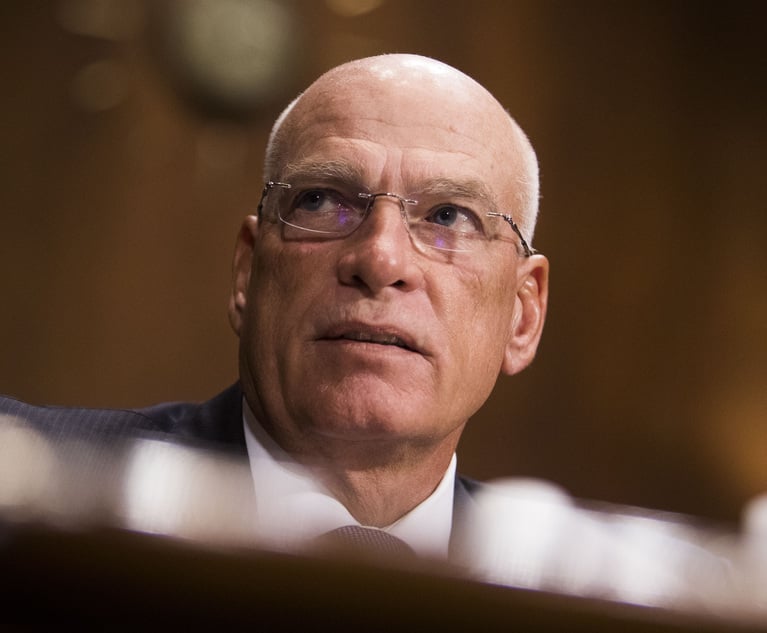

Rod Rosenstein, Deputy Attorney General at the U.S. Department of Justice, speaks October 2017 at the 18th Annual Legal Reform Summit, held at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / NLJ

Rod Rosenstein, Deputy Attorney General at the U.S. Department of Justice, speaks October 2017 at the 18th Annual Legal Reform Summit, held at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / NLJRod Rosenstein Expands Power to Give Cooperation Credit in White-Collar Cases

"The most important aspect of our policy is that a company must identify all wrongdoing by senior officials, including members of senior management or the board of directors, if it wants to earn any credit for cooperating in a civil case," Rosenstein said Thursday in remarks in Washington, D.C.

November 29, 2018 at 12:42 PM

4 minute read

U.S. Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein on Thursday eased the Justice Department's “all or nothing” approach to assessing cooperation in civil cases, announcing revised policies that give prosecutors more discretion to award credit to companies even when they do not identify every employee who might be potentially culpable.

“The most important aspect of our policy is that a company must identify all wrongdoing by senior officials, including members of senior management or the board of directors, if it wants to earn any credit for cooperating in a civil case,” Rosenstein said in remarks in Washington, D.C., at the 35th International Conference on the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. “If a corporation wants to earn maximum credit, it must identify every individual person who was substantially involved in or responsible for the misconduct.”

Read Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein's full remarks here:

Reflecting statements of Obama-era leadership at Main Justice, Rosenstein said the pursuit of individual corporate leaders responsible for misconduct will be a “top priority.” Any company that wants cooperation credit in a criminal case, Rosenstein said, “must identify every individual who was substantially involved in or responsible for the criminal conduct.”

He added: “In response to concerns raised about the inefficiency of requiring companies to identify every employee involved regardless of relative culpability, however, we now make clear that investigations should not be delayed merely to collect information about individuals whose involvement was not substantial and who are not likely to be prosecuted.”

Rosenstein's remarks came a year after the Justice Department began reviewing its policy for assessing individual accountability in corporate cases.

The revised policy, he said, acknowledges that the “all or nothing” approach to identifying all culpable employees in the civil arena can drag out investigations and drain Justice Department resources. The department's review, Rosenstein said, revealed that the policy for holding individuals accountable was not “strictly enforced in some cases because it would have impeded resolutions and wasted resources.”

Rosenstein said the “all or nothing” approach to giving cooperation credit can prove particularly unworkable in civil cases, where the government's primary goal is to recover money.

Prosecutors, he said, need flexibility to accept settlements that address harm and deter future violations and cannot take the time to pursue civil cases against every individual who may be liable for misconduct. The policy gives prosecutors discretion to offer some cooperation credit even if a company does not qualify for maximum credit.

“The idea that a company that engaged in a pattern of wrongdoing should always be required to admit the civil liability of every individual employee as well as the company is attractive in theory, but it proved to be inefficient and pointless in practice,” Rosenstein said.

“When we allow only a binary choice—full credit or no credit—experience demonstrates that it delays the resolution of some cases while providing little or no benefit,” he added.

➤➤ Get more reporting on developments in compliance, enforcement and government affairs with Compliance Hot Spots, a weekly email briefing from Law.com. Sign up here.

Read more:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Unlawful Release'?: Judge Grants Preliminary Injunction in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute read

Federal Judge Grants FTC Motion Blocking Proposed Kroger-Albertsons Merger

3 minute read

Frozen-Potato Producers Face Profiteering Allegations in Surge of Antitrust Class Actions

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1First-of-Its-Kind Parkinson’s Patch at Center of Fight Over FDA Approval of Generic Version

- 2The end of the 'Rust' criminal case against Alec Baldwin may unlock a civil lawsuit

- 3Solana Labs Co-Founder Allegedly Pocketed Ex-Wife’s ‘Millions of Dollars’ of Crypto Gains

- 4What We Heard From Litigation Leaders This Year

- 5What's Next For Johnson & Johnson's Talcum Powder Litigation?

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250