Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. (Photo by David Handschuh/ALM)

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. (Photo by David Handschuh/ALM)No Shortcut to Copyright Registration, High Court Rules

Applying and paying is not enough to clear the way for an infringement suit, the U.S. Supreme Court justices ruled in a blow to owners. The copyright register must also sign off, which can take weeks.

March 04, 2019 at 06:41 PM

3 minute read

Copyright owners will have to wait for the registration process to play out before suing for infringement, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously Monday.

Owners had asked the Supreme Court to adopt the Ninth and Fifth circuits' practice of considering a work registered once an application was submitted to the Copyright Office and the fees paid. But the Supreme Court agreed with the Eleventh and Tenth circuits that the copyright register must complete the application, a process that typically requires about seven weeks.

“The registration approach, we conclude, reflects the only satisfactory reading of Section 411(a)'s text,” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in Fourth Estate Public Benefit v. Wall-Street.com.

“Today's decision wholeheartedly affirms the original text of the Copyright Act, as well as Congress' desire to promote early and extensive copyright registration,” Stris & Maher's Peter Stris, who had the winning argument for Wall-Street.com, said in a written statement.

Fourth Estate was represented by Aaron Panner of Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick.

Reed Smith partner Keyonn Pope, who's not involved in the case, said the decision may prompt content creators to “seek registration earlier and more often,” which could result in additional pressure on the Library of Congress.

Copyright attaches to works when they're fixed in a tangible medium, but registration is a prerequisite to suing for infringement under Section 411(a) of the Copyright Act. Owners will still be able to seek damages back to and even prior to registration, but as a practical matter injunctions won't be available for most works until they're fully registered.

Fourth Estate is an independent news organization that licenses its content to a syndicate which in turn licensed it to Wall-Street.com, a financial news website. Wall-Street terminated the arrangement but allegedly continued distributing some of Fourth Estate's works. Fourth Estate applied for copyright registration and sued, but the Eleventh Circuit ruled that the suit had to be dismissed because registration was incomplete.

Amicus groups such as the National Music Publishers' Association argued to the Supreme Court that having to wait for registration to play out while a work is distributed all over the internet can have “a devastating effect” on copyright holders.

Ginsburg noted that in 1993 Congress considered, but declined to adopt, a proposal to allow suit immediately upon submission of an application. And in 2005 it created a “preregistration” option for works that are especially vulnerable to pre-distribution infringement.

“Time and again, then, Congress has maintained registration as prerequisite to suit, and rejected proposals that would have eliminated registration or tied it to the copyright claimant's application instead of the register's action,” Ginsburg wrote.

She acknowledged that processing time was only one or two weeks when the statutory scheme was originally enacted in 1956. She said the current delays appear to be due largely to “staffing and budgetary shortages that Congress can alleviate, but courts cannot cure.”

“Unfortunate as the current administrative lag may be,” she wrote, “that factor does not allow us to revise Section 411(a)'s congressionally composed text.”

Read more:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Pre-Internet High Court Ruling Hobbling Efforts to Keep Tech Giants from Using Below-Cost Pricing to Bury Rivals

6 minute read

Will Khan Resign? FTC Chair Isn't Saying Whether She'll Stick Around After Giving Up Gavel

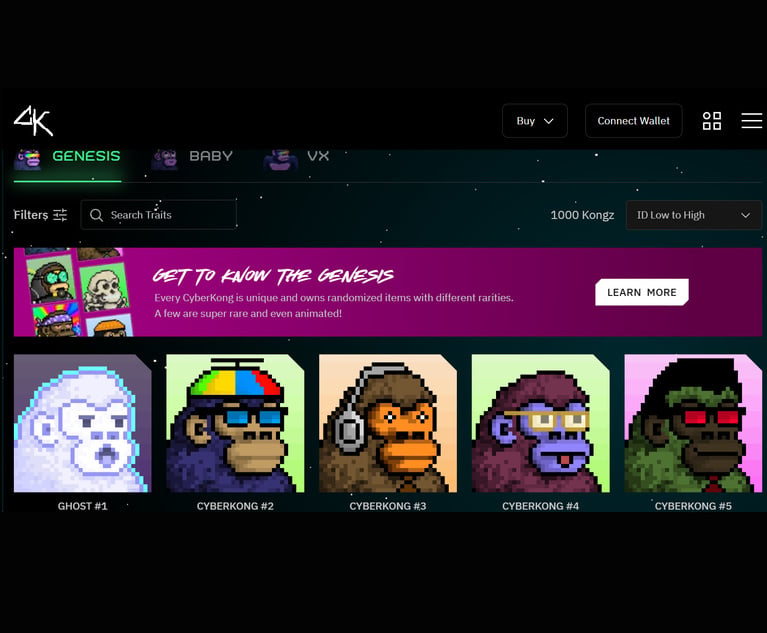

‘Badge of Honor’: SEC Targets CyberKongz in Token Registration Dispute

3 minute read

$25M Grubhub Settlement Sheds Light on How Other Gig Economy Firms Can Avoid Regulatory Trouble

8 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Senate Judiciary Dems Release Report on Supreme Court Ethics

- 2Senate Confirms Last 2 of Biden's California Judicial Nominees

- 3Morrison & Foerster Doles Out Year-End and Special Bonuses, Raises Base Compensation for Associates

- 4Tom Girardi to Surrender to Federal Authorities on Jan. 7

- 5Husch Blackwell, Foley Among Law Firms Opening Southeast Offices This Year

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250