Entire Federal Circuit Pleads With Supreme Court, Congress on Diagnostics Patents

Flawed precedent is making it impossible to patent often life-saving medical discoveries, all 12 active judges say in flurry of opinions.

July 08, 2019 at 12:39 PM

6 minute read

Top, left to right: Alan Lourie, Timothy Dyk and Todd Hughes. Bottom, left to right: Kimberly Moore, Pauline Newman and Kara Stoll.

Top, left to right: Alan Lourie, Timothy Dyk and Todd Hughes. Bottom, left to right: Kimberly Moore, Pauline Newman and Kara Stoll.Unanimity is rare at the famously factious U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. But all 12 active judges found something they could agree on Wednesday: The Supreme Court is flat-out wrong when it comes to patent eligibility and medical diagnostics.

But in Federal Circuit fashion, the judges could not agree among themselves on just how wrong the Supreme Court is. The D.C.-based appellate court—which has the last word on patent law short of the Supreme Court—produced eight separate opinions Wednesday in Athena Diagnostics v. Mayo Collaborative Services. Five judges said the Federal Circuit must find a way to make expensive, often life-saving diagnostics eligible for patenting under the Supreme Court's framework. But the majority concluded that the Supreme Court has simply made that impossible. Remarkably, all 12 implored the justices—or Congress—to fix the problem.

At issue is U.S. Patent 7,267,820 held by Oxford University and the Max Planck Society and licensed to Quest Diagnostics Inc. subsidiary Athena Diagnostics Inc. The inventors discovered that antibodies to a protein called muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) are correlated with neurological disorders such as myasthenia gravis. The Mayo Clinic developed a competing test that Athena accuses of infringing.

A divided three-judge panel ruled in February that it was compelled by the Supreme Court's 2012 decision Prometheus Laboratories v. Mayo Collaborative Services to find the patent ineligible. Mayo is the second of four Supreme Court decisions in the last decade that have expanded the judicial exceptions to statutory patent eligibility, leading to pushback from inventors, bio-pharma companies and, this year, a vocal handful of senators and House members.

On Wednesday, seven judges reluctantly agreed with the three-judge panel, while joining the chorus for reconsidering Mayo or amending Section 101. Even Judge Timothy Dyk, usually one of the most hawkish members of the court on eligibility, wrote separately to argue that the high court should leave room for precisely claimed diagnostic patents.

“Because at least some of the claims here recite specific applications of the newly discovered law of nature with proven utility, this case could provide the Supreme Court with the opportunity to refine the Mayo framework as to diagnostic patents,” Dyk wrote.

Judges Todd Hughes and Raymond Chen joined much of Dyk's opinion.

Judge Alan Lourie wrote in a similar vein. His preference would be excluding only claims that are directed to a natural law itself, such as an attempt to patent the mathematical formula e=mc2. The use or detection of natural laws such as those asserted by Athena ought to be patentable, he suggested. “But we do not write here on a clean slate; we are bound by Supreme Court precedent,” he wrote.

Judge Jimmie Reyna and Chen joined Lourie's opinion.

Judge Hughes wrote that while the court is bound by Mayo, he would welcome further development of the law by the Supreme Court or Congress. The goal would be “providing a reasonable and measured way to differentiate between overly broad patents claiming natural laws and truly worthy specific applications.”

Chief Judge Sharon Prost and Judge Richard Taranto concurred in Hughes' opinion.

Chen wrote separately to argue that Mayo is out of step with other Supreme Court eligibility opinions, 1981's Diamond v. Diehr and 2013's Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics. While it's tempting to read all three together and find an exception for diagnostics, “it is not an inferior court's role to dodge the clear, recent direction of the Supreme Court,” Chen concluded.

Judge Kimberly Moore began her dissent from denial of en banc review by noting that every judge agreed some of the claims at issue in Athena should be eligible. “The only difference among us is whether the Supreme Court's Mayo decision requires this outcome.”

She argued the Supreme Court did not intend Mayo to be the “sweeping” decision her colleagues see it as. By refusing to grant en banc review, “We have turned Mayo into a per se rule that diagnostic kits and techniques are ineligible,” she wrote. “The Supreme Court has repeatedly cautioned against rigid or per se rules.”

Moore noted that at recent hearings of the Senate Judiciary's IP subcommittee, Sen. Chris Coons has similarly complained that “for medical diagnostics, … [there is] a presumption against eligibility that is nearly impossible to overcome.”

Mayo and the Federal Circuit cases interpreting it have excluded breakthrough discoveries for diagnosing breast cancer, tuberculosis and fetal abnormalities unpatentable, Moore wrote. “It is these life-saving fields though, with such high costs to the initial market investor, where patent protection is critical,” she wrote.

Finally, Moore spoke directly to the biotech industry. “No need to waste resources with additional en banc requests. Your only hope lies with the Supreme Court or Congress,” she wrote. “I hope that they recognize the importance of these technologies, the benefits to society, and the market incentives for American business. And, oh yes, that the statute clearly permits the eligibility of such inventions and that no judicially created exception should have such a vast embrace.”

Judges Kathleen O'Malley, Evan Wallach and Kara Stoll concurred in Moore's opinion.

Judge Pauline Newman also dissented separately to argue that Athena's diagnostic method is not a law of nature. “It is a novel man-made method of diagnosis of a neurological disorder,” she wrote. Judge Evan Wallach concurred with Newman.

Stoll also sounded alarms in another dissent. She accused her colleagues of fashioning Mayo into “an over-reaching and flawed test for eligibility, a test that undermines the constitutional rationale for having a patent system—promoting the progress of science and useful arts.” Wallach concurred in Stoll's opinion.

Finally, O'Malley questioned the legitimacy of the Supreme Court's eligibility jurisprudence and seemed to suggest that her colleagues defy it.

She argued that the Mayo decision's addition of “an inventive concept” requirement directly contradicts congressional action to remove “inventiveness” from Section 101 in 1952. “Had the Supreme Court not disregarded Congress's wishes for a second time, perhaps the outcome in this case would be different,” she wrote.

“Because the Supreme Court judicially revived the invention requirement and continues to apply it despite express abrogation, I dissent to encourage Congress to clarify that there should be no such requirement read into Section 101,” O'Malley wrote.

Wedensday's decision denying en banc review preserved a win for a Fish & Richardson team led by partner Jonathan Singer that represented the Mayo Clinic. Fenwick & West, White & Case and Robins Kaplan represent the patent owners and licensees.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Hogan Lovells, Jenner & Block Challenge Trump EOs Impacting Gender-Affirming Care

3 minute read

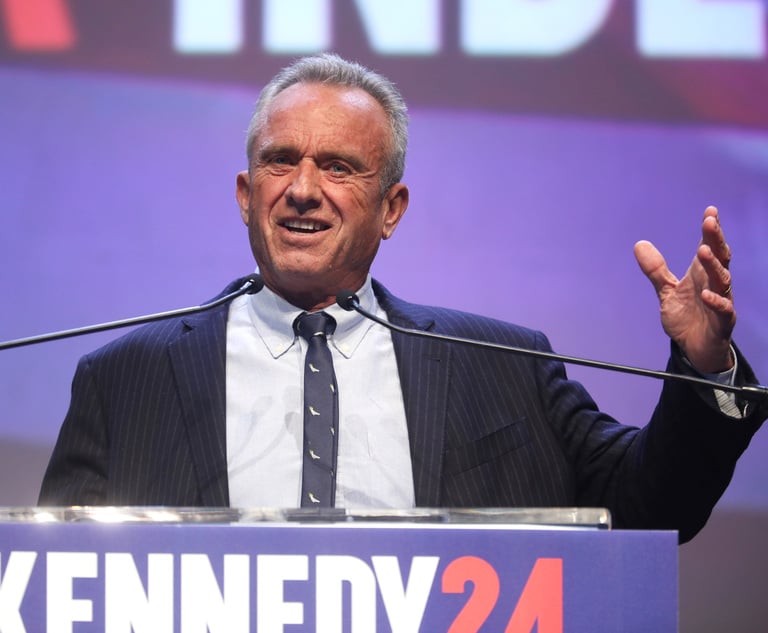

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

'Religious Discrimination'?: 4th Circuit Revives Challenge to Employer Vaccine Mandate

2 minute read

'Pull Back the Curtain': Ex-NFL Players Seek Discovery in Lawsuit Over League's Disability Plan

Trending Stories

- 1States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 2Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 3Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 4Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

- 5Securities Report Says That 2024 Settlements Passed a Total of $5.2B

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250