SCOTUS and the Road Ahead for Travel Ban 3.0

Immigrants' rights advocates square off against the government on whether the ban violates the U.S. Constitution and immigration law.

February 28, 2018 at 06:00 PM

9 minute read

After multiple defeats of its so-called travel ban in the lower courts, the Trump administration makes a final stand in April in what may be less hostile territory—the U.S. Supreme Court.

Since the administration's first effort to suspend the entry of foreign nationals from seven predominantly Muslim nations a little more than a year ago, the Supreme Court seemed the inevitable arbiter of the constitutional and statutory challenges to the administration's goal.

In the time since the administration's first effort triggered chaos at airports here and abroad, the travel ban has provoked mass protests, presidential attacks on federal judges, a volunteer lawyer movement, an alliance between business, civil rights and religious groups and even an original series by Spotify—”I'm with the Banned“—featuring new music and videos by artists from the six largely Muslim countries included in the latest travel ban.

Here is a quick look at the path to the high court, the lawyers and what the justices face in April:

What Makes Travel Ban 3.0 Different From 1.0 and 2.0?

Unlike the first two executive orders, the government argues that the president issued his third order after an “extensive, worldwide review by multiple government agencies” of whether foreign governments provide sufficient information to allow the United States to screen aliens seeking to enter this country. That type of review was missing from the first two orders. There also is no end date to the ban in its latest reiteration.

“Whereas prior orders of the President were designed to facilitate the review, the Proclamation directly responds to the completed review and its specific findings of deficiencies in particular countries,” the government's solicitor general, Noel Francisco, tells the court in the government's petition.

Hawaii and other challengers to the latest order are not persuaded. Travel ban 3.0, they counter, is a direct descendant of the earlier two bans. “The order continues, and makes indefinite, substantially the same travel ban that has been at the core of all three executive orders,” writes Hogan Lovells' Neal Katyal in his response for the challengers.

Francisco and former Obama administration acting Solicitor General Katyal are expected to face off in the April arguments.

How Did We Get Here?

An argument on the travel ban policy before the high court feels like it's been a while in the making. Trump first promised a version of the travel ban before he even became the GOP nominee. In December 2015, Trump tweeted a press release urging a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” A little more than a year later, on Jan. 27, 2017, the president issued the first travel ban executive order, barring entry for 90 days of citizens from seven majority-Muslim countries.

Lawsuits followed almost immediately, and lawyers swarmed airports to help stranded immigrants amid the chaos. In response to a lawsuit brought by the state of Washington, a federal district court there issued a nationwide temporary restraining order blocking the ban, and a three-judge panel at the Ninth Circuit upheld the TRO days later.

Despite Trump's Twitter promise to return to the courtroom, the administration never appealed the decision, opting instead to issue a second order on March 6. Tailored to address the Ninth Circuit's concerns, the second order dropped a country from the list, included a delayed effective date and initiated the worldwide review that would become central to the third ban.

Lawsuits again followed. Federal judges in Hawaii and Maryland blocked the order by mid-March and the Fourth and Ninth circuits upheld those injunctions in June. The Justice Department appealed both decisions to the Supreme Court, which scheduled an October argument and stayed the injunctions except with respect to immigrants with “bona fide” relationships to the U.S.

When the second travel ban order expired in September, Trump issued a proclamation implementing the third iteration of the band, and the justices took the October argument off the argument calendar. The following month, the cases, now considered moot, were taken off the docket entirely. The underlying Fourth and Ninth Circuit opinions were vacated without any comment on the merits.

The third travel ban followed the same legal path as the second, with the plaintiffs in Hawaii and Maryland filing amended complaints. The same district judges who blocked the second ban blocked the third, but it didn't last long. The Supreme Court stepped in early, staying the injunctions and allowing the ban to go into effect while the cases continued.

In late December, the Ninth Circuit took its third swipe at the travel ban, citing Justice Frank Murphy's dissenting opinion in Korematsu v. United States.

“All residents of this nation are kin in some way by blood or culture to a foreign land.'” the opinion repeated. “It cannot be in the public interest that a portion of this country be made to live in fear.”

As of Feb. 6, the Fourth Circuit, which heard the case en banc, had yet to issue an opinion in the Maryland case. Still, on Jan. 19, the Supreme Court granted the government's petition in the Hawaii case, agreeing for the second time to take up the travel ban.

Issues Before the Justices

The high court faces statutory and constitutional questions. But first, the justices must decide whether, as the government claims, the president's decision to exclude or deny a visa to an alien is not subject to judicial review. If the justices agree, that could be the end of the case.

Second, did the president, in issuing his order, exceed his authority under federal immigration law?

Third, was the nationwide injunction against enforcing the travel ban, except for aliens from two of the eight countries, overbroad? The government tells the justices that the injunction here “continues a deeply troubling trend in the lower courts of entering relief that extends well beyond the parties.”

And finally, the justices directed both sides to brief and argue whether the travel ban violates the First Amendment's establishment clause by discriminating on the basis of religion.

Outside Interests

Since its first issuance, the travel ban drew the ire of businesses, universities and others who claimed the policy would cause chaos.

Though no amicus briefs had been filed in the current case at the Supreme Court as of Feb. 5, briefs flooded the high court when arguments over the second travel ban order were pending there. More recently, several briefs were filed in the Ninth Circuit as that court considered the third travel ban.

Mayer Brown partners Andy Pincus and Paul Hughes, who helped stranded immigrants at the airport in the wake of the first travel ban order, filed a brief with the Ninth Circuit on behalf of more than 100 technology companies, including Amazon, Google, Facebook and Microsoft.

The travel ban, they wrote, hinders American companies' ability to attract talent, increases their costs, curbs international competition and encourages global companies to expand abroad, instead of inside the U.S. Pincus and Hughes argued the indefinite nature of the third travel ban, and the potential for the administration to make further changes to the policy at will, create instability for businesses.

“The continuing risk of additional, unanticipated changes in immigration rules creates significant uncertainty that imposes a substantial burden on managing global businesses and planning for the future,” the brief said.

Others who jumped in at the Ninth Circuit included former Associate Attorney General and Jenner & Block partner Tom Perrelli on behalf of more than two dozen universities and Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld's Pratik Shah, partner, and Martine Cicconi, counsel, for the Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality and other civil rights organizations.

Justices to Watch

Although the Trump administration's arguments supporting the travel ban have failed in the lower courts, the administration did get some good news on Dec. 4 when the justices, with two dissenting, allowed the ban to be enforced fully, pending action on the government's petition. Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor indicated they would have denied the government's request. The court's action went further than its partial lifting of an injunction against travel ban 2.0 last June. That would seem to bode well for the government, but it's not wise to bet on the ultimate outcome.

Not surprisingly, Justice Anthony Kennedy may be key here. The concept of individual dignity is at the core of his jurisprudence, and arguments that the order discriminates on the basis of nationality or religion may resonate with him.

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. also may play an important role. He has a keen interest in the constitutional structure and allocation of powers. That interest undoubtedly will bear on his interpretation of presidential authority under the immigration law provisions at the heart of the statutory claims.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

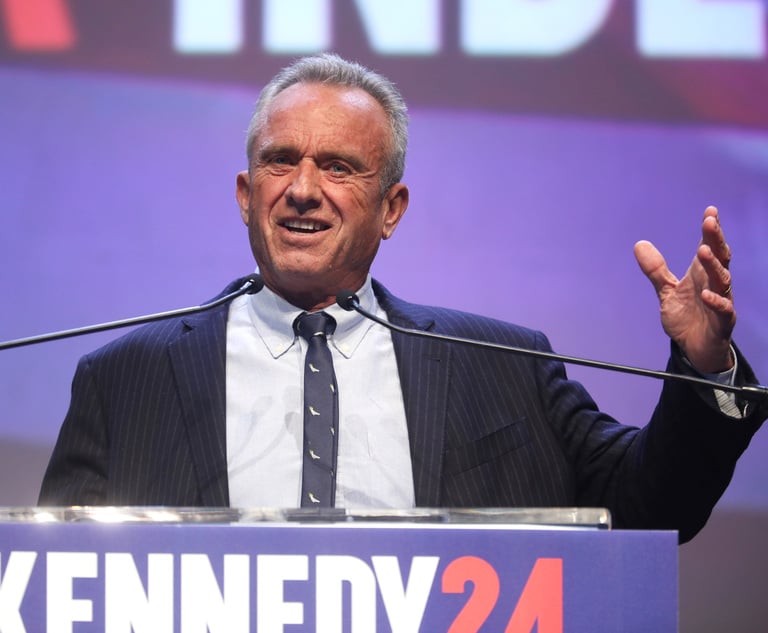

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Trump Administration Faces Legal Challenge Over EO Impacting Federal Workers

3 minute read

'Something Else Is Coming': DOGE Established, but With Limited Scope

US DOJ Threatens to Prosecute Local Officials Who Don't Aid Immigration Enforcement

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 15th Circuit Considers Challenge to Louisiana's Ten Commandments Law

- 2Crocs Accused of Padding Revenue With Channel-Stuffing HEYDUDE Shoes

- 3E-discovery Practitioners Are Racing to Adapt to Social Media’s Evolving Landscape

- 4The Law Firm Disrupted: For Office Policies, Big Law Has Its Ear to the Market, Not to Trump

- 5FTC Finalizes Child Online Privacy Rule Updates, But Ferguson Eyes Further Changes

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250