so far. More than 90 percent are white, and more than 80 percent are male, as of Dec. 1, a vast change from President Barack Obama's administration, which prioritized judicial diversity. Of Obama's 329 judicial appointees, 37 percent were white and about 58 percent were male.

A lack of diversity leads to distrust of the judiciary, Jawando said.

“Not having a diverse judiciary impacts us greatly,” she said. “I think it's something we don't talk enough about and it is, quite frankly, something that we should all worry about in terms of how our communities are going to interact with one another.”

Some conservative lawyers, like Whelan, said not enough minority groups agree with the textualist or originalist approach.

“I'd say it's a shame that there aren't more African-Americans and Hispanics who are judicial conservatives,” Whelan said.

Carrie Severino, the chief counsel at the Judicial Crisis Network, an organization that supports conservative judicial nominees, said liberals are taking a narrow view of diversity when they bring up race or gender.

She used the example of Barrett, questioning how many women with high-profile careers like hers also raised seven children while working, as she did. She also pointed to Willett, the son of a single mother who grew up in a trailer park.

“The most important thing is, as Martin Luther King, Jr. would have said, not the color of anyone's skin but the content of their character,” Severino said. “In this case, it's the judicial philosophy that they bring to the court.”

Another broken norm is the White House's decision not to involve the American Bar Association in vetting nominees prior to their announcement, as Obama did. Obama did not nominate anyone who was publicly rated by the ABA as “not qualified.”

Under Trump, the ABA instead finds out who the nominees are when they're announced. As of Dec. 1, four nominees have been rated “not qualified.” That's half as many as Bush had in eight years with a similar approach to the ABA.

Republican senators and conservatives question the ABA's methods and importance. Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, recently called the organization a liberal advocacy group, adding its “not qualified” ratings aren't warranted. Pam Bresnahan, the chair of the ABA's vetting committee and a partner at Vorys, Sater, Seymore and Pease, said ABA ratings are based solely on interviews with nominees' peers.

“[Our process] works the same for the 'well-qualifieds' as the 'qualifieds' and the 'not qualifieds,'” Bresnahan said. “It doesn't change based on the rating. That's why they have faulty logic on it.”

Bresnahan added that while Bush used a similar process to Trump, the ABA's relationship with the White House was more “collegial” in that previous administration.

Senate disagreements over nominee vetting are partly a result of increasing partisanship, scholars said. While Bush's first nine appellate nominees that were confirmed garnered at least 93 “yes” votes from senators, only one of Trump's, Ralph Erickson for the Eighth Circuit, received more than 66 “yes” votes—he received 95. Carl Tobias, a University of Richmond Law School professor, said quibbling over issues like ABA vetting or home state approval of nominees distracts from lawmakers' role in investigating nominees.

“The process is on a downward spiral,” Tobias said. “It just shows you how partisan the process has been and is continuing to be. You can always find data that will support something that you want to do, and it's sort of devolved into that.”

But all the fighting over the nomination process could reach new heights or come to a halt next year, depending on whether Democrats win a majority in the Senate in 2018.

Until then, conservatives will continue to cheer as the Trump administration charges forward.

“This story of judicial nominees—whatever else is happening in the Trump administration—is really remarkable,” Shapiro said. “It's hard to imagine that a more conventional Republican would have had any more success than Trump is having, and that's very interesting.”

Editor's note: This online version of the NLJ's January cover story has been updated to reflect both new judicial confirmations since our print edition went to press in early December and nominees that withdrew from the nomination process since that point.

Correction: Ed Whelan's name has been corrected from an earlier version of this story.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Federal Judge Pauses Trump Funding Freeze as Democratic AGs Plan Suit

4 minute read

Judges Split Over Whether Indigent Prisoners Bringing Suit Must Each Pay Filing Fee

Supreme Court Agrees to Hear Lawsuit Over FBI Raid at Wrong House

4th Circuit Upholds Virginia Law Restricting Online Court Records Access

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Is It Time for Large UK Law Firms to Begin Taking Private Equity Investment?

- 2Federal Judge Pauses Trump Funding Freeze as Democratic AGs Launch Defensive Measure

- 3Class Action Litigator Tapped to Lead Shook, Hardy & Bacon's Houston Office

- 4Arizona Supreme Court Presses Pause on KPMG's Bid to Deliver Legal Services

- 5Bill Would Consolidate Antitrust Enforcement Under DOJ

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250