Why Some Judicial Nominees Struggle When Asked About 'Brown v. Board of Education'

For some nominees, the concern is that by answering explicitly, they would be viewed as biased. For others, the decisions they are being asked to embrace are too controversial to touch.

April 12, 2018 at 03:17 PM

4 minute read

U.S. Supreme Court. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

U.S. Supreme Court. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM Judicial nominee Wendy Vitter fell into a well-trodden trap on Wednesday when a U.S. senator asked if she believed that the landmark desegregation ruling Brown v. Board of Education was correctly decided.

“I don't mean to be coy,” said Vitter, nominated by President Donald Trump for a seat on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana. “But I think I can get into a difficult, difficult area when I start commenting on Supreme Court decisions—which are correctly decided and which I may disagree with.”

She added that the ruling “is Supreme Court precedent. It is binding. If I were honored to be confirmed, I would be bound by it and of course I would uphold it.” But the damage was done, and civil rights groups were unforgiving:

WATCH: During her confirmation hearing this morning (yes, this morning – in 2018), judicial nominee Wendy Vitter refused to say whether she agreed with the result in Brown v. Board of Education. #UnfitToJudge pic.twitter.com/RWroh0XUIC

— The Leadership Conference (@civilrightsorg) April 11, 2018

Vitter, general counsel to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans, is not the only judicial nominee to draw criticism when asked about Brown and other landmark decisions. For some nominees, the concern is that by answering explicitly, they would be viewed as biased if a case challenging the precedent came before them—even when that is highly unlikely.

In 1986, the late Justice Antonin Scalia went so far as to say during his confirmation hearing, “I do not think I should answer questions regarding any specific Supreme Court opinion, even one as fundamental as Marbury v. Madison.”

For others, the decisions they are being asked to embrace are too controversial to touch. Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling declaring the right to abortions, is one such decision, especially because abortion-related litigation and legislation persists. Brown is also criticized by some who argue that it does not square with the original meaning of the Constitution.

At a Senate hearing last month, Sixth Circuit nominee John Nalbandian agreed Brown was correctly decided, according to the Vetting Room blog. But when asked moments later about Roe, Nalbandian changed his tune: “I'm reluctant, and I think it would be inappropriate for me to go down a list of Supreme Court cases and say I think this case was rightly decided and that case was not, because I think it would call into question my partiality going forward.”

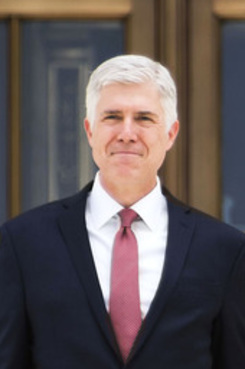

Justice Neil Gorsuch. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi

Justice Neil Gorsuch. Credit: Diego M. RadzinschiSen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Connecticut, who pressed Vitter about Brown, repeatedly asked Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch about Brown during his confirmation hearing last year.

Twice, Gorsuch repeated his reply that Brown was “a correct application of the law of precedent.”

A frustrated Blumenthal reminded Gorsuch that Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. in 2005 had told Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Massachusetts, “I do” when asked if he agreed with Brown.

“There's no daylight here,” Gorsuch answered, intimating—but not quite saying outright—that he was OK with the Brown decision.

The late conservative Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork also said he agreed with Brown during his unsuccessful 1987 confirmation hearing, according to Michael Gerhardt, professor at University of North Carolina School of Law, who has advised senators including Blumenthal on confirmation hearings.

Gerhardt said that asking nominees about Brown is a legitimate question for discerning “whether there is any space between the nominee as a person and as a judge” when it comes to the issue of race.

Read more:

Trump Picks Judges 'He Can Relate To,' McGahn Tells CPAC

Covington, McGuireWoods Partners Among New Slate of Judicial Nominees

Report: Trump's Judicial Nominees Have Most 'No' Votes So Far

Meet Matthew Petersen, DC Court Nom Who Flunked Senator's Pop Quiz

Federal Judicial Nominee Flunks 'Motion in Limine' Definition at Senate Hearing

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Something Else Is Coming': DOGE Established, but With Limited Scope

Supreme Court Considers Reviving Lawsuit Over Fatal Traffic Stop Shooting

US DOJ Threatens to Prosecute Local Officials Who Don't Aid Immigration Enforcement

3 minute read

US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250