Fearing DLA Piper-Style Breach, DC Firms Ramp Up Cyber Defenses

Months after a crippling malware attack on one of the world's largest law firms made global headlines, firms in the nation's capital say they're doing everything they can to fend off a similar crisis.

February 22, 2018 at 03:05 PM

8 minute read

Alarmed by the rising threat of hackers bent on extorting, exposing or undermining their work, Washington, D.C., law firms have been quietly changing their behavior since DLA Piper fell victim to a major security breach last June.

DLA Piper's D.C. leader, meanwhile, says the firm has emerged stronger than ever from the crisis.

It's been about eight months since a cyberattack briefly crippled the 3,600-lawyer megafirm's operations—and nearly two years since attacks on Cravath, Swaine & Moore, Weil, Gotshal & Manges and other firms first went public. Since then, firms in the nation's capital have quickened their behind-the-scenes efforts to thwart and respond to such attacks.

Law firms that didn't have cyber insurance immediately began purchasing coverage after the DLA Piper breach, and large firms with cyber insurance increased their coverage, said Tom Ricketts, a senior vice president and executive director at insurance brokerage Aon Risk Solutions.

Ricketts said the June attack, which paralyzed some other global business as well, had a “dramatic impact” on Aon's business. In the final six months of 2017, Aon's client base of law firms purchasing cyber insurance grew 10 percentage points, he said, adding that the medium limit of insurance purchased by firms with more than 500 attorneys grew from $10 million to $20 million since last summer.

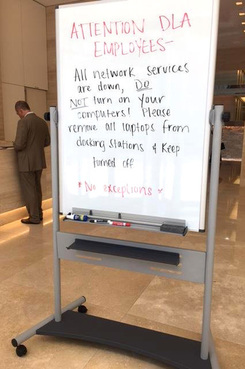

A sign greeting DLA Piper's Washington employees on June 27, 2017. Photo: Eric Geller/Politico

A sign greeting DLA Piper's Washington employees on June 27, 2017. Photo: Eric Geller/Politico

Even more than their counterparts outside the capital, the political nature of the work at many D.C. firms may put them in hackers' crosshairs. That was true even before a growing number of private lawyers and their firms became deeply involved in special counsel Robert Mueller's probe of alleged Russian meddling in the 2016 election. And while it didn't involve breaches at the firms themselves, the hack and leak of Democratic National Committee emails during the 2016 presidential campaign included correspondence with lawyers at multiple firms.

Firms in D.C. and elsewhere are particularly concerned about an attack worse than the one DLA Piper faced, caused by a “zero day” virus that could bring a firm to its knees. A zero-day virus refers to malware relying on a software vulnerability for which no fix yet exists.

Like other businesses, law firms have seen the rate of attempted cyberattacks grow rapidly in recent years and months, leading some firm leaders to decline to talk about the topic for fear of placing a target on their back. One Washington-based firm told The National Law Journal the number of attempted daily cyberattacks it witnessed increased 500 percent in just the last two years.

'An Act of War'

At DLA Piper, the fallout over the cyberattack last June may have settled, but the firm has made permanent changes in its wake.

The attackers knocked the firm's phones down and rendered its computers useless in most of its offices worldwide. Lawyers entering the firm's D.C. offices during the attack were greeted by a message on a whiteboard instructing them not to turn on their computers. A statement from the firm nearly two weeks after the attack showed that some of its systems were still being restored at the time.

Jeff Lehrer, managing partner of DLA Piper's D.C. and northern Virginia offices, said that in the months since, his firm has returned to developing hard-copy printouts of phone numbers and other information needed for the firm to continue functioning in case of a cyber crisis.

Lehrer, who said the firm has made many improvements to its infrastructure and systems, told The National Law Journal that DLA Piper was the victim of a geopolitical conflict originating on the other side of the globe.

“It was an act of war against the Ukraine, and we happen to have a Ukraine office,” Lehrer said. “One of the negatives of being global is that we had a Ukraine office. So if you didn't have a Ukraine office, you wouldn't have been subject to this. And the person who [inadvertently triggered the virus] happened to, had to have been an administrator with administrative privileges. So it took that as well to spread it.”

The attack came via an update to accounting software unique to Ukraine that was necessary to submit tax filings, Lehrer said. After one DLA Piper user with administrative privileges opened the program, the firm's connected operations around the world became infected with the virus that Lehrer said used “technology that came from the NSA.”

National Security Agency spokeswoman Kelly Biemer responded to questions about Lehrer's claim in an email, stating, “We're not able to discuss allegations regarding intelligence activities.” She pointed to a White House press secretary statement from Feb. 15, 2018, that said, “In June 2017, the Russian military launched the most destructive and costly cyberattack in history.”

While initial reports suggested the virus was so-called “ransomware,” intent on extorting payment from affected users for access to their devices, Lehrer said the cyberattack was not ransomware but an attack designed to shut things down. Lehrer said “no data was lost” by DLA Piper as a result of the attack.

The malware harming DLA Piper appears to have been a variant of the malware “Petya,” which some analysts dubbed “NotPetya,” that hit businesses around the globe including companies in the shipping and health care industries.

Unlike earlier iterations of Petya attacks, where ransomware was deployed seeking to extort affected users, the new malware was reported to be more of a “wiper” that mimics ransomware but is designed to wreak havoc, not extract a ransom.

Lehrer said that in the end, the crisis left DLA Piper in a better position to serve its clients. He said he thinks clients appreciate that the firm's lawyers are better advisers in the cybersecurity realm because of their firsthand experience, and the firm was able to more than overcome the financial impact.

“That was a horrible experience, what we went through,” Lehrer said. “And despite that, we still beat budget. So it was a good morale booster in that even though we lost some important billing time and down cycle, the firm still was doing so well economically that even despite that loss of revenues for a certain period of time, we still beat budget.”

Lehrer said the D.C. office also had plenty to celebrate last year, with low attrition and plans to grow in the Washington market. DLA Piper is moving forward with its plans to grow its footprint in Washington to better match some of its competition's scale in the nation's capital. The other good news amid setbacks caused by the cyberattack that hit the firm in 2017, Lehrer said, is the rate of attrition among partners in DLA Piper's D.C. office last year was among its lowest numbers in the preceding 10 years.

Local Lessons

Crowell & Moring firm chair Phil Inglima said his 400-plus lawyer firm has long made cybersecurity a top priority. But the malware attack on DLA Piper still appears to have come as a surprise.

“I think that it's been a wake-up call to everybody in the legal community, and probably there are many firms that say, 'There but for the grace of God go I,'” Inglima said. “But I do think that we've done a very good job of developing the maximum defenses that we can in the time that we've had this kind of awareness and vulnerability of IS [information services] systems.”

Arent Fox chief technology office Ed Macnamara said DLA Piper's experience offered a case study to illustrate to firm leadership the dangers they face.

“It really is an escalating war going on every day,” Macnamara said.

The direct and indirect victims of cyberattacks can range from large firms with several thousand attorneys to small shops with just a handful of lawyers.

A study by the startup cybersecurity consulting firm LogicForce from 2017's fourth quarter found that hackers wielding malware prey on vulnerabilities that are “commonplace” throughout the legal industry.

“Law firms should not take comfort in thinking they may be too small or remote to be victimized,” the report warned. “The event that impacted DLA Piper and innumerable other businesses would likely have affected thousands of law firms in the U.S. if it wasn't primarily a regional event.”

Austin Berglas, global head of cyber forensics and incident response at cyber defense practice BlueVoyant, also said he has witnessed firms increasing their investments in cyber defense. He said firms should also proactively work with public relations firms as part of their response planning, to minimize the reputational risks an attack can bring.

“More firms are asking for the development and updating of their IR [incident response] plans and taking some lessons learned from the [DLA] Piper incident,” especially when it comes to maintaining communications amid an attack, said Berglas, a former head of the FBI's cyber branch in New York.

“Most importantly, they're starting to realize they're not immune,” he said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

FTC's Info Security Action Against GoDaddy Sends 'Clear Signal' to Web Hosting Industry: Expert

Does the Treasury Hack Underscore a Big Problem for the Private Sector?

6 minute read

Insurance Policies Don’t Cover Home Depot's Data Breach Costs, 6th Circuit Says

Trending Stories

- 1We the People?

- 2New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 3No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 4Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 5Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250