The U.S. solicitor general's petition in a trademark dispute over the mark “FUCT.”

The U.S. solicitor general's petition in a trademark dispute over the mark “FUCT.”'Immoral' Trademarks Like 'FUCT' Are Allowed, Divided US Supreme Court Says

Justice Sonia Sotomayor said in a partial dissent: “The court's decision today will beget unfortunate results."

June 24, 2019 at 10:30 AM

4 minute read

A divided U.S. Supreme Court on Monday said the First Amendment prohibits the U.S. government from denying intellectual property protection to “immoral” or “scandalous” trademarks, such as the name of the clothing line “FUCT” that was in the case before the justices.

Ruling in Iancu v. Brunetti, the justices said the Lanham Act, which bans registration of “immoral … or scandalous matter,” violates the free speech rights of clothing designer Erik Brunetti.

“There are a great many immoral and scandalous ideas in the world (even more than there are swearwords), and the Lanham Act covers them all. It therefore violates the First Amendment,” Justice Elena Kagan wrote for the 6-3 majority.

The court's decision followed the court's trend of ruling in favor of free speech. Just two years ago, in Matal v. Tam, the court ruled that disparaging marks could not be denied registration under the Lanham Act.

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. dissented in part, asserting that “standing alone, the term 'scandalous' need not be understood to reach marks that offend because of the ideas they convey; it can be read more narrowly to bar only marks that offend because of their mode of expression—marks that are obscene, vulgar, or profane.”

Justice Stephen Breyer joined Roberts and also joined a partial dissent by Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

Sotomayor wrote, “The court's decision today will beget unfortunate results. … The government will have no statutory basis to refuse (and thus no choice but to begin) registering marks containing the most vulgar, profane, or obscene words and images imaginable.”

The Brunetti case drew many briefs in which words that were even more explicit than FUCT were mentioned, but the words were avoided during oral argument.

To prove the inconsistent handling of similar trademarks, Brunetti's counsel of record John Sommer listed 34 words that might sound scandalous. Words like FCUK, FWORD, and WTF IS UP WITH MY LOVE LIFE? have been granted trademarks.

But in his brief, Sommer dropped an unusual footnote that reassured the justices they wouldn't have to hear the words he wrote about. “It is not expected that it will be necessary to refer to vulgar terms during argument,” Sommer wrote. “If it should be necessary, the discussion will be purely clinical, analogous to when medical terms are discussed.”

During oral argument April 15, Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart, who was defending the constitutionality of rejecting Brunetti's trademark, found a creative way of describing the word without saying it. “This mark,” Stewart said to the justices, “would be perceived by a substantial segment of the public as the equivalent of the profane past participle form of a well-known word of profanity and perhaps the paradigmatic word of profanity in our language.”

Roberts who has two teenage children old enough to have heard if not spoken expletives, sympathized with the plight of “parents who are trying to teach their children not to use those kinds of words” who might see people wearing FUCT clothing while walking with their children in a shopping mall.

The court's ruling is posted below:

In Quoting Profanity, Some Judges Give a F#%&. Others Don't

|Marcia Coyle contributed reporting from Washington.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllShaq Signs $11 Million Settlement to Resolve Astrals Investor Claims

5 minute read

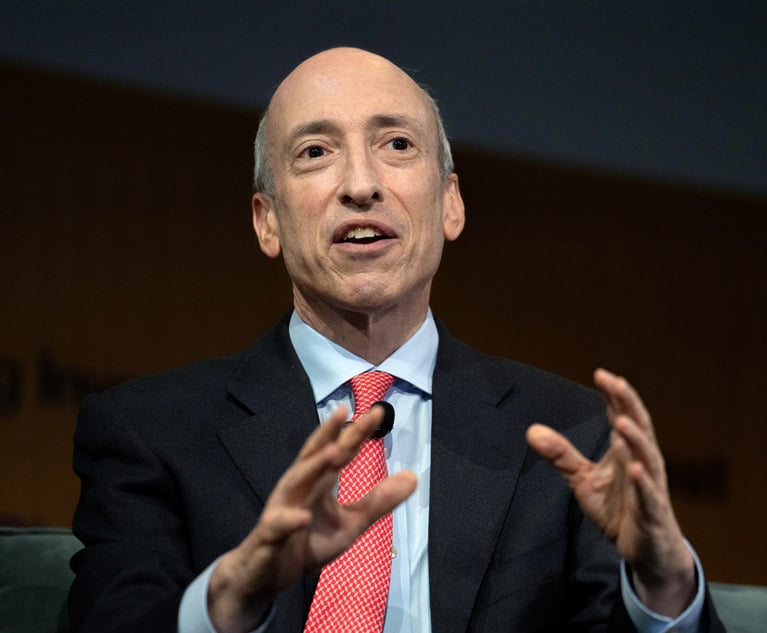

Am Law 100 Partners on Trump’s Short List to Replace Gensler as SEC Chair

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Zero-Dollar Verdict: Which of Florida's Largest Firms Lost?

- 2Appellate Div. Follows Fed Reasoning on Recusal for Legislator-Turned-Judge

- 3SEC Obtained Record $8.2 Billion in Financial Remedies for Fiscal Year 2024, Commission Says

- 4Judiciary Law §487 in 2024

- 5Polsinelli's Revenue and Profits Surge Amid Partner De-Equitizations, Retirements

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250