DOJ Memo Blesses Whitaker Appointment as Acting AG

The Office of Legal Counsel's thumbs-up for Whitaker will hardly settle the debate over the legitimacy of Whitaker's appointment.

November 14, 2018 at 10:02 AM

5 minute read

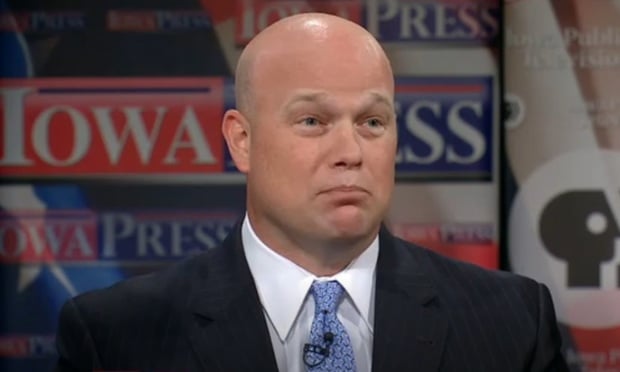

Then-candidate Matt Whitaker on Iowa public television in 2014. (Photo: PBS screen grab)

Then-candidate Matt Whitaker on Iowa public television in 2014. (Photo: PBS screen grab)

The Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel signed off on Matthew Whitaker's appointment as acting attorney general Wednesday, issuing a public opinion that is unlikely to quell the debate over the constitutionality of his installation by President Donald Trump.

The memo comes less than a week after Whitaker stepped into the role, taking the place of Jeff Sessions who resigned from his role as Attorney General at the White House's request. Trump's designation of Whitaker as Acting Attorney General—he previously served as Sessions' chief of staff—has stirred debate over whether his placement required U.S. Senate confirmation.

Some legal scholars, from the left and right, have said Whitaker's installation violated the Constitution's appointments clause, because his role as acting attorney general would have made him a principal officer under the clause. Such a role requires a presidential nomination and the Senate's “advice and consent.”

“Mr. Whitaker's designation as Acting Attorney General accords with the plain terms of the Vacancies Reform Act, because he had been serving in the Department of Justice at a sufficiently senior pay level for over a year,” the Justice Department's opinion, written by assistant Attorney General Steven Engel, said.

“Although the Attorney General is a principal officer, it does not follow that an Acting Attorney General should be understood to be one,” Engel added. “While a person acting as the Attorney General surely exercises sufficient authority to be an 'Officer of the United States,' it is less clear whether the Acting Attorney General is a principal office.”

In approving Whitaker's appointment, the OLC referred back to the office's 2003 opinion, when it sanctioned the designation of an acting director of the Office of Management and Budget. While the director of the agency is a principal officer, the OLC found at the time that the acting director qualified as an inferior one, satisfying the Constitution's Appointments Clause.

“If the newly installed Deputy Director of the CFPB could lawfully have become the Acting Director, then the Chief of Staff to the Attorney General may serve as Acting Attorney General in the case of a vacancy,” Engel wrote.

Engel also said that in a “brief survey of the history,” his team of lawyers identified at least 160 instances before 1860 where non-Senate confirmed officials acted in roles that require Senate confirmation, including cabinet secretary roles. Engel found that in 1860, a non-Senate confirmed acting assistant attorney general stepped in as acting attorney general, although the Justice Department, created in 1870, had not at the time existed.

Still, the Office of Legal Counsel's thumbs-up for Whitaker will hardly settle the debate over the legitimacy of his appointment. Liberal and conservative lawyers alike have questioned whether his installation was valid, arguing his role atop the Justice Department and overseeing the special counsel probe would have required him to be confirmed by the Senate.

In a New York Times column last week, Neal Katyal of Hogan Lovells and George Conway of Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz contend that Whitaker's appointment would put him in a position where he would have to report to only one person: the president. Given that unique arrangement, he could only be deemed a principal officer under the Appointments Clause, which would have required that he had been confirmed by the U.S. Senate, they argued.

Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh sought a federal judge's intervention on Tuesday, when his office filed a motion asking a court to declare Rosenstein, not Whitaker, as the rightful acting attorney general. The filing was entered as part of a separate Affordable Care Act-related lawsuit against the administration in September.

Defenders of Whitaker's leadership have argued that the Federal Vacancies Reform Act empowers Trump to appoint Whitaker as acting attorney general. Under that 1998 federal statute, when a senior agency official resigns from his or her position, the president can appoint a temporary official from the agency to temporarily fill in that role.

Even under that statute, the deputy attorney general—Rod Rosenstein, in this case—would be the expected choice to fill in as acting attorney general. The question remains as to whether Trump acted within his legal authority by opting to name Whitaker over Rosenstein.

Former George W. Bush administration official John Yoo, in a column published Tuesday in The Atlantic, noted Whitaker's appointment met the terms of the Vacancies Reform Act. Even then, he argued, it would be a violation of the Constitution Appointments Clause.

The OLC disagreed Wednesday morning, writing: “It is no doubt true that Presidents often choose acting principal officers from among Senate-confirmed officers. But the Constitution does not mandate that choice.”

In addition, Whitaker faces separate calls to recuse himself from overseeing the Mueller probe, even if he is allowed to lead the Justice Department. Some say Whitaker's past criticisms of the Mueller probe, as well as his past ties to Trump campaign aide Sam Clovis—a witness in the special counsel probe—disqualify him from overseeing the investigation.

Read the memo:

Read more:

Maryland Files First Court Challenge to Trump's Acting AG Appointment

DOJ's Whitaker Gets Mixed Reviews From Ex-Partners, Iowa Lawyers

Trump's 3rd Circuit Nominee Grilled Over Ties to Chris Christie, Bridgegate

Neomi Rao, Trump's Deregulatory Leader, Gets DC Circuit Nod to Replace Kavanaugh

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Something Else Is Coming': DOGE Established, but With Limited Scope

Supreme Court Considers Reviving Lawsuit Over Fatal Traffic Stop Shooting

US DOJ Threatens to Prosecute Local Officials Who Don't Aid Immigration Enforcement

3 minute read

US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Who Are the Judges Assigned to Challenges to Trump’s Birthright Citizenship Order?

- 2Litigators of the Week: A Directed Verdict Win for Cisco in a West Texas Patent Case

- 3Litigator of the Week Runners-Up and Shout-Outs

- 4Womble Bond Becomes First Firm in UK to Roll Out AI Tool Firmwide

- 5Will a Market Dominated by Small- to Mid-Cap Deals Give Rise to a Dark Horse US Firm in China?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250