Justice Breyer, in Dissent, Tangles With Kavanaugh Over Immigration

"The question before us is not 'narrow,'" Justice Stephen Breyer said in his dissent, responding to Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

March 19, 2019 at 02:25 PM

4 minute read

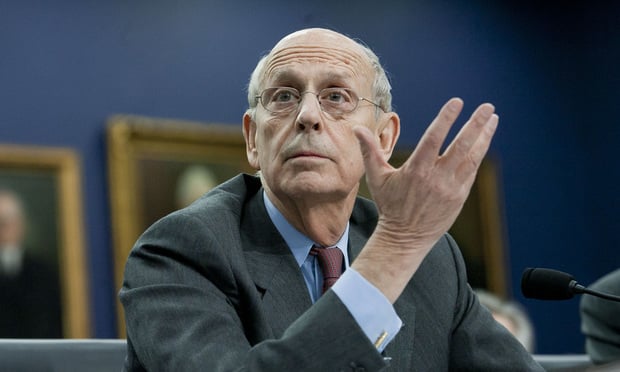

Justice Stephen Breyer testifies before Congress in 2015. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

Justice Stephen Breyer testifies before Congress in 2015. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

Springtime decisions in the U.S. Supreme Court usually begin to reveal sharp differences among the justices. On Tuesday, a concurrence by Justice Brett Kavanaugh in an important immigration ruling struck a nerve in Justice Stephen Breyer.

In Nielsen v. Preap, the court's conservative majority ruled the Trump administration had authority to arrest and detain without bond hearings those immigrants who had completed their criminal sentences even after they had spent years in the community. Those immigrants could be held until their removal had been decided by an immigration court.

Kavanaugh wrote separately only to say what the case was not about. In three pages, he used the phrase “this case is not about” four times, and he declared the question before the court is “narrow.” He added: “No constitutional issue is presented. The issue before us is entirely statutory and requires our interpretation of the strict 1996 illegal-immigration law passed by Congress and signed by President Clinton.”

Breyer, writing in dissent, disputed Kavanaugh's assertion.

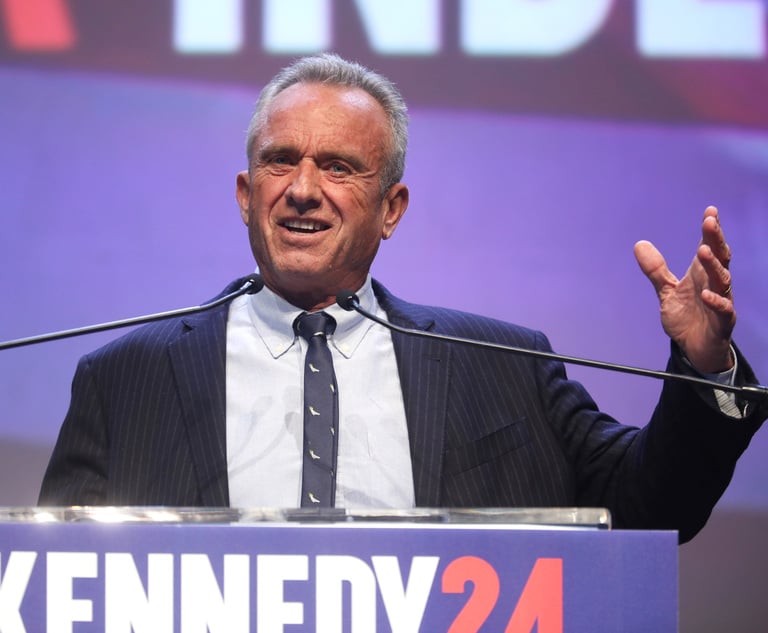

Brett Kavanaugh was nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court at a ceremony in the East Room. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / NLJ

Brett Kavanaugh was nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court at a ceremony in the East Room. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / NLJReading portions of his dissent from the bench, Breyer said the case is about “basic American legal values,” including the government's duty not to deprive anyone of liberty without due process of law “and the longstanding right of virtually all persons to receive a bail hearing.”

Many of the immigrants may have been convicted of minor crimes and, after serving their sentences, put down roots in their communities, he noted.

“Moreover, for a high percentage of them, it will turn out after months of custody that they will not be removed from the country because they are eligible by statute to receive a form of relief from removal such as cancellation of removal,” Breyer wrote. “These are not mere hypotheticals. Thus, in terms of potential consequences and basic American legal traditions, the question before us is not a 'narrow' one.”

Near the end of his dissent, Breyer, again citing Kavanaugh, wrote: “To reiterate, the question before us is not 'narrow.'” He concluded: “I fear that the court's contrary interpretation will work serious harm to the principles for which American law has long stood.”

Justice Samuel Alito Jr., who wrote for the majority, did not in his 26-page opinion directly address Breyer's constitutional concerns. He did say the plaintiffs could have but did not raise a “head-on” constitutional challenge to §1226(c) of the federal immigration law.

“Our decision today on the meaning of that statutory provision does not foreclose as-applied challenges—that is, constitutional challenges to applications of the statute as we have now read it,” Alito wrote.

Read more:

New Conservative Lawyers' Group 'Checks and Balances' Bristles at Trump

Chief Justice Roberts Joins Liberal Wing to Snub Alabama Court in Death Case

Writing Styles of Gorsuch and Kavanaugh Revealed in Arbitration Rulings

'With Respect,' Justice Breyer Blasts Immigration Ruling in Rare Oral Dissent

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Government Attorneys Face Reassignment, Rescinded Job Offers in First Days of Trump Administration

4 minute read

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Am Law 200 Firms Announce Wave of D.C. Hires in White-Collar, Antitrust, Litigation Practices

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1X Faces Intense Scrutiny as EU Investigation Races to Conclusion & Looming Court Battle

- 2'Nation is in Trouble': NY Lawmakers Advance Bill to Set Parameters for Shielding Juror IDs in Criminal Matters

- 3Margolis Edelstein Broadens Leadership With New Co-Managing Partner

- 4Menendez Asks US Judge for Bond Pending Appeal of Criminal Conviction

- 5Onit Acquires Case and Matter Management Software Provider Legal Files Software

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250