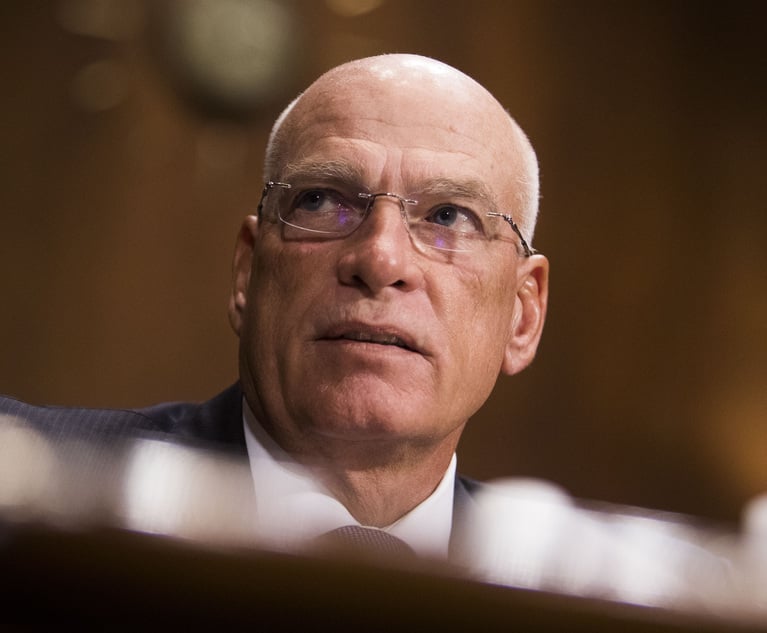

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. at the investiture of Neil Gorsuch in June 15, 2017. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / NLJ

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. at the investiture of Neil Gorsuch in June 15, 2017. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / NLJJustices Thomas and Ginsburg Now Flank Roberts on 8-Justice Bench

Inside the courtroom, there was no sense of the confirmation drama continuing to unfold across the street as the U.S. Senate awaited an FBI report on sexual assault allegations against Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh.

October 01, 2018 at 02:51 PM

4 minute read

On the first day of the new U.S. Supreme Court term, it was business not quite as usual.

Eight high-back, black leather chairs, instead of the usual nine, stood tall behind a curved mahogany bench designed to host nine justices. And as usually happens when a justice departs, seniority forces musical chairs of a sort for all but the center seat occupied by Chief Justice John Roberts Jr.

As for the chief justice, he now finds himself, following the July retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy, bookended on his right by the new senior associate justice, Clarence Thomas, and on his left, by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Inside the courtroom, there was no sense of the confirmation drama continuing to unfold across the street as the U.S. Senate awaited an FBI report on sexual assault allegations against Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. But outside, in the long line of audience hopefuls that snaked around the corner, the confirmation turmoil was a hot topic, as well as inside the court building packed with lawyers seeking admittance to the Supreme Court bar or waiting to hear the day's arguments.

Before the arguments began, the wives of Justices Thomas and Stephen Breyer took their seats in a section reserved for the justices' guests.

Roberts' first business of the day was to officially close the October 2017 term and open the October 2018 term. He then noted that today was the 25th anniversary of the investiture of Ginsburg. He congratulated her on her “distinguished service” and added, “We all look forward to sharing many more years with you in our common calling.”

Not surprisingly, after the summer hiatus, the number of lawyers waiting to be sworn into the bar was large. Judge Patricia Millett of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit—the same court on which Kavanaugh sits—introduced and attested to the qualifications of members of the Military Spouse J.D. Network, which, since 2011, has advocated for licensing accommodations for military spouses, including bar membership without additional examinations. A group from New York Law School, among others, also was admitted to the Supreme Court bar.

With bar admittances wrapped up, the justices plunged into the arguments of the day—classic examples of the court's bread-and-butter business: statutory interpretation. How should “critical habitat” in the Endangered Species Act be defined? The lives of dusky gopher frogs may well depend on the answer. And what is the meaning of “also means” in the Age Discrimination in Employment Act? The court's interpretation could bring state agencies and political subdivisions of all sizes under the job bias law.

The justices gave an equally hard time to Mayer Brown's Timothy Bishop and Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler in the frog case, Weyerhaeuser v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. But it appeared that in arguing for broad coverage by the age-discrimination law, Stanford Law School's Jeffrey Fisher, counsel to John Guido, just might have the edge over E. Joshua Rosenkranz, the Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe partner representing the Mount Lemmon Fire District in Arizona.

With an eight-justice court, there is always the potential for a 4-4 split decision, which leaves the lower court ruling in place.

Read more:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Paul Weiss’ Shanmugam Joins 11th Circuit Fight Over False Claims Act’s Constitutionality

‘A Force of Nature’: Littler Mendelson Shareholder Michael Lotito Dies At 76

3 minute read

US Reviewer of Foreign Transactions Sees More Political, Policy Influence, Say Observers

'Unlawful Release'?: Judge Grants Preliminary Injunction in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250