Federal Circuit Won't Budge From Decision Reining in 'Alice'

Only one judge dissented from denial of en banc review in Berkheimer v. HP, though two others called on Congress or the Supreme Court to intervene.

May 31, 2018 at 06:27 PM

5 minute read

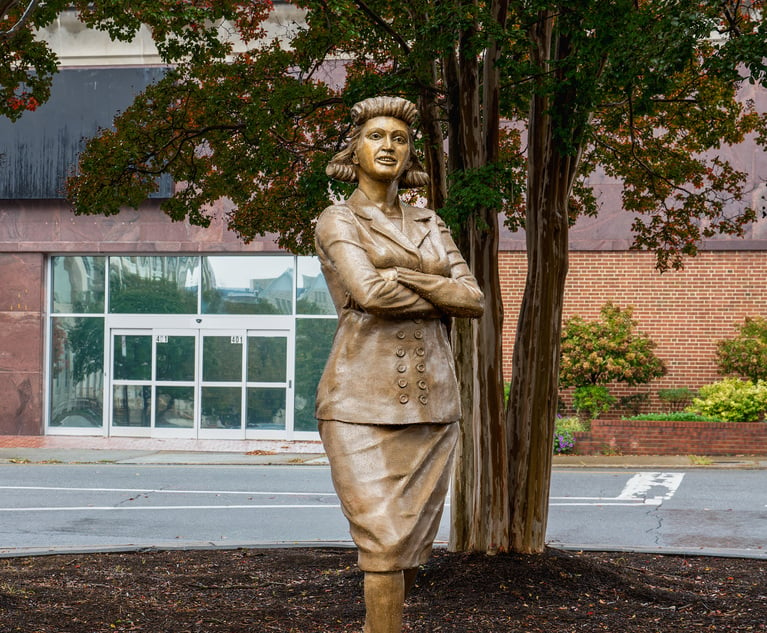

Judge Kimberly Ann Moore of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. (Courtesy photo)

Judge Kimberly Ann Moore of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. (Courtesy photo)

The U.S. Supreme Court's Alice opinion on patent eligibility got a formal haircut Thursday.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit announced that it's sticking with two February decisions that limit the kinds of patent cases that can be decided early in litigation on a Section 101 motion.

Only one of the court's 12 active judges dissented from the denial of en banc review in Berkheimer v. HP and Aatrix Software v. Green Shades Software, though two others also called on Congress or the Supreme Court to intervene.

“Section 101 issues certainly require attention beyond the power of this court,” Judge Alan Lourie wrote in a concurrence to the denial of en banc review.

➤➤ Keep up with the news that matters most to your practice. Follow Patent Litigation

The Supreme Court's 2014 Alice decision instructed courts to determine whether a patent claims abstract ideas, laws of nature or natural phenomena. If the answer is yes, and the claims can be implemented using well-understood, routine and conventional tools, then they lack an “inventive concept” and are ineligible for patent protection.

Though often criticized as an “I know it when I see it” test, Alice led to a sea change in district court patent litigation. Judges have frequently used the test to eliminate dubious patent claims on the pleadings or summary judgment. That cut down litigation costs, which in turn removed much of patent owners' settlement leverage.

But Judge Kimberly Moore's opinions in Berkheimer and Aatrix held that some subset of those cases should not be decided by judges as a matter of law. “Whether something is well-understood, routine, and conventional to a skilled artisan at the time of the patent is a factual determination,” she wrote in Berkheimer. And, sometimes, fact issues require trials to resolve.

The accused infringers in Berkheimer and Aatrix, backed by technology industry interest groups, implored the court to reconsider en banc. But only Judge Jimmie Reyna, who had dissented from the panel opinion in Aatrix, heard their call.

“The consequences of this decision are staggering and wholly unmoored from our precedent,” Reyna wrote. Refusal to go en banc “almost guarantees that Section 101 will rarely be resolved early in the case, and will instead be carried through to trial.”

But Moore got the support of four other Federal Circuit judges in sticking with Berkheimer. “Though we are a court of special jurisdiction, we are not free to create specialized rules for patent law that contradict well-established, general legal principles,” she wrote. Judges Timothy Dyk, Kathleen O'Malley, Richard Taranto and Kara Stoll joined Moore's concurrence from the denial of en banc review.

In his own concurrence, Lourie said the Federal Circuit is “bound to follow the script that the Supreme Court has written for us in Section 101 cases.” But he made clear he believes the high court began losing its way on Section 101 about six years ago with Prometheus v. Mayo, when it introduced the two-step “inventive concept” test.

“Even if [Berkheimer] was decided wrongly, which I doubt, it would not work us out of the current Section 101 dilemma. In fact, it digs the hole deeper by further complicating the Section 101 analysis,” Lourie wrote. “Resolution of patent-eligibility issues requires higher intervention, hopefully with ideas reflective of the best thinking that can be brought to bear on the subject.”

Judge Pauline Newman joined Lourie's concurrence.

The question now is how many Section 101 motions that otherwise would have been decided on the pleadings or summary judgment get pushed forward to trial, which would shift leverage back to the patent owner side.

Reyna pointed out that within just a few weeks of Berkheimer's issuance, a district judge in Los Angeles relied on the case to reject a Section 101 motion.

But some defense-side lawyers weren't too concerned. Winston & Strawn partner Katherine Vidal recently won a Federal Circuit appeal for SAP America Inc. that found no triable issues even under Berkheimer, because all of the patent claims were in the realm of abstract ideas with nothing else plausibly inventive. “I think the SAP pattern is the norm,” Vidal said Thursday.

Moore pointed to SAP and four other recent Federal Circuit decisions as evidence that the sky isn't falling on accused infringers. ”Our decisions in Berkheimer and Aatrix are narrow,” she wrote.

Weil, Gotshal & Manges partner Edward Reines said Berkheimer probably won't prevent accused infringers from getting rid of most straightforward business method or generic software claims. But as Section 101 motions target more technically complex patents outside of e-commerce, they might collide with Berkheimer more often.

Reines and other patent lawyers were abuzz about Lourie's critique of the Supreme Court's Section 101 caselaw. “Judge Lourie's speaking truth to power was the most interesting part” of the en banc order, Reines said.

Multiple bar associations have proposed model legislation for clarifying Section 101, and several senators peppered USPTO Director Andrei Iancu with questions about it at an oversight hearing earlier this month. Still, it's not clear that sufficient momentum exists in Congress for tackling the issue.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Irreparable Harm'?: US Judge Denies Big Pharma Motion to Halt FDA-Approved Generic Drug

3 minute read

'Johns Hopkins Preyed on Black Women': Ben Crump Reps Henrietta Lacks Estate

3 minute read

Several Am Law 100 Firms Help Compliance Startup SingleFile Raise $6.5M

Jenner, Looking at 'Stretch' Goals, Reached Double-Digit Revenue and Profit Growth

5 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250