Ninth Circuit Upholds CFPB Structure in Ordering Law Firm to Comply With Investigation

The court ruled that a law firm under investigation for allegedly violating telemarketing rules must comply with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's demands.

May 06, 2019 at 04:39 PM

3 minute read

The original version of this story was published on The Recorder

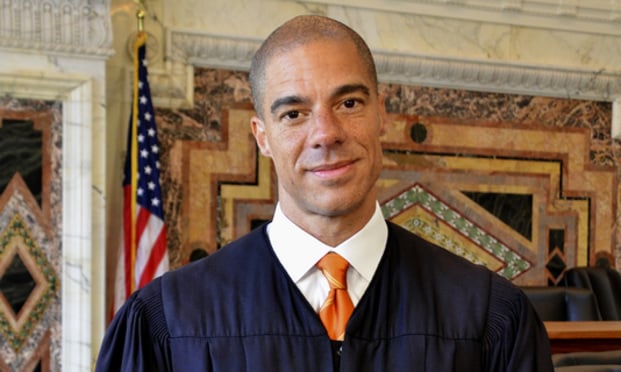

Judge Paul Watford of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Courtesy photo

Judge Paul Watford of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Courtesy photo

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, ruling that a law firm under investigation for allegedly violating telemarketing rules must comply with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's demands, has turned back a challenge to the constitutionality of the agency's structure.

The court affirmed a district court's ruling ordering Seila Law's compliance with the CFPB's civil investigative demand (CID), rejecting the law firm's arguments that the bureau is unconstitutionally structured and that it had no authority to issue the CID.

According to Ninth Circuit Judge Paul J. Watford's opinion, the CFPB issued Seila seven interrogatories and four requests for documents, which it refused to answer. The CFPB subsequently filed a petition in the Central District of California to enforce compliance, which U.S. District Judge Josephine L. Staton granted, subject to one modification.

Seila argued that the CFPB's structure violates the Constitution's separation-of-powers doctrine because it is run by a director who exercises executive power but can only be removed by the president for cause—“inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.”

Citing two U.S. Supreme Court cases, Humphrey's Executor v. United States and Morrison v. Olson, Watford said the CFPB's structure is constitutionally permissible.

Watford said the arguments in Humphrey's were similar to the case at hand, only Humphrey's involved the Federal Trade Commission. The court in that case held that the FTC exercised mostly quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial powers, rather than purely executive powers and maintained independence from the president's control.

“Like the FTC, the CFPB exercises quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial powers, and Congress could therefore seek to ensure that the agency discharges those responsibilities independently of the president's will,” Watford said, adding that the Supreme Court has noted “the CFPB acts in part as a financial regulator, a role that has historically been viewed as calling for a measure of independence from executive branch control.”

Citing Morrison, Watford said there were still differences between the FTC and the CFPB.

“The most prominent difference between the two agencies is that, while both exercise quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial powers, the CFPB possesses substantially more executive power than the FTC did back in 1935,” Watford said. “But Congress has since conferred executive functions of similar scope upon the FTC, and the court in Morrison suggested that this change in the mix of agency powers has not undermined the constitutionality of the FTC. Indeed, in Morrison the court upheld the constitutionality of a for-cause removal restriction for an official exercising one of the most significant forms of executive authority: the power to investigate and prosecute criminal wrongdoing.”

Anthony Bisconti of Bienert Katzman in San Clemente represents Seila and did not respond to a request for comment.

The CFPB also did not respond to a request for comment.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump Administration Faces Legal Challenge Over EO Impacting Federal Workers

3 minute read

US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

3 minute read

Private Equity Giant KKR Refiles SDNY Countersuit in DOJ Premerger Filing Row

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 15th Circuit Considers Challenge to Louisiana's Ten Commandments Law

- 2Crocs Accused of Padding Revenue With Channel-Stuffing HEYDUDE Shoes

- 3E-discovery Practitioners Are Racing to Adapt to Social Media’s Evolving Landscape

- 4The Law Firm Disrupted: For Office Policies, Big Law Has Its Ear to the Market, Not to Trump

- 5FTC Finalizes Child Online Privacy Rule Updates, But Ferguson Eyes Further Changes

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250