Gorsuch and Kennedy Click in Online Sales Tax Case

In April, the two justices likely will align in the multibillion-dollar battle over state taxation of online retail sales.

March 07, 2018 at 02:47 PM

5 minute read

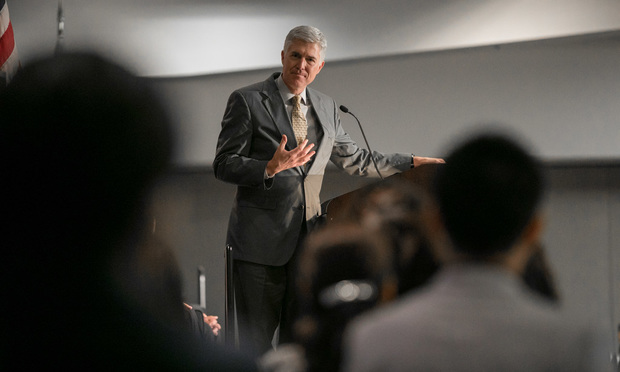

Justice Neil Gorsuch at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Conference in San Francisco. Credit: Jason Doiy/ ALM

Justice Neil Gorsuch at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Conference in San Francisco. Credit: Jason Doiy/ ALM Besides their Western backgrounds and their justice-former clerk connection, Anthony Kennedy and Neil Gorsuch seem to have little in common in style and views. But in April, the two justices likely will align in the multibillion-dollar battle over state taxation of online retail sales.

In South Dakota v. Wayfair, set for argument April 17, South Dakota urges the justices to invalidate a 51-year-old rule that a business must have a physical presence in a state before that state can require it to collect sales taxes.

The Supreme Court challenge is the second high-profile case this term in which the justices are being asked to overrule or cabin a long-standing precedent because it was allegedly incorrectly decided. The 1977 decision in the labor case Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, upholding the lawfulness of “fair share” fees imposed on non-union members, is also under attack.

The physical presence requirement for sales taxes, first established in a 1967 high court decision and reaffirmed 25 years later in Quill v. North Dakota, was wrong in 1992 and “far more wrong” today, South Dakota's lawyer, Eric Citron of Washington's Goldstein & Russell, said in a court brief. Citron continued: “Because, in the digital age where ubiquitous e-commerce is projected into our homes and smartphones over the internet, traditional 'physical' presence is an increasingly poor proxy for a company's 'nexus' with any given market or state.”

Justice Anthony Kennedy

Justice Anthony KennedyNot surprisingly, in the third paragraph of his brief's introduction, Citron has separate references to Kennedy and Gorsuch, both of whom had indicated at different times that the Quill decision was on life support.

South Dakota and other states have chafed under the physical presence requirement for a number of years, viewing that potential sales tax revenue as an aid particularly in lean budget times. But it was Kennedy's concurrence in the court's 2015 decision in Direct Marketing Association v. Brohl that galvanized states such as South Dakota, Colorado and Alabama to take steps, either in litigation or legislation, to challenge or circumvent the requirement.

In Brohl, Kennedy said the high court should have used the opportunity in Quill to reevaluate that 1967 decision establishing the physical presence requirement—National Bellas Hess v. Ill. Dept. of Revenue—as well as a more refined test that followed Bellas Hess in 1977.

Kennedy wrote:

“The Internet has caused far-reaching systemic and structural changes in the economy, and, indeed, in many other societal dimensions. Although online businesses may not have a physical presence in some states, the web has, in many ways, brought the average American closer to most major retailers…. Given these changes in technology and consumer sophistication, it is unwise to delay any longer a reconsideration of the court's holding in Quill. A case questionable even when decided, Quill now harms states to a degree far greater than could have been anticipated earlier…. The legal system should find an appropriate case for this court to reexamine Quill and Bellas Hess.”

The Brohl case turned on a jurisdictional issue and so it was sent back to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit for a ruling on the merits of Colorado's tax reporting requirements on out-of-state retailers. Gorsuch, then serving on the Tenth Circuit, was on the three-judge panel that subsequently upheld the state's law.

In a concurring opinion, Gorsuch in 2016 wrote that the Supreme Court decided Quill on the basis of stare decisis—to preserve its earlier decision in Bellas Hess and to protect the mail-order and internet vendors who had come to rely on it.

“Everyone before us acknowledges that Quill is among the most contentious of all dormant commerce clause cases,” he wrote. He called Quill an “oddity that, if anything, seems to grow by the day, for if it were ever thought that mail-order retailers were small businesses meriting (constitutionalized, no less) protection from behemoth brick-and-mortar enterprises, that thought must have evaporated long ago.”

Quill's very reasoning, he added, “seems deliberately designed to ensure that Bellas Hess's precedential island would never expand but would, if anything, wash away with the tides of time.”

The Trump administration's U.S. Justice Department this week filed an amicus brief supporting South Dakota. However, the government argues that Quill and Bellas Hess do not have to be overruled but should not be extended to e-commerce. Instead, those two precedents should be limited to “traditional mail-order retailers whose only connection to a State is by mail or common carrier,” wrote Solicitor General Noel Francisco.

Wayfair, Overstock.com and Newegg Inc., represented by George Isaacson of Brann & Isaacson in Lewiston, Maine, have not yet filed their response on the merits.

Read more:

'He's Not Bashful' Ted Olson Evaluates Neil Gorsuch's Silence in Union Fees Argument

5 Key Moments From Supreme Court's Union-Fee Arguments

Neil Gorsuch Dines With US Senators, and It's the Talk of This Town

Justice Ginsburg Scorns 'History Lesson' in This Gorsuch Dissent

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Weil, Loading Up on More Regulatory Talent, Adds SEC Asset Management Co-Chief

3 minute read

Wells Fargo and Bank of America Agree to Pay Combined $60 Million to Settle SEC Probe

Crypto Entrepreneur Claims Justice Department’s Software Crackdown Violates US Constitution

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Paul Hastings, Recruiting From Davis Polk, Continues Finance Practice Build

- 2Chancery: Common Stock Worthless in 'Jacobson v. Akademos' and Transaction Was Entirely Fair

- 3'We Neither Like Nor Dislike the Fifth Circuit'

- 4Local Boutique Expands Significantly, Hiring Litigator Who Won $63M Verdict Against City of Miami Commissioner

- 5Senior Associates' Billing Rates See The Biggest Jump

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.