Reading the Tea Leaves in 'Masterpiece Cakeshop'

In a term fraught with consequential cases, Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission brought the culture wars back to the justices' doorstep.

June 29, 2018 at 11:30 AM

7 minute read

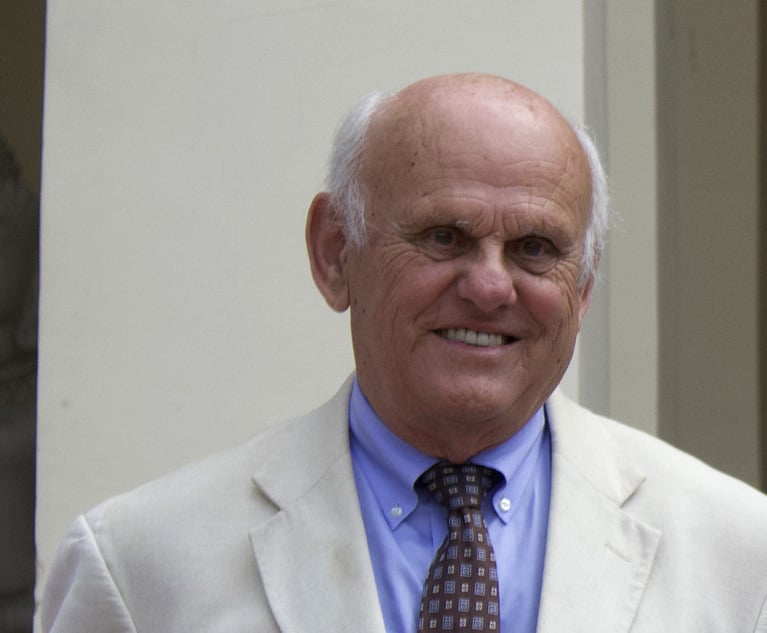

In this March 10, 2014, file photo, Masterpiece Cakeshop owner Jack Phillips decorates a cake inside his store in Lakewood, Colo.

In this March 10, 2014, file photo, Masterpiece Cakeshop owner Jack Phillips decorates a cake inside his store in Lakewood, Colo.

Sometimes a U.S. Supreme Court decision that says less is better than one that says more. Consider the case of the Colorado baker who refused on religious grounds to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple.

In a term fraught with consequential cases, Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission brought the culture wars back to the justices' doorstep. However, a majority found a way to sidestep the showdown between the baker's right to express his religion and the gay couple's right to be free from discrimination under Colorado's anti-discrimination law.

It was a case that, in the words of one legal scholar, “clearly tore at the soul” of Justice Anthony Kennedy, who ultimately wrote the opinion for a 7-2 majority. The case, with its religion, speech and discrimination claims, presented the intersection of two lines of jurisprudence in which Kennedy has carved out his legacy. Kennedy is the closest to a First Amendment absolutist on the Roberts court, particularly in the area of speech. And, he has authored all of the court's rulings upholding the dignity and rights of gay men and lesbians.

So how did a majority of five conservative justices and two liberals come together and where the only two dissenters were liberal justices who had stood with Kennedy in gay rights decisions in the past? For the close court observer, arguments in the case in December appeared to offer a strong hint of a path forward for Kennedy and his colleagues.

Kennedy was considered the key vote to a likely 5-4 decision either for the baker or the gay couple. During the arguments, a telling moment came when Kennedy angrily questioned Colorado Solicitor General Frederick Yarger about comments by a member of the civil rights commissions at the hearing on the discrimination charge against the baker.

The commissioner, said Kennedy, claimed that “freedom of religion used to justify discrimination is a despicable piece of rhetoric.” Did the commission, the appellate court or anyone disavow that and other comments, asked Kennedy. Yarger answered in the negative.

The justice then asked Yarger: “Well, suppose we thought there was a significant aspect of hostility to a religion in this case. Could your judgment stand?” Yarger replied: “Your honor, if there was evidence that the entire proceeding was begun because of an intent to single out religious people, absolutely, that would be a problem.”

Hostility to the baker's religion became the linchpin to Kennedy's majority opinion. The baker, he wrote, was denied a neutral, free-from-bias hearing and that violated his First Amendment right.

“The neutral and respectful consideration to which (baker Jack) Phillips was entitled was compromised here, however,” wrote Kennedy. “The Civil Rights Commission's treatment of his case has some elements of a clear and impermissible hostility toward the sincere religious beliefs that motivated his objection.”

Kennedy also found that the commission had been inconsistent in its treatment of this baker and three other bakers who refused to bake a cake for a customer who wanted text and symbols degrading gays and lesbians. Those other bakers, he wrote, were not found to have discriminated.

Justices Elena Kagan and Stephen Breyer concurred in the majority opinion. Kagan, writing separately for the two, said they concurred in full. But they strategically used the concurrence to offer the commission, the state appellate court and perhaps future courts, a way to distinguish the situation involving those three nondiscriminating bakers from Phillips.

Kagan argued there was a principle that could account for the difference in result between those cases. Phillips, Kagan wrote, sells wedding cakes to opposite-sex couples but not to same-sex couples and so unlawfully discriminates under state law. The three other bakers were asked to bake a cake that they would not have sold to anyone and so did not discriminate and did not deny equal treatment, Kagan said. She took issue with the concurrence by Justice Neil Gorsuch, who was joined by Justice Samuel Alito Jr., who saw no difference between the two situations.

Gorsuch argued that, in both situations, “the effect on the customer was the same: Bakers refused service to persons who bore a statutorily protected trait—religious faith or sexual orientation.”

Kate Shaw suggested in an article that one reason Kagan and Breyer joined Kennedy's opinion may have been “simple pragmatism.” Because there was no clear answer to the difficult question about the proper balance between religious freedom and the state's power to protect gays and lesbians from discrimination, she wrote, they may have thought it wiser to wait another day and case before staking out a position by joining dissenters Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor. The latter two would have ruled for the gay couple.

And by joining Kennedy, added Shaw, the two justices, through the concurrence, “were thus able to give the Colorado commission some clear instructions: A do-over without the religious hostility and with a better explanation of its rationale could well result in a constitutionally sound victory for the same-sex couple denied their cake by Mr. Phillips. That is the power of joining an opinion: It allows justices to help shape the interpretation of that opinion by lower courts, state agencies and other bodies that have to implement the court's ruling—an influence that is difficult to have from a position of dissent.”

Kennedy's conclusion was reminiscent of his ending in his majority decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, holding the Constitution protects the right of same-sex couples to marry. He wrote in Obergefell that the First Amendment protected the right of religious organizations and persons to teach the principles central to their faiths as well as of others who oppose same-sex marriage for other reasons. At the same time, those who support same-sex marriage, he said, “may engage those who disagree with their view in an open and searching debate.”

Aware that that debate continues, Kennedy ended the baker's case, saying:“The outcome of cases like this in other circumstances must await further elaboration in the courts, all in the context of recognizing that these disputes must be resolved with tolerance, without undue disrespect to sincere religious beliefs, and without subjecting gay persons to indignities when they seek goods and services in an open market.”

Hillel Levin of the University of Georgia School of Law said the decision appeared “robust” because it was 7-2 and avoided the conservative-versus-liberal split that often marks the court's decisions in its most controversial cases. “However, the decision is a narrow, highly fact-specific one that does not offer clear guidance for future cases that are sure to arise,” added Levin. “The court, as it often does, sacrificed clarity for consensus.”

Similar cases already are moving through courts around the country and likely will continue until the justices offer that “clarity” and “clear guidance.” And, while some religious groups and other organizations opposed to same-sex marriage celebrated the baker's victory, their opponents took heart from the general principle cited by Kennedy in his majority decision and used by Kagan to open her concurrence:

“It is a general rule that [religious and philosophical] objections do not allow business owners and other actors in the economy and in society to deny protected persons equal access to goods and services under a neutral and generally applicable public accommodations law.”

Time will tell, said some legal scholars, how viable that general rule, announced in a 1990 decision by Justice Antonin Scalia, will remain.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

4th Circuit Upholds Virginia Law Restricting Online Court Records Access

3 minute read

'Where Were the Lawyers?' Judge Blocks Trump's Birthright Citizenship Order

3 minute read

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 2Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 3Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 4Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

- 5Freshfields Hires Ex-SEC Corporate Finance Director in Silicon Valley

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250