When Scalia Died: New Documents Capture Confusing Day

Part of the problem surrounding Justice Antonin Scalia's death, the documents reveal, was that he chose not to have federal protection while at the Cibolo Creek Ranch, the hunting resort where he died in February 2016.

March 14, 2018 at 01:46 PM

4 minute read

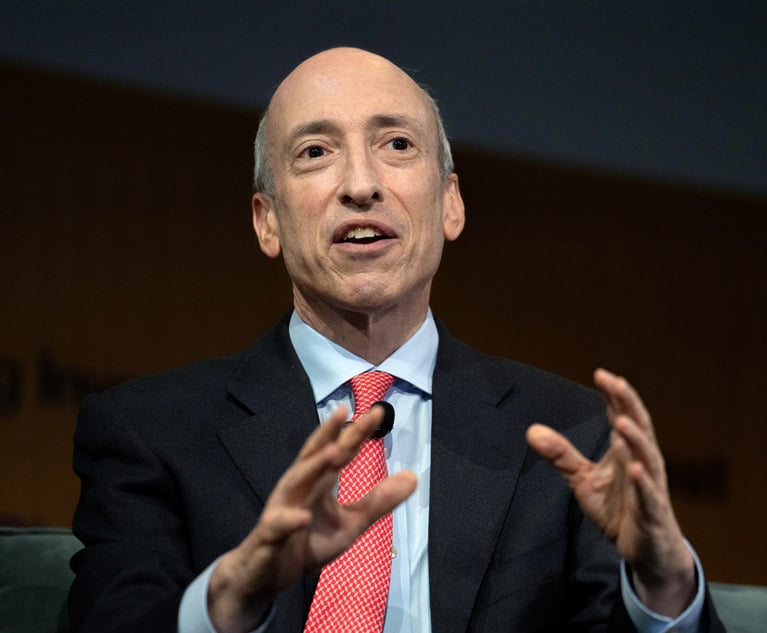

Justice Antonin Scalia, 1936-2016.

Justice Antonin Scalia, 1936-2016. Newly disclosed documents from the U.S. Marshals Service appear to show confusion and a lack of coordination after the death of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia in West Texas in February 2016.

“It was a weekend morning, and in a remote part of Texas, and it took several hours for the right people to be notified,” said Gabe Roth, executive director of Fix the Court, who sought and sued for the documents under the Freedom of Information Act.

By statute and according to policy directives included in the released documents, the Marshals Service is tasked with protecting justices during domestic travel outside the Washington area “when requested.”

Part of the problem surrounding Scalia's death, the documents reveal, was that Scalia chose not to have federal protection while at the Cibolo Creek Ranch, the hunting resort where he died.

Scalia only requested help from the marshal's service while changing planes in Houston from a Southwest Airlines flight to a private charter plane, where he joined six other unnamed people for the flight to the ranch, according to the documents.

The 380 pages of documents, many of them heavily redacted, fill in some details of Scalia's trip to Texas, which came just a few days after returning from a trip to Hong Kong and Singapore.

In a Feb. 9 email, an unnamed person at the court said “originally, we did not think he would need anything from the marshals” for the Texas trip. But the email went on to ask for protection during Scalia's flight transfer and layover in Houston. The email added, “He will be traveling with a gun.”

The documents also include a detailed timeline of the Saturday morning when Scalia was found dead in his room at 11 a.m. at the ranch by a housekeeper. Soon after, an unnamed person tried to reach federal authorities, “with no response.” Apparently, that first message said someone in Scalia's party had died, not Scalia himself.

At 12:41 p.m., the local sheriff notified the nearest marshal's service office, and word began to spread within federal law enforcement agencies, including the Supreme Court police. At 2:38 p.m., the first of many officers from the marshal's service arrived at the ranch. At 10 p.m., they took inventory of Scalia's effects in the room and ultimately put them in a marshal's service safe.

One email exchange seems to reflect concern that the Marshals Service would get in trouble for not being with Scalia at the ranch.

A Feb. 14 Washington Post article circulated to officials included a statement from the service stating that Scalia had declined protection and that deputy U.S. marshals from West Texas “responded immediately upon notification of Justice Scalia's passing.” One official of the service said the statement was “relatively good,” adding “Let's hope it doesn't grow legs.”

“The public should be confident that Supreme Court justices are well-protected, both inside their building and when they venture out into the world,” Roth said. “That the justices can decline protection when they travel to the most far-flung places in the country does not seem appropriate, given the expansive reach and resources of the U.S. Marshals Service, and the fact that so many justices choose to remain on the bench well into old age.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllShaq Signs $11 Million Settlement to Resolve Astrals Investor Claims

5 minute read

Am Law 100 Partners on Trump’s Short List to Replace Gensler as SEC Chair

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1I’m A Lawyer, What Can I Sell?

- 2Internal GC Hires Rebounded in '24, but Companies Still Drawn to Outside Candidates

- 3How I Made Office Managing Partner: 'Don’t Be an Opportunity Killer,' Says Thomas Haskins of Barnes & Thornburg

- 4People in the News—Feb. 7, 2025—Gawthrop Greenwood, Lamb McErlane

- 5NY No-Fault Insurance Adopts Worker’s Compensation Fee Schedule

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250