Dismantling the 'Criminal Justice Monster'

Pulitzer Prize-winning author James Forman Jr. discusses the state of criminal justice reform and the incremental policies necessary to dismantle mass incarceration.

December 28, 2018 at 04:24 PM

8 minute read

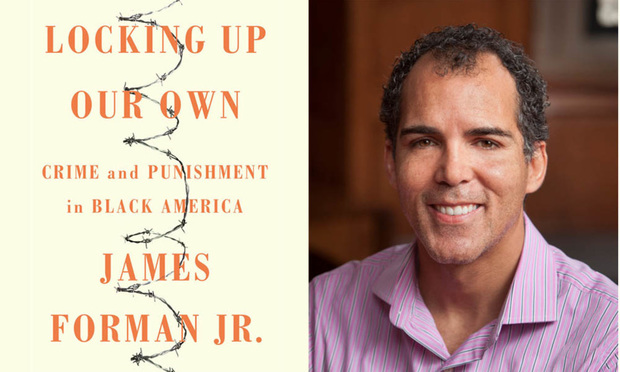

Locking Up Our Own

Locking Up Our Own

When Yale law professor and Pulitzer Prize-winning author James Forman Jr. got to law school, he knew he wanted to be a civil rights lawyer, but he wasn't aware that pursuit would take him down the criminal justice reform career track.

At the time, premier civil rights organizations in the 1990s like the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund had subject matter areas in employment, school desegregation, housing, voting rights and the death penalty, but no overall focus on criminal justice, Forman said. During an internship at the Legal Defense Fund in his first summer at Yale Law, Forman began to realize some of the injustices being highlighted in death penalty cases were true more broadly across the criminal justice system. With that knowledge, he pursued post-law school work as a public defender.

Forman's book, "Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America," weaves an anecdotal narrative from his experience defending his clients, embedded with historical accounts and statistics to tell the story about how America's tough-on-crime policies were borne out of communities grappling with ways to address violent crime and drug addictions. Forman's account attempts to understand how majority-black cities ended up incarcerating so many of their own in the hopes of giving readers a richer understanding of mass incarceration rates and the incremental policies that led to them.

He spoke with the NLJ about criminal justice reform and the policy prescriptions necessary to overcome mass incarceration. What follows are highlights from that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

The National Law Journal: You mention briefly how President Donald Trump as a candidate displayed very tough-on-crime rhetoric during his campaigns. Are you surprised at all by his embrace of criminal justice reform?

James Forman Jr.: I think the credit goes to a lot of advocates who have had his ear, and have really, really pushed hard—celebrities, and some prominent conservatives and other kinds of progressive activists—so I think they deserve credit for sort of persuading him that this was something that he should get behind.

In terms of the legislation, I think it's a small but important step. It's limited because it's limited to the federal government, and it's limited in scope even within the federal government. Having said that, I believe—and as you know I argue in my book—that this is a criminal justice monster that was built incrementally and it's going to have to be dismantled incrementally. So I don't discount changes because they're incremental, I think of course you always want to push for more, because if you can make a bigger inroad, if you can reduce more sentences, if you can have more funding for robust education programs or second chance programs, that's better than less but some is better than none.

NLJ: To that end, you highlight how mass incarceration is really more of a local governance issue than a federal one, as about 88 percent of prisoners are in state or local jails. Is there any commonality in respect to the states that have had success reducing prison populations?

JF: It's actually all different. There are a hundred different things that you can do, different policy levers that you can pull, that will make a difference. And I think what you've seen in the states that have reduced their prison populations is they have picked from that list of 100, but they've all picked a different set of like six or eight or 10 things. So, I think some states, for example, have done what the federal government is doing in a sense, which is reducing the sentences, offering opportunities for release for people who have been serving long sentences. So that's something that more and more states could look to. We have an increasingly geriatric prison population, and many of those folks were sentenced at a time when judges thought they were going to serve fewer years than they actually ended up serving.

For example, I was just in Jessup, Maryland, at a prison there talking to a group of lifers. These guys committed serious crimes. Most of them committed some form of homicide. Lots of aggravating circumstances, you know, you commit felony murder, you commit a robbery, and someone is shot during the course of the robbery, you didn't pull the trigger, but that's still first-degree murder. So a number of them had cases like that. Judges gave them sentences for life and said at the sentencings, "I want you to remember this day and to dedicate yourself to turning this community around and helping honor the memory of this victim." So the judges thought they were going to be released because when they were sentencing them, parole was available. And then, in the '90s, as a part of this tough-on-crime rhetoric, Democratic candidate for governor Parris Glendening said, "There will never be parole in this state again; I will not allow anyone serving a life sentence to get parole." Well, so those guys, some of whom were about to get parole, are now still in 20 years later, because no governor has been willing to go back on that pledge that was made in 1995. So things like that, restoring parole eligibility for people who are serving long sentences is something that you can think about at the back end that would make a big difference.

NLJ: You discuss how a lot of the problems that led to incarceration were misidentified as law enforcement issues rather than public health issues. Do you see any issues today that are miscategorized as law enforcement issues?

JF: I don't want to overstate the progress. There has been a recent reduction of the number of people in prison in this country, but it's still three to four times what it was in the early 1970s, controlling for population growth, et cetera. We sit atop a really unparalleled experiment in human history which is what happens if an incredibly wealthy democracy decides to lock up a higher percentage of its citizens than any other country has in the history of the world. And that's what we're talking about in the United States still, even with the percentage of declines in the number of states that I mentioned. So in essence, I would say we're still making most of the mistakes that I mention in the book.

We talk about drug treatment now in the context of the opioid epidemic, there's been much more discussion of the importance of treatment, but it's still the case in most cities and states, that there are six-month to 12-month waiting lists for available, publicly funded treatment programs. In most places, there's anywhere between three to 10 times the number of people who need treatment than spaces that are available for it. And in most cities, counties and states, the treatment being offered is woefully inadequate, substandard and not up to the task.

NLJ: I wanted to ask about pretext for police encounters. You highlighted that as one of the main culprits. How do you fix that? Is that just a matter of police departments stopping it?

JF: Some of these things we're talking about are hard, but some of them are very straightforward. And the pretext stop is one of those that can be stopped by stopping it. It's not something that has always been done historically, and it's not something that's done routinely. It's not done in equal measure in all parts of the country, and it's not done in equal measure against all types of citizens. It's overwhelmingly concentrated on black people, on Hispanic people, and within those communities most especially on young or low-income folks in those communities. But what we know from the research, in city after city where this has been documented, black and Hispanic people are more likely than white people to be searched without consent after a pretext stop. And when they're searched, they are less likely to be found with contraband.

I was just looking at numbers from San Francisco. In San Francisco, black people are about four times more likely to be searched without consent after a stop and Hispanic people are about three times more likely to be searched. But when they're searched, black people are about half as likely to have contraband on them. So the whole premise of this routine is that you're stopping people because they're at greatest risk of having contraband, but it turns out that's not true. So if that isn't true, then all that's happening is people are being burdened by the humiliation and the stigma, the degradation of being singled out by law enforcement and forced to subject themselves to incredibly humiliating stops and searches and for no law enforcement benefits.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

From the Bench to the Booth: 2 Former Judges Now at Gibson Dunn Pair for Podcast

'Lawyers Are Lovely as Clients': Meet the Munger Tolles Trial Attorney Defending Law Firms

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.