'Laughter Is a Blood Sport' at the Supreme Court, Scholars Say in New Study

Humor at the U.S. Supreme Court is less an "indication not of lighthearted, good-natured jesting" than a "rhetorical weapon," legal scholars Tonja Jacobi and Matthew Sag contend.

March 08, 2019 at 12:18 PM

5 minute read

Justice Antonin Scalia (2010) Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

Justice Antonin Scalia (2010) Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

U.S. Supreme Court justices direct their humorous quips and barbs most often at advocates with whom they disagree, lawyers who are losing their arguments and attorneys who do not have experience at the high court, according to an exhaustive new study.

In their study “Taking Laughter Seriously at the Supreme Court,” two scholars—Tonja Jacobi of Northwestern University School of Law and Matthew Sag of Loyola University of Chicago Law School—built and analyzed a database of every Supreme Court oral argument transcript from 1955 to 2017.

Jacobi and Sag said they found more than 9,000 instances of laughter in 6,864 cases over 63 years. Transcripts of hearings include a reference to “laughter.”

“From our analysis of eight terms, we believe that laughter at Supreme Court oral arguments tends to be an indication not of lighthearted, good-natured jesting by a superior to an inferior, but of a rhetorical weapon being used by a superior against an inferior, by a justice as a form of advocacy against an advocate arguing a side the justice likely will oppose, or when an advocate is inexperienced or doing badly,” the authors said. In other words: “Laughter is a blood sport at the court.”

Jacobi and Sag said they listened to many high court arguments and heard patterns in the justices' comments that provoked laughter. “We were interested in the way humor is used—whether it is part of advocacy by the justices, like their interruptions. And sure enough it really is part of that advocacy process,” Jacobi said.

Sag said “the idea that the judges who get the most laughs are somewhat funny never struck me as that plausible. Courtroom humor is really about people being uncomfortable for being put on the spot, occasionally there is some absurdism.”

If advocates familiarize themselves with the kinds of humor that appeal to the justices, they can think more about how to respond, Sag said. “In statutory interpretation cases, it's almost inevitable Justice Alito will make some joke about Congress,” he said. “When a case lends itself to different hypothetical situations, one form of humor is exaggerations, and when you see that kind of rhetoric coming, you are better prepared to answer it.”

Here are a few conclusions from their analysis:

>> The modern Supreme Court—the Rehnquist and Roberts eras—accounts for two-thirds of laughter moments, despite covering less than half of the time period studied. For example, the Warren and Burger Court justices accounted for only 6 percent and 14 percent of judicial courtroom humor, respectively, whereas the Rehnquist and Roberts courts accounted for 48 percent and 32 percent, respectively, of comments by justices inspiring laughter.

>> Looking closely at the rate of laughter associated with each justice over their time on the bench, the study confirmed that Justice Antonin Scalia played a significant role in the increased incidence of laughter, but his influence was by no means dominant.

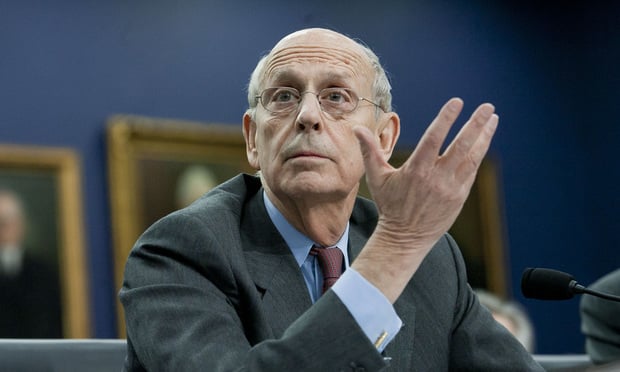

Justice Stephen Breyer testifies in 2015. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

Justice Stephen Breyer testifies in 2015. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL>> Ranking the justices by mean laughter per oral argument 1955-2017: Scalia holds the first slot and Breyer was second. “Justice Scalia is often lauded for being so funny, but if laughter is a weapon, that means that Justice Scalia is simply the most acerbic, and the most strategic at this particular type of advocacy,” according to the study. Jacobi and Sag said about Breyer: “By far the majority of his jokes involve either silliness or self-deprecation.” Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. was third, followed by Justice Neil Gorsuch and then Justices Elena Kagan, David Souter, Felix Frankfurter, William Rehnquist, Anthony Kennedy and John Paul Stevens. Frankfurter is the only justice from the earlier part of the data set who mirrors the behavior of the modern justices.

>> There is a large effect of making jokes during the time of losing advocates. But neutrality toward advocates makes Roberts “remarkable.”

>> The justices are significantly more likely to make the kind of comments that provoke laughter in the courtroom while a “novice,” making their first argument, is speaking, and significantly less likely to do so during the time of the advocates that the study classifies as “heroes,” a lawyer who has argued at least 11 times.

>> So considering all of the data, what does the “funniest justice” title mean? “In general, it means that these justices are the most pointed advocates,” Jacobi and Sag concluded. “Justice Breyer, and to a lesser extent Justice Kagan, are exceptional in being self-deprecating, but we have shown that overall humor of the court is pretty mean.”

Read more:

How to Tell a Justice You Are Wrong

Everything Was 'Excellent' In Key Patent Case at Supreme Court

Hypothetical President, Grammar Lessons & 'Beautiful' Hovercrafts: Laugh Lines

What Makes Chief Justice John Roberts Lose His Cool

Kagan Says Repeat Players at SCOTUS 'Know What It Is We Like'

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Religious Discrimination'?: 4th Circuit Revives Challenge to Employer Vaccine Mandate

2 minute read

Standing Spat: Split 2nd Circuit Lets Challenge to Pfizer Diversity Program Proceed

Fight Over Amicus-Funding Disclosure Surfaces in Google Play Appeal

4th Circuit Revives Racial Harassment Lawsuit Against North Carolina School District

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250