Emails, PowerPoints and YouTube TV: Judge in AT&T Trial Mulls Evidence

Lawyers for AT&T have filed hundreds of objections to the government's proposed evidence in its case against the telecom giant's merger with Time Warner.

March 19, 2018 at 03:24 PM

7 minute read

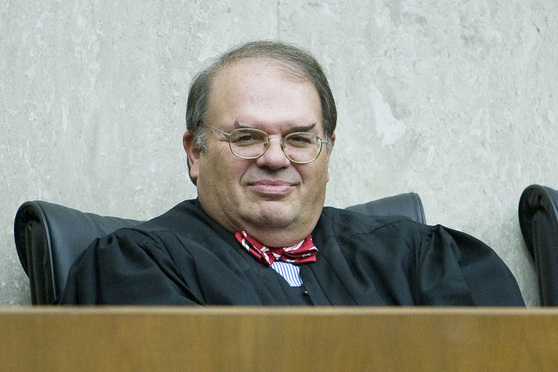

On the opening day of what is likely to be the most consequential antitrust showdown in decades, a federal judge contemplated how to evaluate whether tools of the modern workplace, like email chains, can be used as evidence against AT&T.

District Judge Richard Leon of the District of Columbia, who is overseeing the Justice Department's lawsuit against AT&T's proposed merger with Time Warner, said in Monday's evidentiary hearing that there were a couple of overarching issues in AT&T's objections to the government's evidence, including many focused on relevancy. But one was also whether certain types of evidence, such as emails, counted as business records exempt from court rules against hearsay evidence.

Opening arguments in the case are expected to begin Wednesday. The Justice Department sued AT&T in November, alleging the proposed $85 billion acquisition of Time Warner would increase prices for, and therefore harm, consumers. AT&T argues the merger will increase efficiencies and keep the company competitive amid a changing media landscape it says companies like Netflix and Amazon are taking over.

On Monday, Leon expressed concern about whether certain emails from lower-level company employees could qualify for the business record exemption to the hearsay rule by virtue of being prepared on a business computer and sent from a business email. Leon said it would likely be a “recurring issue.”

O'Melveny & Myers partner Daniel Petrocelli, who represents AT&T, told the judge the government has more than 100 exhibits “replete” with emails and PowerPoint slides, many of which should only be admitted if a witness can attest to their contents and put them in context.

Government lawyer Eric Welsh said that only a small group of the documents the government proposed to enter into the record did not have a corresponding witness to discuss them. Welsh told the judge, who remarked on the large number of PowerPoint slides the government wanted to show, that such slides are a modern day version of memoranda and were necessary to show how business was being done.

Leon said he would need to “peel back the artichoke” to understand who authored the slides, who ordered that they be created and how they were used. He said the stakes in this case were too high to just admit all the slides in one fell swoop. Welsh said the government believed there was authority for admission of the documents and would gladly provide further briefing.

Petrocelli said the discussion showed that there “isn't a one-shoe-fits-all answer” to the issue, and, later, added that it was always the “providence of the trial judge” to decide what evidence is admissible. He said a “document dump” is typically disfavored by courts.

AT&T also objected to the use of an October 2017 presentation by Google, titled “YouTube TV,” the judge said. Welsh, who noted the exhibit was confidential so he couldn't say much about it, said a Google employee had been deposed to talk about the presentation.

He said it was highly relevant to how Google, an AT&T competitor, viewed the importance of Turner content. A main facet of the government's argument is that Turner video content, which includes HBO programming, is “must have” TV, meaning AT&T is likely to raise fees for other providers who want to show it.

Petrocelli said AT&T objected to the use of the presentation because it was irrelevant, but the principal objection is that it's also hearsay. Leon said he would need to hear from the witness before he would admit the presentation as evidence. He said he could “tell already” it was something he would have questions about.

There was also some discussion of whether AT&T subsidiary DirecTV should be named as a defendant in the case, as the government has done, and what statements made by DirecTV prior to AT&T's 2015 acquisition of the company could be admitted into the record. That included comments DirecTV made to regulators about the 2011 merger of NBCUniversal and Comcast.

Petrocelli said DirecTV, as a subsidiary, should not even be a party to a case and that comments it made before it was joined with AT&T should not be considered. Welsh, however, said the comments went to the central issues of the case at hand.

Leon said he was not inclined to allow the exhibit into the record except for use against DirecTV. The government also wanted to enter seven expert reports from other antitrust cases and regulatory matters. Leon also said that, to AT&T's favor, he likely would not allow the reports.

The evidentiary proceedings are expected to last through the end of the day Monday and potentially into Tuesday.

The last portion of Monday's hearing focused on issues surrounding confidentiality. Welsh said some third parties are concerned about confidential information being made public through their testimony or documents, which is why the government earlier requested that Leon issue a protective order allowing the courtroom to be sealed for some witnesses to testify privately.

Welsh added AT&T also designated many of its own documents as confidential, which will make it difficult to examine witnesses effectively. He said AT&T appeared to designate some specific statement that would likely help the government's case as confidential.

Petrocelli said AT&T only wants the same level of confidentiality that applied to third parties' documents.

“It has to be the same, your honor,” Petrocelli told the judge. “We're not asking for special treatment.”

The judge said it will be key to know whether third parties' confidential details, such as financial records or other data, are necessary to support the conclusion by third-party witnesses that the merger would result in increased prices or that Time Warner would withhold certain content.

“Or, is that prognostication really based on instinct?” Leon asked.

The judge, who has significant experience with national security cases, said the confidentiality issue is nothing new but that it can be a “painstaking process” to go back and forth over the designation.

He told the parties to discuss the issues further and be prepared to address them Tuesday.

Then, a third-party lawyer for Sony International, John Cove of Shearman & Sterling, approached the bench to address the judge. Leon asked his name, then stopped him from saying anything further. After some brief crosstalk, the judge admonished Cove, pointing out that he had never been in Leon's courtroom before, and that the court reporter could not do his job if they were both speaking at the same time.

“Sir, when I talk, you stop,” Leon told the lawyer. He said that Shearman & Sterling had many lawyers, and if Cove could not attend tomorrow, he could ask someone to come in his place.

Leon then promptly ended the hearing.

Read more:

AT&T Trial Counsel Petrocelli Is No Antitrust Expert—But That May Be a Plus

It's Showtime: What to Watch at AT&T-Time Warner Antitrust Trial

Akin Gump Involved in Korean Corruption Scandal Implicating Former President Lee

$33M SEC Whistleblower Award Sets Agency Record

First Fatal Accident Involving Autonomous Uber Car Raises Novel Legal Issues

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

3 minute read

Private Equity Giant KKR Refiles SDNY Countersuit in DOJ Premerger Filing Row

3 minute read

Three Akin Sports Lawyers Jump to Employment Firm Littler Mendelson

Trending Stories

- 1‘The Decision Will Help Others’: NJ Supreme Court Reverses Appellate Div. in OPRA Claim Over Body-Worn Camera Footage

- 2MoFo Associate Sees a Familiar Face During Her First Appellate Argument: Justice Breyer

- 3Antitrust in Trump 2.0: Expect Gap Filling from State Attorneys General

- 4People in the News—Jan. 22, 2025—Knox McLaughlin, Saxton & Stump

- 5How I Made Office Managing Partner: 'Be Open to Opportunities, Ready to Seize Them When They Arise,' Says Lara Shortz of Michelman & Robinson

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250