Plaintiffs Lawyers in Flint Water Litigation Escalate Fight Over Fees, Clients

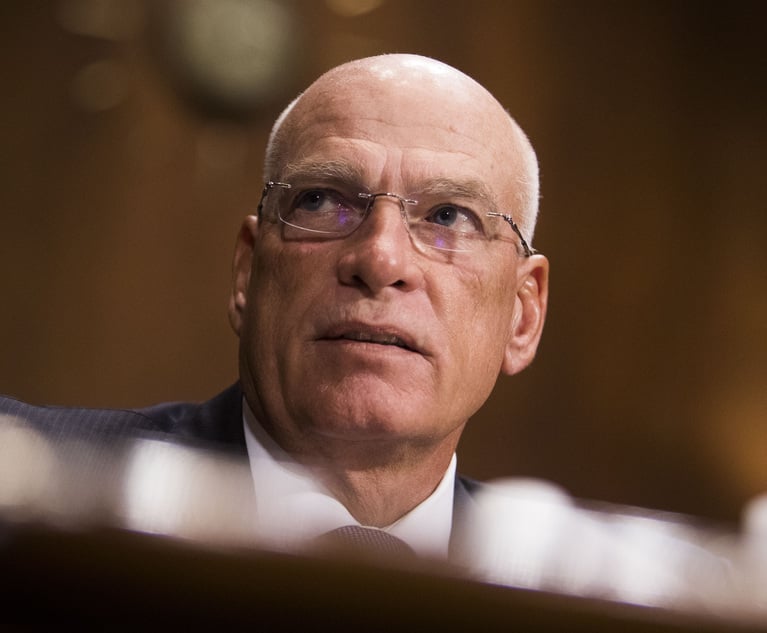

Ted Leopold and Michael Pitt, co-lead counsel for the lead class action brought on behalf of Flint residents, have asked U.S. District Judge Judith Levy, who is based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, to remove Hunter Shkolnik as one of two lawyers serving as liaison counsel to the individual cases.

May 01, 2018 at 06:51 PM

7 minute read

The leadership fight in the Flint water contamination cases has escalated, with co-lead counsel firing back against “false and misleading accusations” and at least one defendant in the case raising concerns about the communications that all the lead plaintiffs lawyers have had with prospective class members.

Ted Leopold and Michael Pitt, co-lead counsel for the lead class action brought on behalf of Flint residents, have asked U.S. District Judge Judith Levy, who is based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, to remove Hunter Shkolnik as one of two lawyers serving as liaison counsel to the individual cases. They claimed Shkolnik was luring prospective class members into signing excessive and illegal retainer agreements with his firm, New York-based Napoli Shkolnik.

Shkolnik called the removal request a “blatant money grab” over fees that in his view was touched off when he refused to accept Leopold and Pitt's demands that he stop soliciting clients while they got 80 percent of all common benefit fees. He then asked Levy, of the Eastern District of Michigan federal court, to remove Leopold and Pitt as co-lead counsel.

On Monday, Leopold, of Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, and Pitt, of Pitt McGehee Palmer and Rivers in Royal Oak, Michigan, fired back, calling Shkolnik's “baseless accusations of unethical conduct” a “red herring.”

“Co-lead counsel's motion raises serious ethical concerns about Mr. Shkolnik's conduct,” they wrote. “Through these actions, Mr. Shkolnik has fundamentally damaged the trust that co-lead counsel previously placed in him in supporting his appointment as co-liaison counsel and has raised serious questions about his ability and willingness to cooperate with co-lead counsel in pursuing these actions for the common benefit of the residents of Flint.”

The dispute, they wrote, has “nothing to do with competing for fees or clients.” But they added that Shkolnik started that dispute by demanding that he and his fellow co-liaison counsel, Corey Stern, get 40 percent of a potential common benefit fund, plus their contingency fees.

In a separate declaration, Stern, of Levy & Konigsberg, called on both sides to reach a truce for the sake of the Flint litigation.

“I consider both sets of allegations to be serious and I recognize the magnitude of what each side is seeking,” he wrote in a Monday filing. “I am genuinely troubled by the dispute that has arisen between these attorneys and the allegations underlying it.”

Despite the “plethora of alleged violations and conflicts,” however, he didn't want any of the lawyers removed from their leadership posts.

“Despite their different approaches to this litigation, they are in their own right talented attorneys, and I have witnessed each of them dedicating substantial energy advocating for the people of Flint, oftentimes together,” he wrote.

Also wading into the debate was one of the three engineering defendants, Veolia North America. Its attorneys wrote in a response on Monday that documents Shkolnik submitted last month “warrant further inquiry.” Further, all three lawyers “may have taken advantage of their positions to engage in inaccurate or otherwise misleading communications to members of the Flint community,” wrote James Campbell, president of Campbell, Campbell, Edwards & Conroy in Boston, and Cheryl Bush, founding partner of Bush, Seyferth & Paige in Troy, Michigan.

The lawsuits, many of which have been consolidated, target engineering firms and more than a dozen government officials over the 2014 decision to temporarily shift the city's water supply from Lake Huron to the Flint River. The change was made despite studies warning that the corrosive nature of the river water could risk leaching lead from old pipes into Flint's drinking water supply.

Last summer, Levy appointed Pitt and Leopold as lead counsel for all the class actions in federal court, and Shkolnik and Stern as co-liaison for hundreds of individual cases, most of which involve medical claims. The lawyers have filed separate complaints, but many of their claims have overlapped.

Leopold and Pitt claimed that Shkolnik's retainer agreements violated the Michigan Rules of Professional Conduct and that, even after changing them, he continues to advertise on his firm's website that Flint residents need to retain lawyers soon, despite no such deadline in place.

“It is important that the residents of Flint have accurate and truthful information about this litigation,” they wrote.

They also never insisted that Shkolnik stop signing up clients—only that he make sure to advise them of their right to remain in the class action—and never demanded a percentage of the common benefit fund.

In fact, they wrote, Shkolnik first raised the idea of a common benefit fund in January when he insisted that each member of the leadership team get 20 percent. That meant that he and Stern would get 40 percent “even though they have been appointed as liaison counsel for the individual cases and are not serving as class counsel.”

In an interview, Shkolnik stood by his original claim.

“It's class counsel that was more concerned about fees than anything else, and now they're trying to back out,” he said. “We intend to file a reply brief, and we will point out the fact that class counsel, through emails and exhibits attached to our motion, are seeking fees and not resolution of the case.”

In Monday's response, Veolia's lawyers criticized both sides. Leopold and Pitt set up a website that was “replete with language implying that putative class members are parties to this litigation” and that co-lead counsel's legal team represents them, they wrote.

“Communications such as these suggest that members of the Flint community already are represented in this litigation, thus potentially deterring them from seeking advice from their own lawyers in order to understand how best to protect their own interest,” they wrote.

And Shkolnik's statements at a town hall meeting on Feb. 18 in Flint appeared to mislead residents about how class actions work, they wrote.

“Co-liaison counsel's 'town hall' statements could suggest that the role of co-liaison counsel is to personally represent each individual plaintiffs who chooses not to take part in a class action,” they wrote. “They describe the settlement as something that is forthcoming. And they suggest that co-liaison counsel are the only actors who are offering the truth.”

Stern said he would support whatever actions Levy took to get to the “crux of this quarrel.” But he called on both sides to move forward.

“The attorneys that have the opportunity to prosecute and defend these cases are in a small way helping write chapters in the history of an American city, and possibly of something much larger,” Stern wrote. “We owe it to our clients in the litigation as a whole, and to our profession, to undertake our roles in ways that honor this process and the people it affects most. I have seen these lawyers do that together and individually at various times throughout this litigation.”

➤➤ Get more class action news and commentary straight to your in-box with Critical Mass by Amanda Bronstad. Learn more and sign up here.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Federal Judge Sets 2026 Admiralty Bench Trial in Baltimore Bridge Collapse Litigation

3 minute read

'Appropriate Relief'?: Google Offers Remedy Concessions in DOJ Antitrust Fight

4 minute read

'Serious Disruptions'?: Federal Courts Brace for Government Shutdown Threat

3 minute read

'Unlawful Release'?: Judge Grants Preliminary Injunction in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1It's Time To Limit Non-Competes

- 2Jimmy Carter’s 1974 Law Day Speech: A Call for Lawyers to Do the Public Good

- 3Second Circuit Upholds $5M Judgment Against Trump in E. Jean Carroll Case

- 4Clifford Chance Hikes Partner Pay as UK Firms Fight to Stay Competitive on Compensation

- 5Judicial Conduct Watchdog Opposes Supreme Court Justice's Bid to Withdraw Appeal of Her Removal

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250