Dentons' offices in Washington, D.C., at 1900 K Street, N.W., on March 30, 2017. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM

Dentons' offices in Washington, D.C., at 1900 K Street, N.W., on March 30, 2017. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALMDentons Wins $7.4M in Fees, Costs Despite Litigation-Finance Agreement

A U.S. Federal Claims judge's ruling awarded legal fees to Dentons, lead counsel in a patent suit against the U.S. government, despite arguments from the Justice Department that a litigation-funding agreement precluded any award.

July 01, 2019 at 10:44 AM

5 minute read

The global law firm Dentons has won more than $7.4 million in legal fees, expenses and costs for its successful work in a patent suit against the U.S. government, despite having a third-party litigation financing arrangement that Justice Department lawyers said should not have allowed the attorneys to receive any compensation at all.

Dentons successfully sued the government over claims that certain U.S. combat ships violated patents that belonged to the firm's client, FastShip LLC. The law firm, as part of a deal to proceed with the case in the first place, received an initial payment of $600,000 from a Virginia-based entity called IPCo LLC. FastShip ultimately was awarded $12.36 million in damages.

A Washington-based U.S. Court of Federal Claims judge last week rejected the Justice Department's argument that FastShip's legal team, led by Dentons, should be denied attorney fees because of its arrangement with a company that had partially funded the litigation. Judge Charles Lettow awarded $6.2 million in fees and related expenses, and more than $1.2 million in costs.

A Justice Department representative declined to comment Monday. The lead Dentons partner involved in the case was not immediately reached for comment.

Litigation finance arrangements are on the rise, and judges ever more are grappling with novel issues about evidence, legal fees and, more generally, transparency. In his ruling, Lettow described litigation finance as a “controversial,” and evolving, area of the law. The Federal Claims court, the judge noted, “has not yet adopted any rules regarding litigation financing agreements.”

Much of the fee litigation in the Federal Claims court, including the Dentons fee petition itself, and the Justice Department's opposition, remains sealed. Lettow's ruling described the general contours of the dispute, and he included various hourly rates of Dentons partners and associates who worked on the case for FastShip.

The two highest billers for FastShip were Mark Hogge in Washington, chairman of Dentons' legacy patent litigation practice, and Rajesh Noronha, the firm's senior managing associate in Washington. Hogge, the attorney of record for FastShip, charged an average rate of $835, and Noronha charged an average rate of $669, Lettow reported. The firm received an initial payment of $600,000 from the third-party IPCo, which was first registered in 2012.

“Litigation financing agreements help bridge this divide by providing the attorney of record a source of guaranteed fees for their work, while granting the financer a share of the proceeds if the case is successful,” Lettow wrote in his ruling, dated June 27. “Here, IPCo. acted as that bridge, covering the gap between claim and litigation, allowing FastShip to successfully pursue their infringement case. Preventing recovery based on such an agreement would be anathema to the underlying purpose of fee-shifting statutes.”

The Justice Department disputed that FastShip was a real party in interest based on the litigation financing agreement between Dentons and IPCo. The dispute was further complicated by the fact a lawyer for FastShip, Donald Stout of Washington's Fitch Even Tabin & Flannery, was a “'joint member and manager' of IPCo.” Virginia state corporation records show Stout is the registered agent of the company.

“[E]ven if this court had adopted a local rule mandating the disclosure of litigation financing agreements, the court is, and has been, aware of IPCo.'s role in the litigation. As the involvement of Mr. Stout makes evident, at no point was the court in the dark regarding his status,” Lettow said in his ruling.

The judge said “nothing about Mr. Stout's role as a counsel of record and litigation financer suggests that a conflict exists. These two roles are independent of one another and there is no evidence in the record that Mr. Stout acted improperly.”

Stout was not immediately reached for comment Monday.

At one point in his ruling, Lettow examined how litigation-funding practices could be abused, much like the patent system itself. He said he was satisfied “that no double payment or windfall will go to Dentons for any award of attorneys' fees and costs.”

“[T]he possibility of abuse does not mean the entire system should be discarded,” Lettow said. “Instead, courts have focused on the disclosure of such agreements to encourage transparency and ensure a shadow broker is not using litigation as a form of harassment or for multiple bites at the same apple. Disclosure also enables judges to appropriately evaluate potential recusal due to conflicts of interest.”

As Capital Pours In, a Litigation Funding Icon Changes Its Strategy

|David Bario contributed reporting from New York.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllShaq Signs $11 Million Settlement to Resolve Astrals Investor Claims

5 minute read

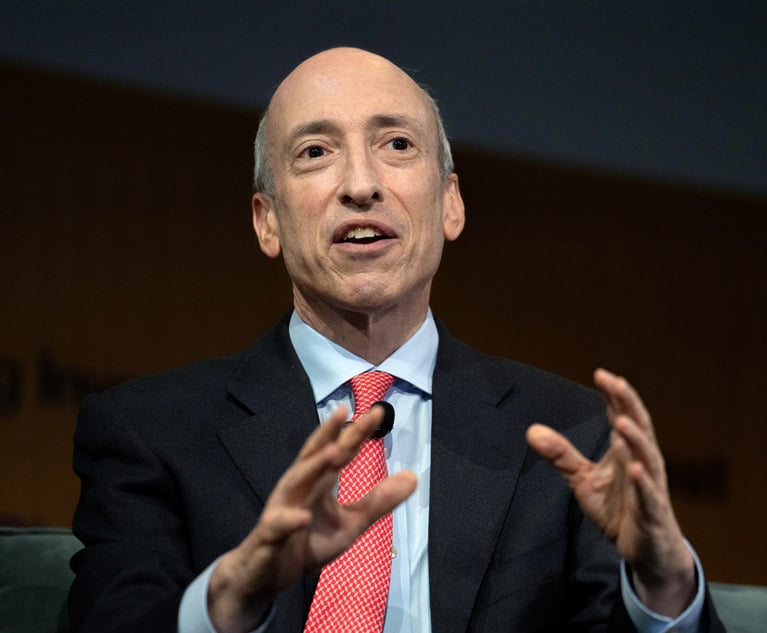

Am Law 100 Partners on Trump’s Short List to Replace Gensler as SEC Chair

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Gibson Dunn Sued By Crypto Client After Lateral Hire Causes Conflict of Interest

- 2Trump's Solicitor General Expected to 'Flip' Prelogar's Positions at Supreme Court

- 3Pharmacy Lawyers See Promise in NY Regulator's Curbs on PBM Industry

- 4Outgoing USPTO Director Kathi Vidal: ‘We All Want the Country to Be in a Better Place’

- 5Supreme Court Will Review Constitutionality Of FCC's Universal Service Fund

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250