Baltimore State's Attorney Mosby Can't Be Sued by Cops in Freddie Gray Death Prosecution, Circuit Rules

"We soundly reject the invitation to cast aside decades of Supreme Court and circuit precedent to narrow the immunity prosecutors enjoy," wrote Fourth Circuit Chief Judge Roger Gregory. "And we find no justification for denying Mosby the protection from suit that the Maryland legislature has granted her."

May 08, 2018 at 03:11 PM

4 minute read

A federal appeals court has ruled that Baltimore State's Attorney Marilyn Mosby cannot be sued for her comments and actions following the death of Freddie Gray Jr., whose death while in the custody of city police led to public demonstrations, riots and officer prosecutions.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruled on Monday that Mosby was protected by absolute prosecutorial immunity, even though the officers charged in connection with Gray's death ultimately weren't convicted.

In the ruling, the Richmond, Virginia-based appeals court overturned a decision by U.S. District Judge Marvin Garbis of the District of Maryland, who allowed counts of defamation, malicious prosecution and false-light invasion of privacy to move forward, denying Mosby's motion for dismissal.

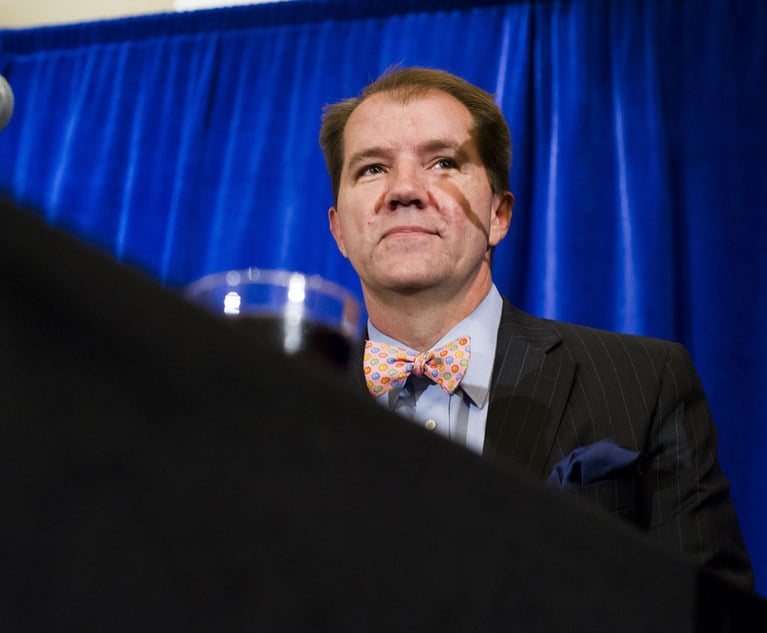

“We soundly reject the invitation to cast aside decades of Supreme Court and circuit precedent to narrow the immunity prosecutors enjoy,” wrote Chief Judge Roger Gregory for the court. “And we find no justification for denying Mosby the protection from suit that the Maryland legislature has granted her.”

“A young African-American man had been killed in the custody of the Baltimore City Police Department, and the city was rioting,” Gregory said. “Pursuing justice—i.e., using the legal system to reach a fair and just resolution in Gray's death—was not a political move. It was Mosby's duty,” Gregory added.

Circuit Judges J. Harvie Wilkinson and Pamela Harris joined in the reversal, though Wilkinson did issue a concurring opinion.

Gray, 25, suffered a severe spinal injury while in police custody on April 12, 2015, and died a week later. Six officers involved in his arrest and transport were charged with criminal counts, including manslaughter and second-degree murder. Of the six, one proceeded to a trial that ended in a hung jury, leading to a mistrial, and two others were acquitted by a judge of all charges. Mosby then dropped the remaining cases.

Five of the officers—Lt. Brian Rice and Sgt. Alicia White, and Officers Edward Nero, Garrett Miller and William Porter—filed a civil suit for what they said was a malicious prosecution. Their lawyers claimed Mosby didn't have enough evidence and charged them to ease the unrest in Baltimore that followed Gray's death.

Gray's death led to rioting in the city, and eventually Maryland's governor called in the National Guard and state police to respond.

Following the acquittals of the officers, the U.S. Department of Justice declined to pursue separate civil rights violations charges.

After the appeals court ruling Monday, Mosby issued a statement. “I support the court's opinion that the people of Baltimore elected me to deliver one standard of justice for all, and that using the legal system to reach a fair and just resolution to Gray's death was not a political move, but rather it was my duty.”

The officers were represented by Joseph Mallon Jr. of Mallon & McCool in Baltimore; Reisterstown, Maryland, solo David Ellin; and Baltimore solo Michael Glass. Mallon and Glass did not return telephone calls.

Ellin said, in an email, “We feel confident the Supreme Court will hear this matter and when they do, we'll have at least five justices on our side.”

One of the major accusations against Mosby was that she misused the power of her office in statements she made to the public in the days following Gray's death.

“I will seek justice on your behalf,” she told city residents during a press conference. “[O]ur time is now.”

The police officers said Mosby made those statements in her own personal interest.

The appeals court disagreed with Garbis' ruling that the officers' lawsuit could move forward, and called the officers' arguments “entirely devoid of support.”

There was “no reasonable inference that Mosby acted for reasons other than furthering the operations of the State's Attorney's Office,” Gregory said. “The people of Baltimore elected Mosby to deliver justice.”

He added, “Perhaps to the officers' chagrin, they must accept that they are subject to the same laws as every other defendant who has been prosecuted and acquitted.”

In his concurring opinion, Wilkinson wrote that, if the officers wanted to pursue complaints against Mosby, they should have done so through Maryland's attorney ethics system, and not through “private tort suits.”

“Baltimore's citizens had their faith shaken, not only in the police, but in the very ability to administer justice,” he said. “Mosby responded to a crisis.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'New Circumstances': Winston & Strawn Seek Expedited Relief in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute read

5th Circuit Rules Open-Source Code Is Not Property in Tornado Cash Appeal

5 minute read

DOJ Asks 5th Circuit to Publish Opinion Upholding Gun Ban for Felon

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250