SG Urges SCOTUS to Review 'Clear Evidence' Ruling in Fosamax Case

The U.S. solicitor general has asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review a case that addresses one of the most significant federal pre-emption issues for brand drug companies since Wyeth v. Levine.

May 24, 2018 at 07:34 PM

5 minute read

Fosamax

Fosamax

The U.S. solicitor general has asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review a case that addresses one of the most significant federal pre-emption issues for brand drug companies since Wyeth v. Levine.

In a brief filed on Tuesday, Principal Deputy Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall urged the high court to take up a petition filed by Merck & Co. asking to reverse the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit's reinstatement of more than 500 cases brought over osteoporosis drug Fosamax. At issue is the Supreme Court's “clear evidence” holding in its 2009 decision in Wyeth and who—a jury or a judge—should decide whether the U.S. Food and Drug Administration would have rejected a drug manufacturer's proposed labeling changes.

“The underlying issue—whether the meaning and effect of an FDA labeling decision present a question of law for courts to resolve or a question of fact for lay juries to determine—is significant. The petition clearly presents that issue in a context in which hundreds of separate cases asserting similar failure-to-warn claims turn on its proper resolution,” Wall wrote. “Although the question is close, the government concludes that, on balance, review is warranted at this time.”

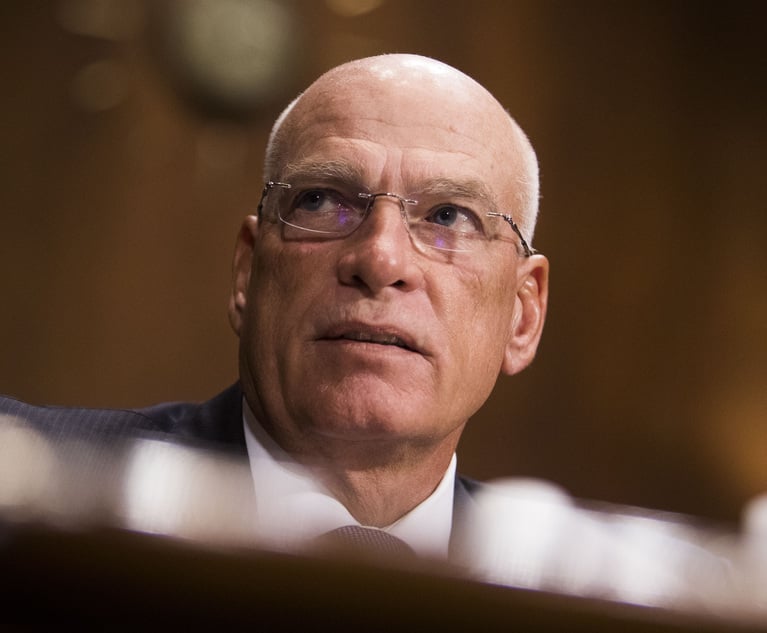

Solicitor General Noel Francisco, who was chairman of the government regulation practice at Jones Day before joining the Trump administration last year, recused himself from the case. Jones Day's Shay Dvoretzky, a partner in Washington, filed Merck's petition on Aug. 22.

The government's involvement could persuade the Supreme Court to take up the case, according to Reed Smith's James Beck, author of the Drug & Device Law blog.

“The mere fact that the SG was asked to comment means this case is being seriously considered by the court,” he wrote in an email. “The SG's opinion, and the strong brief backing it up, certainly makes it more likely, still, that the court will grant the appeal—but the question remains 'close,' as the SG stated, so it's still wait and see.”

In Wyeth, the Supreme Court held that the FDA's approval of labeling changes on a drug did not necessarily grant federal pre-emption in failure-to-warn cases because drug manufacturers bore responsibility for labeling changes to their products. Drug manufacturers could assert such a defense, however, when there was “clear evidence” that the regulatory agency would not have approved such a change.

Courts have grappled with how to interpret “clear evidence” and, according to Merck, many have tilted the scales toward the plaintiffs—with the Fosamax case an “extreme illustration.”

“Left to their devices, the courts have made proving impossibility pre-emption under Levine next to impossible,” Dvoretzky wrote in Merck's petition. “The Third Circuit's decision below epitomizes that shift, rendering the defense truly academic.”

Three amicus groups—the Product Liability Advisory Council, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce—filed amicus briefs supporting Merck's petition.

In 2014, U.S. District Judge Joel Pisano in New Jersey granted summary judgment to Merck on its federal pre-emption defense. But the Third Circuit found that Merck had not proven there was “clear evidence” that the FDA would have rejected changes to Fosamax's labels warning of its link to femur fractures. Merck had argued that the FDA's 2009 rejection of its proposed changes to the drug's label showed “clear evidence.” The panel insisted that there was no evidence that the FDA, which ended up ordering label changes to Fosamax in 2010, rejected the science behind the warning—rather than simply the wording. It also found that a jury, not a judge, should make the “clear evidence” determination.

Merck's petition said both findings were wrong.

But there is no circuit split—a point that both Merck, the government and plaintiffs attorney David Frederick brought up in their briefs. Frederick, a partner at Kellogg, Hansen, Todd Figel & Frederick, successfully argued for the plaintiffs in Wyeth v. Levine and in another case in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit sidestepped the “clear evidence” issue on Dec. 6 in reinstating 750 cases involving four diabetes drugs.

In the plaintiffs brief, Frederick wrote the Fosamax case also isn't a good test case because Merck's proposed labeling changes mentioned stress fractures, not femur fractures.

Wall, who filed the government's brief at the urging of the Supreme Court, acknowledged the courts might “refine the issue for review” but found Fosamax worthy of taking up because it dealt with an actual FDA labeling change—not a hypothetical one like in Wyeth.

“The legal question, although narrow in the context of this case involving an FDA decision rejecting a proposed labeling change, is important and cleanly presented,” he wrote. “Its practical implications are starkly illustrated by the volume of tort claims asserted against petitioner in this case. And the court's consideration of the proper method for resolving the pre-emption issue in this case may inform the proper analytical framework for resolving FDA pre-emption issues in light of Wyeth more generally.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Unlawful Release'?: Judge Grants Preliminary Injunction in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute read

Federal Judge Grants FTC Motion Blocking Proposed Kroger-Albertsons Merger

3 minute read

Frozen-Potato Producers Face Profiteering Allegations in Surge of Antitrust Class Actions

3 minute read

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250