Sotomayor Renews Call for Experienced Criminal Defense Advocates

When those advocates miss an important line of argument or are drawn by the justices' questions into taking an unhelpful position, Sotomayor said she may pass a note to a colleague, saying, "I want to kill them."

January 29, 2018 at 03:29 PM

4 minute read

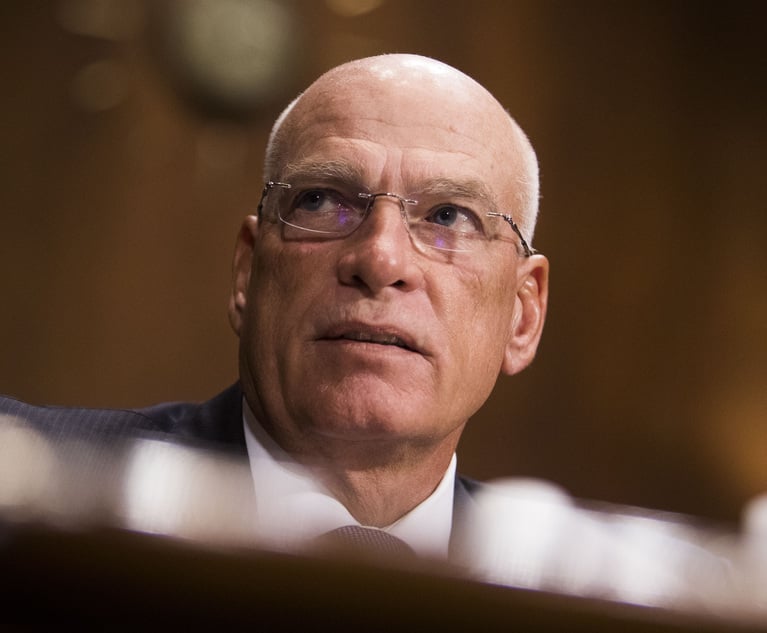

Sonia Sotomayor testifies in 2009 at her confirmation hearing. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

Sonia Sotomayor testifies in 2009 at her confirmation hearing. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

Last fall, Justice Elena Kagan touted the advantages of an experienced U.S. Supreme Court Bar—the “repeat players” who know what the court likes. Justice Sonia Sotomayor seems to think criminal defense lawyers still aren't getting the message.

During a visit at the University of Houston Law Center, Sotomayor voiced her frustration with criminal defense lawyers who don't have the skills of a practiced Supreme Court advocate.

When those advocates miss an important line of argument or are drawn by the justices' questions into taking an unhelpful position, Sotomayor said she may pass a note to a colleague, saying, “I want to kill them.”

Sotomayor's remarks reflect her long-standing concern about criminal defense lawyers who are first-timers in high court arguments. In a 2014 Reuters article, she was asked why so few Supreme Court advocates argue on behalf of criminal defendants. The justice said many criminal defense lawyers are reluctant to give up their moment in the spotlight of a high court argument.

“I think it's malpractice for any lawyer who thinks, 'This is my one shot before the Supreme Court, and I have to take it,'” she said then.

During a U.S. Justice Department event that same year on the legacy of Gideon v. Wainwright, Kagan shared similar sentiments, saying, “Case in and case out, the category of litigant who is not getting great representation at the Supreme Court are criminal defendants.”

Sotomayor's frustrations reflect her own experiences with criminal trials. She is the high court's only former trial judge. She brings to the bench an eagle eye on how criminal trials play out in the real world and what is expected of both the defense and the prosecution. Even if an experienced appellate advocate is before her, she does not hesitate to call out the lawyer if he or she is playing fast and loose with how a trial or sentencing proceeding should operate.

Lamenting the lack of diversity on the high court itself, Sotomayor said in 2013 she was bothered by the fact judges rarely come to the bench from the defense bar or with civil rights experiences. “We're missing a huge amount of diversity on the bench,” she said.

A 2016 study by Harvard Law School's Andrew Crespo analyzed what he called the high court's institutional shift over the last four decades toward the prosecution. One part of that shift, Crespo found, was the “rise of a sharp advocacy gap between criminal defendants and the rest of the increasingly expert Supreme Court bar, including expert advocates for the prosecution.”

Two veteran high court advocates who occasionally step into that gap on behalf of criminal defendants are former Clinton administration U.S. Solicitor General Seth Waxman of Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr, who often handles death row appeals, and Stanford Law School's Jeffrey Fisher.

And there have been efforts to prepare the criminal defense attorney making a first appearance before the high court. Some law schools with Supreme Court clinics offer moot court and other preparation help. The law firm Sidley Austin has for years conducted a pro bono program to assist federal public defenders with Supreme Court cases.

That an experienced Supreme Court advocate is an invaluable asset in a case before the high court was evident in Kagan's comments last fall at the University of Wisconsin School of Law.

Kagan said many high court arguments are made by “repeat players,” members of an “extremely high caliber bar,” who “really know the court, who know the process of arguing before the court, who know what it is we like, who know what they should be doing, what they shouldn't be doing.”

Read more:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Paul Weiss’ Shanmugam Joins 11th Circuit Fight Over False Claims Act’s Constitutionality

‘A Force of Nature’: Littler Mendelson Shareholder Michael Lotito Dies At 76

3 minute read

US Reviewer of Foreign Transactions Sees More Political, Policy Influence, Say Observers

'Unlawful Release'?: Judge Grants Preliminary Injunction in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Authenticating Electronic Signatures

- 2'Fulfilled Her Purpose on the Court': Presiding Judge M. Yvette Miller Is 'Ready for a New Challenge'

- 3Litigation Leaders: Greenspoon Marder’s Beth-Ann Krimsky on What Makes Her Team ‘Prepared, Compassionate and Wicked Smart’

- 4A Look Back at High-Profile Hires in Big Law From Federal Government

- 5Grabbing Market Share From Rivals, Law Firms Ramped Up Group Lateral Hires

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250